Take, for instance, the word 'diet'. It's one of the most hated words. There are several meanings, but the most popular seems to be understood as 'an habitual way of eating'. Viewing it this way can, and has, led to thoughts of having to restrict what we eat, but the word's original definition, according to the Oxford dictionary, means 'way of life'. If we view it as a lifestyle, perhaps it won't feel as oppressive.

The word 'obesity' is a good example of how language can change abruptly. Don't think this can happen? Back in 1998, with the adoption of the Body Mass Index (BMI), it did. The National Institute of Heath (NIH), the primary governmental health related and biomedical research agency, made changes to the definition of this word that affected 25 million Americans who, under the old guidelines were considered of average weight, but who suddenly became obese. What's interesting is that just prior to that change:

The American Heart Association recently added obesity to its list of major risk factors for heart disease and heart attack, along with smoking, high blood pressure, high cholesterol and a sedentary lifestyle.From that moment on, not only was a percentage of the population suddenly classified as obese, but they were now considered at risk from other diseases. Was all of this just the result of good intentions gone awry?

What is BMI?

In short, it's the calculation of a person's weight and height in order to determine whether they are obese, according to government standards. BMI stands for body mass index and was developed by Lambert Adolphe Jacques Quetelet, a 19th century Belgian mathematician. He produced this formula to give the government a quick and easy way to measure obesity in the general population in order to allocate resources. So not only was he not a physician, but it's a formula that wasn't supposed to apply to the amount of fat on an individual. You can find more reasons why BMI doesn't add up here and here.

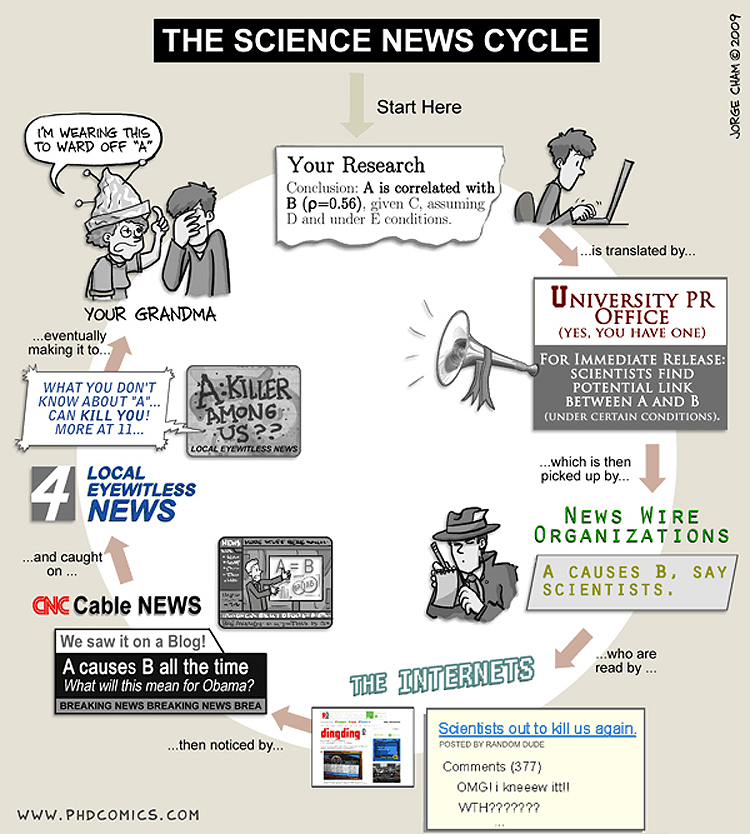

The bottom line (no pun intended) is that these guidelines, that have so many people stressed and feeling guilty, are basically meaningless. As a result of these guidelines, a person falling under the 'obese' label may unknowingly be healthy and a thin and 'health nut' may be at risk of disease. In this case, it seems the government used information unverified by sound scientific research to push an agenda, and the media ran with it. How does something so egregiously wrong happen?

The Chasm Between Science, the Public and the Media Who Refuse to Act on their Behalf

Abigail C. Saguy and Rene Almeling, authors of Fat in the Fire? Science, the News Media, and the ''Obesity Epidemic'' published a study that showed that the more dramatic the title of an article and the content of the article itself, the greater the public response would be. While I agree that a more sensationalistic slant can draw one's attention, I also wonder if the reason for this disconnect lies with the usage of scientific language which in many respects is foreign to the layperson. That may be one factor in loss of public interest in the more scientific articles. However, if one did happen to understand an abstract from a paper and desired to learn more, the cost for access to such articles would quickly add up.

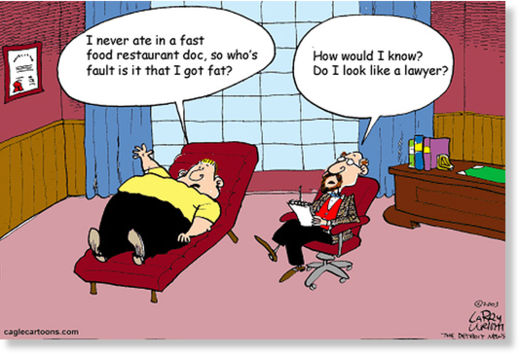

For those who have difficulty with scientific literature, you may ask, why don't scientists publish their findings in layman's language? Here's a humorous exchange that attempts to answer the question:

First person: Imagine you're playing Starcraft II, almost done the single player campaign. You want to discuss strategies with your friends on the last mission - how to approach it, what to focus on, etc.

Now imagine you're trying to explain to someone completely new to the game (e.g., your mother) why facing Nydus worms is preferable over Brood Lords. You'll be spending most of your time explaining the basics, or even the story, before you get to the good part.

Most scientists simply cannot write a thorough explanation of the basics before introducing their findings, while keeping the article a reasonable length.

Second person: Wow... that was a layman explanation of layman explanations... but it really got the point across well.

First person: Wait a minute, are you saying I just did successfully what I'm trying to say can't be done easily?This may be a simplistic representation of one of the issues but is an interesting idea nonetheless. The lack of importance placed on learning science and math in particular definitely comes into play here. This results in the loss of much needed knowledge that keeps the masses ignorant. If we don't understand what we are reading, the ability to discern between truth and lies is greatly hampered and we tend to believe whatever we are told. This leaves a lot of scope for the scientific community, straddled as it is by Big Industry, and the media, to present information based on their self interest, which few will question:

Uh... I'll show myself out.

These findings support the contention that scientists work as ''para-journalists'' (Schudson, 2003) 1, writing up their studies - especially the abstract - with journalists in mind. They then frame their research via press releases and interviews with journalists. A reward structure in which, all things being equal, alarmist studies are more likely to be covered in the media may make scientists even more prone to presenting their findings in the most dramatic light possible. Do journalists, in turn, function as ''parascientists''? No, if the definition of a parascientist involves independently evaluating research studies.We already know how the tobacco issue is turning out. Will it be the same for obesity? Once the program is in place, research is no longer needed because everyone has placed their trust in information that's not even wrong. Here's what Dr. Jeffrey Friedman, an obesity researcher, has to say in his article, A War on Obesity Not the Obese:

However, journalists can raise questions about research by citing skeptical ''experts'' or shape public understandings of the scientific field by featuring some pieces of research while ignoring others.2 We found ample evidence that the news media report more on some studies than on others, but little evidence of the news media expressing skepticism of the research on which they were reporting, either directly or via new sources. Future work should examine when such skepticism is more likely. We would expect this to be the case when the research flies in the face of received wisdom or when an alternative view has crossed a tipping point - either with the individual journalist or for a perceived readership - in which it becomes an obligatory reference. Related to this, future work should also examine how the news media report on conflicting or competing findings by scientists. Which kinds of claims, findings, or scientists are given most credibility by the news media and how is such credibility conveyed?

In that how public issues are framed shapes private and public action, the patterns that we have documented have far-reaching social implications. As obesity is widely accepted as a dire health risk, we may become more tolerant of health risks associated with weight-loss treatments, enact public policies designed to promote weight loss on a population level, and prioritize funding for obesity research over competing causes. Indeed, in recent years, funds for tobacco research have declined as funds for obesity research climb (Saguy, 2006).

Alarm about the health crisis associated with an emerging "obesity epidemic" is sounded almost weekly in response to reports that its incidence has greatly increased over the past decade. Many argue that this explosive increase over a short period of time indicates that the obesity problem is primarily a result of our modern lifestyle. The facts, however, do not support this conclusion. For example this argument fails to take into account that the increasing incidence of obesity in the population, from 23.3 percent in 1991 to 30.9 percent today, is not reflected by a proportionate increase in the weight of the average American, which grew by just 7 to 10 pounds.While Friedman does admit that, with certain individuals, there is an increase in weight, as it is with other wars, this 'war' also appears to be something of a racket.

Going back to Saguy and Almeling, they suggest that both science and media tend to blame the individual more than social structure or genetic factors. They also state that being a member of certain groups (eg. children, ethnic minorities) increases the chance of being blamed as the sole cause. In the case of children, what is usually implied is that the parents - particularly mothers - are at fault.

Below is one of a few ads by a group called Strong4Life of the Children's Healthcare of Atlanta (CHOA) that attempts to raise awareness about childhood obesity. I'll leave you to form your own opinion:

Creating an obesity panic helps no one except those who profit financially from it. What's even sadder is that as people scramble to get to their local 'Whole Foods' or other 'health store', they're still being led astray. If those foods are so beneficial, why do people seem to be getting sicker than ever? Something is very, very wrong. Could it be that, in the same way the war on obesity is based on information skewed to protect the interests of corporations, the information provided by governments about diet is equally skewed?

There is no easy answer to the question of why people are different shapes and sizes, but one thing we can do, if we choose, is to start taking responsibility for our own health and well being. Not because someone tells us to, or makes us feel guilty about it, but because we care enough about ourselves enough to do our own research. Where to start? First and foremost we need to look beyond the information provided to us by the mainstream media. Secondly, we need to check for ourselves by testing what foods work and don't work for us. In the links in the comment box at the end of this article, you'll find information that has benefited many people. The foods that have been shown by impartial scientific research to cause most problems are: gluten, dairy, sugar, corn and soy. Just by removing gluten and dairy alone, you'll notice a vast improvement in your health. Because at the end of the day, that's what really matters. It's not how you look, but how you feel, that counts.

Sources:

- Schudson, Michael. 2003

Let me start by saying I am one of the fortunate who has never had an obesity problem although at times in my life I realized that my weight was moving toward the fat. Just last night I watched a Dr. Oz show which made bariatric surgery look like a dream come true for anyone overweight and diabetic. My skepticism made me question the sanity of this approach - permanently modify your digestive system by creating a new pocket for a stomach and close off the rest of the stomach, reroute the food to the small intestine. This again sounded so much like what a mechanic would say if your car had a rattle in the door - cut the door off and throw it away - problem solved - no more door - but now you will be subjected to all kinds of noise that was previously blocked by the door.

Is this push for bariatric surgery just another scheme to extract more billions from the consumers of health care in this country? Don't we already spend several times what the rest of the civilized world spends on healthcare already, how can afford to support billions in elective surgery to eliminate the "disease" of obesity and cure type 2 diabetes? It seems like a clumsy attempt to further muddy the healthcare waters with elective procedures which on the surface seem miraculous yet at their heart are just crude mechanical solutions practiced on a organism as elegant as the human body.

Instead of looking a obesity as something that has been created by the processed and fast food industries, we label it as a "disease" and now we can add it to the growing list of treatable symptoms. Is there no end to this manipulation and plundering of the resources of this country. Instead of using resources to create a better and more meaningful society raising peoples standard of living and happiness, we are being herded into the healthcare stockyard for slaughter, for the benefit of the corporations and a few psychopathic CEOs.

If we spent a fraction of the energy devoted to describing the "disease" of obesity, looking at the real reasons behind the epidemic, we might begin to see behind a part of the curtain to understand just what is being foisted on the people of this planet. We might also realize that first and foremost we need to embrace our responsibility for ourselves and this disaster that we call a health care system in this country, an anathema in the modern world.