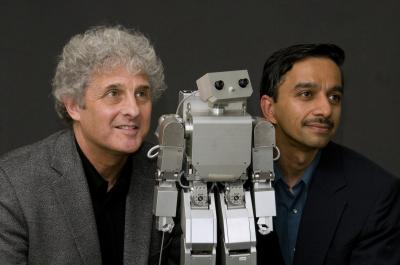

© University of WashingtonMorphy the robot

University of Washington researchers are studying what makes babies decide the difference between sentient and inanimate objects, and also

how they interact and learn from these objects, such as robots.

Babies are curious and interested in almost everything their parents do. They learn and socialize by mimicking an adult's actions. For instance, if an adult touches their nose to teach the baby where their nose is, the baby will learn to touch their nose as well when asked where it is.

Andrew Meltzoff, lead author of the study and co-director of of the University of Washington's Institute for Learning and Brain Sciences; Rechele Brooks, co-author of the study and a UW research assistant professor; and Rajesh Rao, co-author and UW associate professor of computer science and engineering, have studied babies' interactions with adults and inanimate objects in an effort to understand how they perceive and learn from different "teachers."

"Babies learn best through social interactions, but what makes something 'social' for a baby?" said Meltzoff. "

It is not just what something looks like, but how it moves and interacts with others that gives it special meaning to the baby."

To further investigate this question, 64 babies were used in the study to observe certain interactions. All were around the age of 18-months-old, and were allowed to play with toys for awhile in order to become comfortable with the experimental setting. Once the babies were adjusted to this setting, Brooks brought out a "metallic

humanoid robot" with a torso, legs, arms, head and eyes that were actually camera lenses. The robots name was Morphy, and was controlled by a researcher who was hidden from the babies' view.

Brooks then followed a script where she interacted with Morphy, asking the robot questions like "Where is your tummy?" and "Where is your head?" Morphy would then act accordingly, pointing to its head and tummy.

After 90 minutes of interaction, Brooks left the room while Morphy continued to "move on its own," and researchers measured if the babies thought Morphy was real or not. Morphy continued to make subtle movements and sounds to hold the babies' attention, and results showed that 13 out of 16 babies would follow Morphy's gaze when it would look at a nearby toy or make a subtle movement. For the control group of babies who did not witness Brooks playing with the robot first, only three out of 16 babies followed the Morphy's movements.

"We are using modern technology to explore an age-old question about the essence of being human," said Meltzoff. "The babies are telling us that

communication with other people is a fundamental feature of being human."

This study was published in

Neural Networks.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter