The bailout plan is more than just a giveaway to the rich as represented by the big banks (although it is that). It probably is a panicked attempt to forestall the real potential crisis: a collapse of the huge, unregulated hedge funds based on derivatives and Credit Default Swaps (CDS).

-------

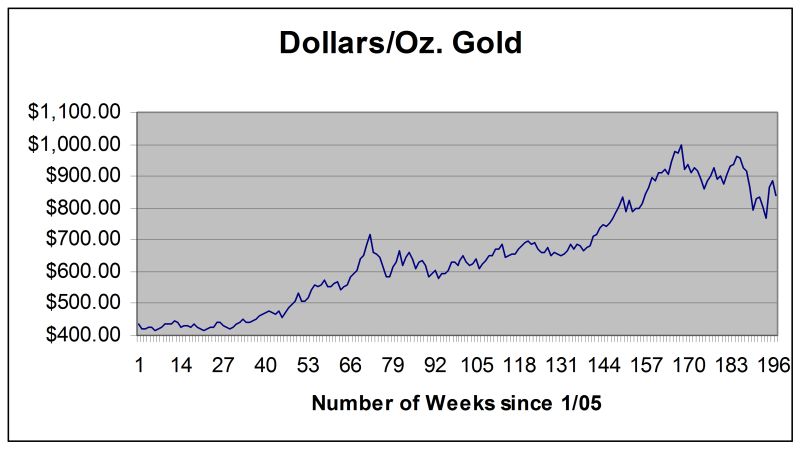

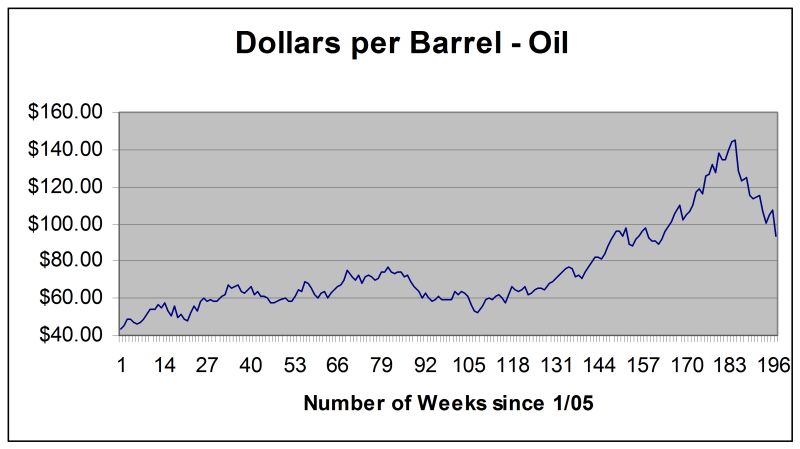

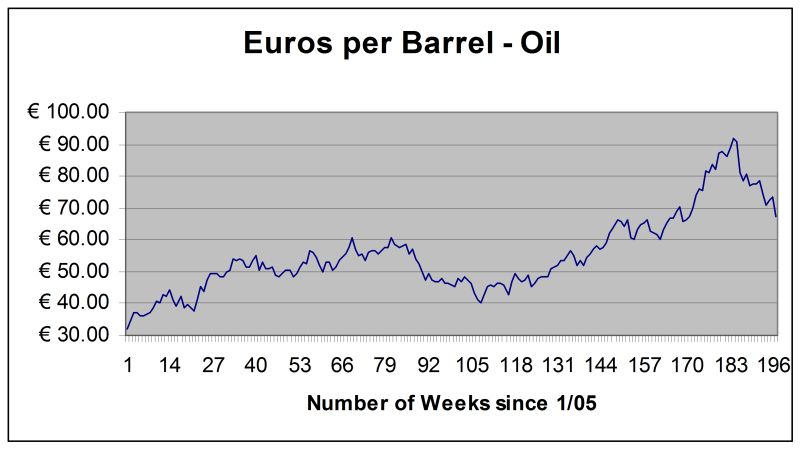

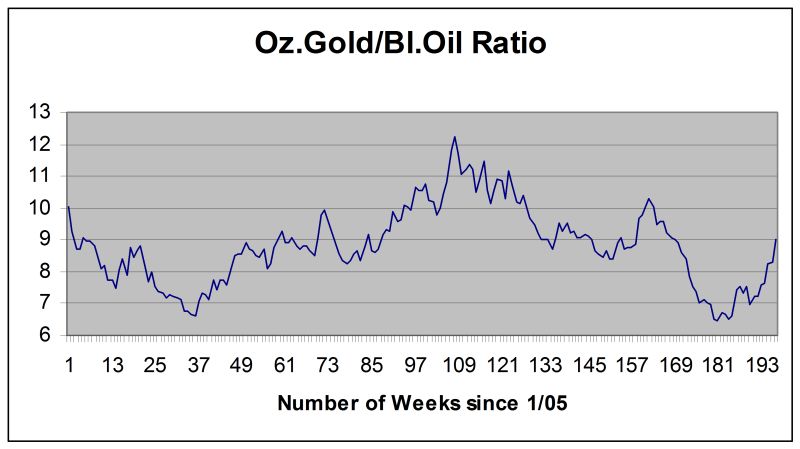

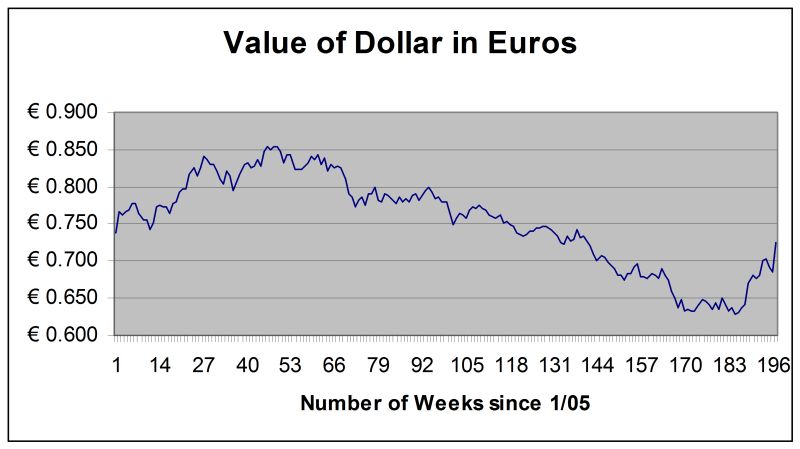

Gold closed at 840.80 dollars an ounce Friday, down 5.6% from $887.90 for the week. The dollar closed at 0.7255 euros Friday, up 6.0% from 0.6845 at the close of the previous week. That put the euro at 1.3783 dollars compared to 1.4609 the week before. Gold in euros would be 610.03 euros an ounce, up 0.4% from 607.78 at the close of the previous week. Oil closed at 93.10 dollars a barrel Friday, down 15.2% from 107.26 at the end of the week before. Oil in euros would be 67.55 euros a barrel, down 8.7% from 73.42 for the week. The gold/oil ratio closed at 9.03 Friday, up 9.1% from 8.28 at the close of the previous week. In U.S. stocks, the Dow closed at 10,325.38 Friday, down 7.9% from 11,140.26 at the close of the previous Friday. The NASDAQ closed at 1,947.39 Friday, down 12.1% from 2,183.34 for the week. In U.S. interest rates, the yield on the ten-year U.S. Treasury note closed at 3.60%, down 24 basis points from 3.84 at the close of the week before.

The past week was the last of the third quarter of 2008, so let's look at the quarterly and year-to-date numbers. Gold fell 10.8% from $931.30 for the quarter and fell 0.2% from $842.70 for the year. The dollar rose 14.6% from 0.6332 for the quarter and rose 6.8% from 0.6795 for the year. Gold in euros rose 3.4% from 589.69 for the quarter and rose 6.5% from 572.64 for the year. Oil fell 50.6% from 140.21 for the quarter and fell 3.3% from 96.16 for the year. Oil in euros fell 31.4% from €88.78 for the quarter and rose 3.4% from €65.34 for the year. The gold/oil ratio rose 36.0% from 6.64 for the quarter and rose 3.1% from 8.76 for the year. In U.S. stocks, the Dow fell 10.0% from 11,346.51 for the quarter and fell 29.4% from 13,365.87 for the year. The NASDAQ fell 18.8% from 2,315.63 for the quarter and fell 37.3% from 2,674.46 for the year. The yield on the ten-year T-Note fell 37 basis points from 3.97 for the quarter and 47 basis points from 4.07 for the year.

Gold and oil were pretty much unchanged for the year but dropped sharply in the third quarter. The dollar strengthened significantly against the euro this year and U.S. stocks suffered significant losses.

The big financial bailout plan finally passed in the U.S. Congress Friday over the strong objections of the public. Will the bailout prevent the coming depression? Probably not. As Paul Craig Roberts explains, mortgage securities are only a part of the problem:

Why Paulson's Plan is a FraudThe bailout plan is more than just a giveaway to the rich as represented by the big banks (although it is that). It probably is a panicked attempt to forestall the real potential crisis: a collapse of the huge, unregulated hedge funds based on derivatives and Credit Default Swaps (CDS). What are CDSs? The following article explains:

Bail Out the Homeowners!

By Paul Craig Roberts

Counterpunch.org

October 3 - 5, 2008

Is the Paulson bailout itself as big a fraud as the leveraged subprime mortgages?

Yesterday, here on CounterPunch, I discussed the bailout as proposed and noted that the proposal cannot succeed if it impairs the US Treasury's credit standing and/or the combination of mark-to-market and short-selling permits short-sellers to prosper by driving more financial institutions into bankruptcy.

A reader's comment and an article by Yale professors Jonathan Kopell and William Goetzmann raise precisely this question of the fraudulence of the Paulson package.

As one reader put it, "We have debt at three different levels: personal household debt, financial sector debt and public debt. The first has swamped the second and now the second is being made to swamp the third. The attitude of our leaders is to do nothing about the first level of debt and to pretend that the third level of debt doesn't matter at all."

The argument for the bailout is that the banks will be free of the troubled instruments and can resume lending and that the US Treasury will recover most of the bailout costs, because only a small percentage of the underlying mortgages are bad. Let's examine this argument.

In actual fact, the Paulson bailout does not address the core problem. It only addresses the problem for the financial institutions that hold the troubled assets. Under the bailout plan, the troubled assets move from the banks' books to the Treasury's. But the underlying problem--the continuing diminishment of mortgage and home values--remains and continues to worsen.

The origin of the crisis is at the homeowner level. Homeowners are defaulting on mortgages. Moving the financial instruments onto the Treasury's books does not stop the rising default rate.

The bailout is focused on the wrong end of the problem. The bailout should be focused on the origin of the problem, the defaulting homeowners. The bailout should indemnify defaulting homeowners and pay off the delinquent mortgages. As Koppell and Goetzmann point out, the financial instruments are troubled because of mortgage defaults. Stopping the problem at its origin would restore the value of the mortgage-based derivatives and put an end to the crisis.

This approach has the further advantage of stopping the slide in housing prices and ending the erosion of local tax bases that result from foreclosures and houses being dumped on the market. What about the moral hazard of bailing out homeowners who over-leveraged themselves? Ask yourself: How does it differ from the moral hazard of bailing out the financial institutions that securitized questionable loans, insured them, and sold them as investment grade securities? Congress should focus the bailout on refinancing the troubled mortgages as the Home Owners' Loan Corp. did in the 1930s, not on the troubled institutions holding the troubled instruments linked to the mortgages. Congress needs to back off, hold hearings, and talk with Koppell and Goetzmann.Congress must know the facts prior to taking action. The last thing Congress needs to do is to be panicked again into agreeing to a disastrous course.

The $55 trillion questionFriday's release of the September job numbers for the U.S. showed that this is no longer just a financial crisis, that the real economy is suffering as well:

The financial crisis has put a spotlight on the obscure world of credit default swaps - which trade in a vast, unregulated market that most people haven't heard of and even fewer understand. Will this be the next disaster?

Nicholas Varchaver and Katie Benner

Fortune Magazine

September 30, 2008

As Congress wrestles with another bailout bill to try to contain the financial contagion, there's a potential killer bug out there whose next movement can't be predicted: the Credit Default Swap.

In just over a decade these privately traded derivatives contracts have ballooned from nothing into a $54.6 trillion market. CDS are the fastest-growing major type of financial derivatives. More important, they've played a critical role in the unfolding financial crisis. First, by ostensibly providing "insurance" on risky mortgage bonds, they encouraged and enabled reckless behavior during the housing bubble.

"If CDS had been taken out of play, companies would've said, 'I can't get this [risk] off my books,'" says Michael Greenberger, a University of Maryland law professor and former director of trading and markets at the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. "If they couldn't keep passing the risk down the line, those guys would've been stopped in their tracks. The ultimate assurance for issuing all this stuff was, 'It's insured.'"

Second, terror at the potential for a financial Ebola virus radiating out from a failing institution and infecting dozens or hundreds of other companies - all linked to one another by CDS and other instruments - was a major reason that regulators stepped in to bail out Bear Stearns and buy out AIG, whose calamitous descent itself was triggered by losses on its CDS contracts.

And the fear of a CDS catastrophe still haunts the markets. For starters, nobody knows how federal intervention might ripple through this chain of contracts. And meanwhile, as we'll see, two fundamental aspects of the CDS market - that it is unregulated, and that almost nothing is disclosed publicly - may be about to change. That adds even more uncertainty to the equation.

"The big problem is that here are all these public companies - banks and corporations - and no one really knows what exposure they've got from the CDS contracts," says Frank Partnoy, a law professor at the University of San Diego and former Morgan Stanley derivatives salesman who has been writing about the dangers of CDS and their ilk for a decade. "The really scary part is that we don't have a clue." Chris Wolf, a co-manager of Cogo Wolf, a hedge fund of funds, compares them to one of the great mysteries of astrophysics: "This has become essentially the dark matter of the financial universe."

At first glance, credit default swaps don't look all that scary. A CDS is just a contract: The "buyer" plunks down something that resembles a premium, and the "seller" agrees to make a specific payment if a particular event, such as a bond default, occurs. Used soberly, CDS offer concrete benefits: If you're holding bonds and you're worried that the issuer won't be able to pay, buying CDS should cover your loss. "CDS serve a very useful function of allowing financial markets to efficiently transfer credit risk," argues Sunil Hirani, the CEO of Creditex, one of a handful of marketplaces that trade the contracts.

Because they're contracts rather than securities or insurance, CDS are easy to create: Often deals are done in a one-minute phone conversation or an instant message. Many technical aspects of CDS, such as the typical five-year term, have been standardized by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA). That only accelerates the process. You strike your deal, fill out some forms, and you've got yourself a $5 million - or a $100 million - contract.

And as long as someone is willing to take the other side of the proposition, a CDS can cover just about anything, making it the Wall Street equivalent of those notorious Lloyds of London policies covering Liberace's hands and other esoterica. It has even become possible to purchase a CDS that would pay out if the U.S. government defaults. (Trust us when we say that if the government goes under, trying to collect will be the least of your worries.)

You can guess how Wall Street cowboys responded to the opportunity to make deals that (1) can be struck in a minute, (2) require little or no cash upfront, and (3) can cover anything. Yee-haw! You can almost picture Slim Pickens in Dr. Strangelove climbing onto the H-bomb before it's released from the B-52. And indeed, the volume of CDS has exploded with nuclear force, nearly doubling every year since 2001 to reach a recent peak of $62 trillion at the end of 2007, before receding to $54.6 trillion as of June 30, according to ISDA.

Take that gargantuan number with a grain of salt. It refers to the face value of all outstanding contracts. But many players in the market hold offsetting positions. So if, in theory, every entity that owns CDS had to settle its contracts tomorrow and "netted" all its positions against each other, a much smaller amount of money would change hands. But even a tiny fraction of that $54.6 trillion would still be a daunting sum.

The credit freeze and then the Bear disaster explain the drop in outstanding CDS contracts during the first half of the year - and the market has only worsened since. CDS contracts on widely held debt, such as General Motors', continue to be actively bought and sold. But traders say almost no new contracts are being written on any but the most liquid debt issues right now, in part because nobody wants to put money at risk and because nobody knows what Washington will do and how that will affect the market. ("There's nothing to do but watch Bernanke on TV," one trader told Fortune during the week when the Fed chairman was going before Congress to push the mortgage bailout.) So, after nearly a decade of exponential growth, the CDS market is poised for its first sustained contraction.

One reason the market took off is that you don't have to own a bond to buy a CDS on it - anyone can place a bet on whether a bond will fail. Indeed the majority of CDS now consists of bets on other people's debt. That's why it's possible for the market to be so big: The $54.6 trillion in CDS contracts completely dwarfs total corporate debt, which the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association puts at $6.2 trillion, and the $10 trillion it counts in all forms of asset-backed debt.

"It's sort of like I think you're a bad driver and you're going to crash your car," says Greenberger, formerly of the CFTC. "So I go to an insurance company and get collision insurance on your car because I think it'll crash and I'll collect on it." That's precisely what the biggest winners in the subprime debacle did. Hedge fund star John Paulson of Paulson & Co., for example, made $15 billion in 2007, largely by using CDS to bet that other investors' subprime mortgage bonds would default.

So what started out as a vehicle for hedging ended up giving investors a cheap, easy way to wager on almost any event in the credit markets. In effect, credit default swaps became the world's largest casino. As Christopher Whalen, a managing director of Institutional Risk Analytics, observes, "To be generous, you could call it an unregulated, uncapitalized insurance market. But really, you would call it a gaming contract."

There is at least one key difference between casino gambling and CDS trading: Gambling has strict government regulation. The federal government has long shied away from any oversight of CDS. The CFTC floated the idea of taking an oversight role in the late '90s, only to find itself opposed by Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan and others. Then, in 2000, Congress, with the support of Greenspan and Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers, passed a bill prohibiting all federal and most state regulation of CDS and other derivatives. In a press release at the time, co-sponsor Senator Phil Gramm - most recently in the news when he stepped down as John McCain's campaign co-chair this summer after calling people who talk about a recession "whiners" - crowed that the new law "protects financial institutions from over-regulation ... and it guarantees that the United States will maintain its global dominance of financial markets." (The authors of the legislation were so bent on warding off regulation that they had the bill specify that it would "supersede and preempt the application of any state or local law that prohibits gaming ...") Not everyone was as sanguine as Gramm. In 2003 Warren Buffett famously called derivatives "financial weapons of mass destruction."

There's another big difference between trading CDS and casino gambling. When you put $10 on black 22, you're pretty sure the casino will pay off if you win. The CDS market offers no such assurance. One reason the market grew so quickly was that hedge funds poured in, sensing easy money. And not just big, well-established hedge funds but a lot of upstarts. So in some cases, giant financial institutions were counting on collecting money from institutions only slightly more solvent than your average minimart. The danger, of course, is that if a hedge fund suddenly has to pay off on a lot of CDS, it will simply go out of business. "People have been insuring risks that they can't insure," says Peter Schiff, the president of Euro Pacific Capital and author of Crash Proof, which predicted doom for Fannie and Freddie, among other things. "Let's say you're writing fire insurance policies, and every time you get the [premium], you spend it. You just assume that no houses are going to burn down. And all of a sudden there's a huge fire and they all burn down. What do you do? You just close up shop."

This is not an academic concern. Wachovia and Citigroup are wrangling in court with a $50 million hedge fund located in the Channel Islands. The reason: A dispute over two $10 million credit default swaps covering some CDOs. The specifics of the spat aren't important. What's most revealing is that these massive banks put their faith in a Lilliputian fund (in an inaccessible jurisdiction) that was risking 40% of its capital for just two CDS. Can anyone imagine that Citi would, say, insure its headquarters building with a thinly capitalized, unregulated, offshore entity?

That's one element of what's known as "counterparty risk." Here's another: In many cases, you don't even know who has the other side of your bet. Parties to the contract can, and do, transfer their side of the contract to third parties. Investment firms assert that transfers are well documented (a claim that, like most in the world of CDS, is impossible to verify). But even if that's true, you're still left with the fact that a given company's risks are being dispersed in ways that they may not know about and can't control.

It doesn't help that CDS trading is a haphazard process. Most contracts are bought and sold over the phone or by instant message and settled manually. Settlement has been sloppy, confirms Jamie Cawley of IDX Capital, a firm that brokers trades between big banks. Pushed by New York Fed president Timothy Geithner, the players have been improving the process. But even as recently as a year ago, Cawley says, so many trades were sitting around unfulfilled that "there were $1 trillion worth of swaps that were unsettled among counterparties."

Trade settlement is not the only anachronistic aspect of CDS trading. Consider what will happen with CDS contracts relating to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The two were placed in conservatorship on Sept. 7. But the value of many contracts won't be determined till Oct. 6, when an auction will set a cash price for Fannie and Freddie bonds. We'll spare you the technical reasons, but suffice it to ask: Can you imagine any other major market that would need a month to resolve something like this?...

159,000 drop in US payrolls signals deepening recessionAs Barry Grey noted in the previous article the financial crisis is no longer limited to the United States. The crisis is spreading rapidly in Europe. Even Germany, home to the most conservative banking and financial practices, is not immune:

GM to close Ohio plant by year's end

Barry Grey

WSWS.org

4 October 2008

The US Labor Department on Friday reported a net loss of 159,000 non-farm jobs in September, as payrolls shrank in virtually every sector of the private economy. The jobless survey, considerably worse than forecast by economists, reflected the gathering strength of a recession that is global in scope and is poised to worsen.

The government report, based on a survey conducted prior to the collapse of credit markets in the wake of the September 15 bankruptcy filing of Lehman Brothers, does not fully account for the impact of the widening financial crisis on the broader economy. Many economists predict that layoffs will accelerate in the coming weeks, with the official unemployment rate rising from the current 6.1 percent to 7 percent or more in early 2009.

The relentless job-cutting in the US - the report for September registered the ninth straight month of payroll declines - is indicative of a systemic crisis of the capitalist system that erupted first in the United States but is increasingly reverberating around the world. The Eurozone countries are now in recession and layoffs are mounting in most of the major industrialized countries, particularly in the financial sector and the auto industry.

This week alone, the Swiss banking giant UBS announced it would cut 2,000 more jobs - a further 10 percent of its investment banking work force. The bank, which has written off $43 billion in bad loans over the past year, earlier announced 4,000 job cuts at its investment bank.

Lehman Brothers' European fixed-income division announced it would wind down its operations, laying off 750 employees.

Recent surveys have shown that manufacturers across the world's advanced economies, including the US, Europe and Japan, are slashing output. The slump has hit particularly hard in the auto sector.

This week, Volvo Trucks announced it was cutting more than 20 percent of its European blue-collar staff - some 1,400 employees at its three plants in Belgium and Sweden. Volvo cars, owned by Ford, last month accelerated plans to cut 2,000 jobs and said it would need to cut an additional 900 next year. Auto components plants that supply Volvo said they were cutting jobs.

Ford and Volkswagen have both cut jobs at their car plants in Belgium.

In the US, General Motors announced Friday it would close its sports utility vehicle plant in Moraine, Ohio by the end of this year, laying off 1,200 employees, most of them hourly workers.

The slump in auto sales over the summer has been accelerated by the freezing up of credit markets, making it more difficult for consumers to obtain loans to purchase new cars. Auto sales in September plummeted in both the US and Europe. They declined 32 percent in Spain, 6 percent in Italy and 2 percent in Germany.

Auto companies in Britain are cutting output, introducing three- and four-day work weeks in some plants. Ford is scaling back production across Europe.

In the US, the sales figures for September were even worse than in Europe, hitting Japanese as well as American auto makers. Overall sales of cars and light trucks fell 27 percent last month, compared to a year earlier.

The biggest drop among the US Big Three companies came at Ford, which reported a 34 percent decline. Chrysler sales fell 33 percent and GM reported a 16 percent drop.

Among Japanese producers, Toyota sales in the US were down 32 percent, Nissan Motors saw a 37 percent decline, and Honda sales were down 24 percent.

Major US dealerships are starting to go out of business, and analysts expect that trend to accelerate.

The US Labor Department jobless report registered the biggest monthly drop in payrolls in more than five years. It brought the net job loss so far this year to 760,000. The shrinkage in payrolls was spread throughout most of the economy.

Manufacturing lost 51,000 jobs. Construction fell by 35,000 jobs. Retailers shed 40,000 workers. Leisure and hospitality industries cut 17,000 jobs. Professional and business services reduced their payrolls by 27,000.

Service sector employment, which until recently had seen smaller declines than in goods-producing industries, fell 82,000 in September, the biggest drop in more than five years.

Employment in manufacturing in the US is now down by 442,000 from its year-ago level. Of this, the auto sector has lost 140,000 jobs.

The official unemployment rate remained at 6.1 percent, but this measure vastly underestimates the real level of joblessness, because it does not count laid off workers who have stopped looking for a job or those working part-time because they cannot get full-time employment.

The number of people working part-time because they couldn't find a full-time job or because their hours had been cut back due to slack business conditions jumped by 337,000 to 6.1 million.

A more accurate gauge of unemployment included in the Labor Department report, the so-called under-employment rate, rose to 11 percent from 10.7 percent, the highest rate for that measure since April 1994.

Another measure of the slumping jobs market and growing economic distress, the average hourly work week, slipped by 0.1 hours to 33.6. A mere 3-cent gain in average hourly salary, combined with the shorter work week, means that the average weekly paycheck fell by 81 cents to $610.

Unemployment for men rose by 0.5 percent to 6.1 percent. The jobless rate for black men jumped 1.6 percent to 11.9 percent, the highest since February of 1994. Unemployment among workers with high school degrees only stood at 9.6 percent.

"The US economy is shrinking, and there will be many more awful reports like this," said Ian Shepherdson, chief US economist at High Frequency Economics.

Other economic data released this week confirm this prognosis. The Commerce Department reported that US factory orders fell by 4.0 percent in August, far more than the consensus forecast of economists, who predicted a 2.5 percent decline.

The Institute for Supply Management said its survey of US manufacturers indicated output falling at its fastest rate since October 2001.

The number of US workers filing new claims for unemployment benefits neared the half-million mark last week, hitting a fresh seven-year high.

Earlier this month, the job placement consultancy firm Challenger, Gray & Christmas reported that job cuts announced by US employers in August jumped 12 percent over a year ago to cap the biggest summer of downsizing in six years.

Employers announced plans to reduce their work forces by 88,700 jobs in August. For the summer period of May through August, job cuts totaled 377,000, up from 249,000 in the summer of 2007. That lifted the total of announced cuts in 2008 to 668,000, up 29 percent from 516,000 in the first eight months of 2007.

The vicious cycle of contracting credit, resulting from the implosion of the housing and credit bubbles, mounting layoffs, slumping consumer spending and a worsening of the financial crisis continues to deepen. There are many signs that the credit crunch will continue to undermine major companies.

A growing list of hedge funds, hit by their exposure to Lehman Brothers and other failed firms, are facing rising withdrawal requests and are telling their customers they cannot have their money back.

Billions of dollars in contracts on now-defaulted credit default swaps on Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Lehman Brothers and Washington Mutual are due to be settled this month, with the likely result of billions in additional losses for major financial firms.

The collapse of confidence in the credit-worthiness of major banks has led to a virtual freeze in the market for commercial paper, short-term debt issued by a wide range of companies to finance their day-to-day operations. The market for commercial paper in the US has fallen from $2.2 trillion last summer to $1.6 trillion today.

The drying up of credit is throwing small and large companies, state and local governments, colleges and other institutions into a sudden crisis, where they lack the cash needed to meet payrolls, pay bills and buy essential items. One corporate giant whose viability is now suspect is General Electric, which this week announced an emergency plan to raise capital by selling $12 billion in common stock. In a sign of the times, billionaire investor Warren Buffet agreed to inject $3 billion of capital into GE, through the purchase of preferred stock (on highly favorable terms), in a bid to restore market confidence and stem a sharp decline in GE stock.

As the Wall Street Journal wrote: "Indeed, this week, General Electric Co., long hailed as one of the steadiest companies in America, was forced to raise billions of dollars of capital on onerous terms partly because investors in GE's short-term corporate debt fretted about its rising borrowing costs. On Wednesday, a money fund catering to educational institutions froze withdrawals - sending more than 1,000 colleges and schools scrambling to ensure they have cash to pay teachers and cover expenses."

On Thursday, California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger sent a letter to Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson warning that the largest state in the US might be forced to ask for a $7 billion emergency loan from the federal government.

There is little belief in financial markets that the $700 billion-plus US government handout to Wall Street, approved by Congress and signed into law by President Bush on Friday, will resolve the financial crisis or avert a long and protracted recession. The Dow Jones Industrial Average was actually up more than 200 points before the House of Representatives voted to approve the bailout, but it fell steadily thereafter, closing with a loss of 157 points.

Germany Moves to Shore Up Confidence in EconomyFinally, here is a very interesting speech on the House floor by Rep. Brad Sherman about how the US administration threatened martial law if the bailout plan wasn't passed. A peek behind the curtains:

Carter Dougherty

NY Times

October 6, 2008

FRANKFURT - The German government said on Sunday that it would guarantee all private savings accounts in the country in an effort to reinforce increasingly shaky confidence in the financial system. The announcement came as the leaders of largest European economies met over the weekend searching for a systemwide answer to a credit crisis that has required them to rescue several banks in just the past week.

Germany's guarantee of its private savings - worth about 500 billion euros, or more than $700 billion - followed the news that a group of banks had pulled out of a deal to provide 35 billion euros, or $48.2 billion, to rescue the large German mortgage lender, Hypo Real Estate.

Later in the day, the Belgian government announced that the French bank BNP Paribas would take a 75 percent stake in the remaining operations of troubled bank Fortis NV, The Associated Press reported. The Netherlands had effectively nationalized the Dutch operations of the bank on Friday after a joint rescue deal with Belgium and Luxembourg broke down.

Belgian Prime Minister Yves Leterme said the deal gives the Paris-based Paribas control of the Fortis Belgian and Luxembourg operations, including the bank's insurance and investment arms. The Belgium and Luxembourg governments also will receive a blocking minority share in BNP Paribas.

"No client or depositor will end up in problems due to the financial crisis," Leterme told reporters late Sunday after two days of closed-door talks between BNP Paribas and government officials.

In Iceland, where the government seized control of a bank last week, officials were considering more sweeping measures to stabilize finances there as well. And the board of UniCredit, which is based in Milan and also operates in Germany and much of Eastern Europe, met to consider a capital increase after being buffeted by a week of speculation about its solvency.

And however dramatic, the German move to guarantee private savings stops short of what Ireland did with its banks last week. The Irish government backstopped savings accounts as well as other liabilities of six domestic banks, a step that effectively lent a sovereign guarantee to creditors of the banks, and ensured their solvency.

In meetings in Paris over the weekend, the Europeans did not agree on a broad bailout along the lines of the $700 billion package that President Bush signed into law Friday. Instead, the leaders of France, Germany, Britain and Italy pledged on Saturday to prevent a bankruptcy on this side of the Atlantic like the one that brought down Lehman Brothers, the American investment bank.

The credit crisis has become the biggest financial challenge for European policy makers in a decade. European countries lack a common budget and uniform regulations for cross-border banks and brokerages, hampering their ability to enact a large bailout program like the one passed in Washington.

European leaders said they would try to rewrite European accounting rules by the end of the month to limit the losses banks have to write off, an effort to match changes in "mark-to-market" accounting rules in the United States while keeping the European financial sector competitive. They stopped short of calling for an overarching banking regulator for Europe but proposed creating a panel of European regulators to jointly oversee large financial institutions with operations in different countries.

In Germany over the past week, media reports about the banking crisis had created "great uncertainty" among ordinary citizens, thus prompting the guarantee of private savings, said a spokesman for the finance ministry, Stefan Olbermann.

Worried that the continued turmoil at Hypo Real Estate would trigger a retail panic at other German banks, Chancellor Angela Merkel and her finance minister, Peer Steinbruck, made a rare Sunday appearance before television cameras on the steps of the Berlin chancellery to assure a jittery public about the safety of their savings.

"This is an important signal so that it comes to some calming down, not to reactions that would be out of proportion and would make our crisis management and crisis prevention that much more difficult," Mr. Steinbruck said. Mindful of the rising public anger at the use of public money to buttress the business of high-earning bankers, Ms. Merkel promised a day of reckoning for them as well.

"We are also saying that those who engaged in irresponsible behavior will be held responsible," Ms. Merkel said. "The government will ensure that. We owe it to taxpayers."

German deposits are already guaranteed through a mixture of deposit insurance plans, with the first line of defense being a state fund. A second are the programs to which Germany's different public, private and community banks contribute. The Finance Ministry said the new blanket guarantee was effective immediately, although it was unclear if new legislation would be needed. "We think this will create the confidence we need," Mr. Olbermann said. "That means the cost could be nothing."

Senior German officials huddling in the chancellor's office on Sunday morning were joined by Josef Ackermann, chief executive of Deutsche Bank, and Klaus-Peter Muller, chairman of both the Association of German banks and Commerzbank, a large retail and corporate bank.

The rescue of Hypo Real Estate announced last Monday quickly fell apart over the company's liabilities, which are linked to the American municipal bond market, according to a person briefed on the talks, who requested anonymity because the outcome was still unclear.

Depfa, a Dublin-based lender that Hypo acquired last year, is at the center of its problems. Depfa underwrote a package of municipal bonds which were subsequently downgraded by ratings agencies. That step obliged Depfa to buy the bonds back, a contractual requirement that would create almost immediate liquidity problems at Hypo itself, given the difficulty of getting short-term funding in today's drumtight credit markets. Banks from outside Hypo uncovered the problem after the bailout was cemented last week, and soon realized that the 35 billion euros that were supposed to sustain the bank through the end of 2009 was inadequate. Instead, it would need 50 billion euros by the end of this year, and another 10 billion in 2009. After the magnitude of the problem became clear, the banks - which were not publicly identified - revoked their participation in the plan, which had been a joint public-private deal.

As I selected a clip (the quote from "badtux) from last week's commentary, shared it with my 3rd congressional-district congressman (I included the link to the entire piece) and even urged him to debate those contents (regarding Ben Bernanke's lifelong financial knowledge/experience)

I did receive a response via email. Yet, unfortunately notwithstanding, Rep Udall's steadfastness in opposing such endeavours to Reward all these Wealthy Parasites...

I'll simply quote the reply in his own words:

October 7, 2008 2/seed (Kan)

Mr. Richard S. King

328 Grand Avenue, Apartment 2

Las Vegas, New Mexico 87701

Dear Mr. King:

Thank you for contacting me regarding America's economy and efforts to bail out Wall Street. I appreciate your interest in this important issue. Last Friday, for the second time, I voted against a deeply flawed plan to bail out Wall Street with $700 billion of taxpayer money. That legislation had changed little from the bill I voted against four days earlier. While I believe Congress should act to help middle class families-and I have fought for economic stimulus legislation that will help produce jobs for American workers-we should not do the wrong thing just to say we did something. With a proposal as large as the one proposed last Friday, we have to get it right. That bill fell short. However, despite my opposition, the bill passed by a vote of 263 - 171. Below is my statement from last Friday's Congressional Record.