Large swaths of the region are on track to experience their wettest winter on record, with many areas having already surpassed their average precipitation for an entire year.

And all that water is putting new strains on the network of dams, rivers, levees and other waterways that are essential to preventing massive flooding during wet years like this one.

The biggest danger zone lies in the Central Valley at the base of the Sierra Nevada, whose tall peaks can wring the skies of huge amounts of rain and snow. The area is essentially one giant floodplain that would be easily transformed into an inland sea without man-made flood control. At 400 miles long and 40 miles wide, it has only a tiny bottleneck from which to drain — a one-mile opening at the Carquinez Strait at San Pablo Bay — before water heads into the San Francisco Bay.

"You got this big bathtub — water doesn't flow out of it very quickly," said Jeffrey Mount, senior fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California and former director of the UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences.

As the site of the nation's tallest dam and the main storage for the State Water Project that sends water to the Southland, Lake Oroville has commanded national attention as the crippled spillways forced the evacuations of more than 100,000 downstream. But smaller water systems are also under intense pressure.

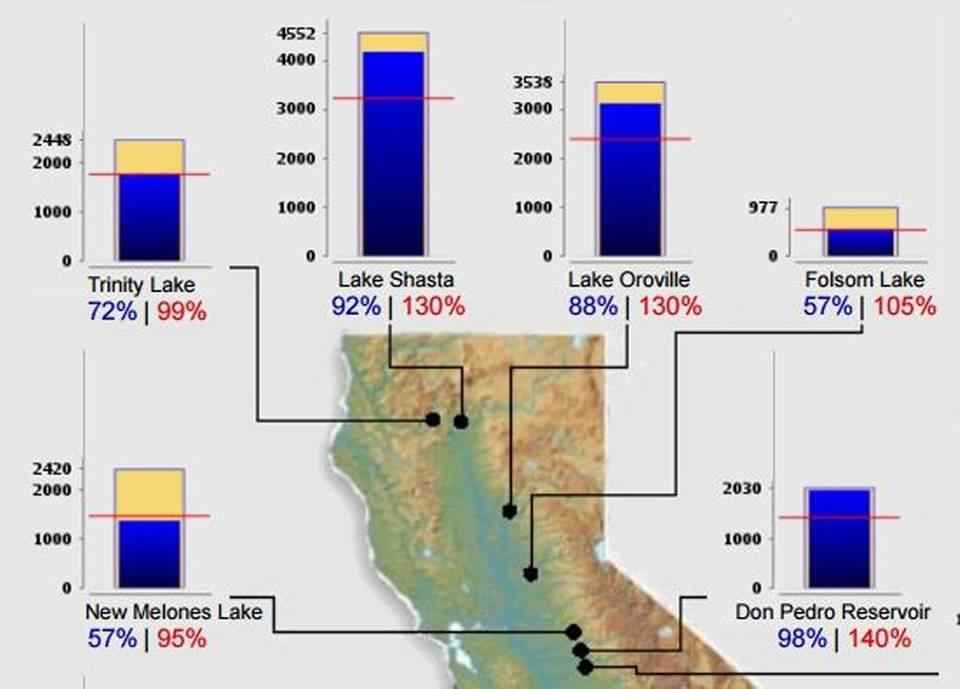

Sixteen reservoirs, ranging from small to the biggest in the state, were above 90% full as of Wednesday morning.

Among them is the Don Pedro Reservoir, the sixth-largest in California and located near Yosemite National Park. As of Wednesday afternoon, it stood at an elevation of 827.4 feet, just shy of its 830-foot capacity, the Turlock Irrigation District said in a statement. The district continued to make releases to the Tuolumne River, which flows through Stanislaus County and into urban centers such as Modesto.

Forecasters predict about 4.7 inches of precipitation could fall in the watershed over the next six days. Although the irrigation district said it does not anticipate an overflow, it advised residents of Stanislaus and Merced counties to register for emergency notifications.

In the Sacramento Valley, Shasta Dam, the spigot for California's largest water storage lake, and Keswick Dam both released large volumes of water for multiple days into the Sacramento River.

The National Weather Service's California Nevada River Forecast Center warns that the San Joaquin River at Vernalis in San Joaquin County will surge into the "danger stage" this weekend, the first time this winter that the center has made such a warning. That could put the town of Lathrop, south of Stockton, at risk.

Earlier this week, evacuation orders were issued for Tyler Island, a small farming tract in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, after a compromised levee posed a risk of flooding.

To water experts, it's a pattern that plays out in years of heavy rains. Lakes pushed to capacity have placed tremendous strain on levees, some of which were built long ago and were weakly constructed. Perceived as fail-safes, experts say levees were meant to reduce the frequency of floods, not stop them altogether.

"They're really the No. 1 defense against floods, and they're not very good at it," Mount said. "Levees are kind of unreliable partners in flood management."

Hoping to avoid the situation faced by Lake Oroville, officials are planning large releases of water from reservoirs. But that could further strain the hundreds of miles of levees that line the Central Valley's vast river networks, built to protect homes, businesses and farms from floods. The series of storms that slammed the area in December 1996 and lasted for a week caused numerous levees to collapse. Widespread flooding that inundated 300 square miles led to extensive damage and evacuations of 120,000 people, as well as nine deaths.

While the state's reservoirs are built to release water slowly, officials are forced to quicken the pace of releases when they are at capacity. Water from brimming reservoirs is guided into nearby rivers. If those rivers are full, water can seep over and under levees, or through hidden cracks, leading to erosion.

More expected storms this season and a massive snowpack likely to run off into the summer has officials grappling with their options.

"After several years of drought, now we've got too much all at once," said Jeremy Hill, a civil engineer who is part of the Department of Water Resources flood operations team.

Hill said the threat of floods would be a lasting concern until the end of spring.

Levees were not designed to be stressed for extended periods of time and they require constant supervision, said Joseph Countryman, a member of the Central Valley Flood Protection Board and former head of reservoir operations for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for Northern California, Nevada, Utah and Colorado. Even without major rainstorms, the magnitude of the volume of water flowing through the system will still create "tremendous seepage" in the levees, potentially weakening them. And significant flows are to be expected through June, he said.

"The longer the water is on levees, the more potential they have to become saturated and develop problems they have never before exhibited," he said.

State water officials said despite the record rainfall, they remain confident the flood control systems will hold up.

"There's a lot of water moving around and everything's full and everybody's going to have plenty of water," said Bill Croyle, the acting director of the Department of Water Resources who was at incident command headquarters for the Oroville Dam. "I don't think it's testing the system."

Even as rain began to fall Wednesday, Croyle said the storms forecast over the next few days will not be enough to test the integrity of the Oroville Dam or its two damaged spillways. He said the public "won't see a blip in the reservoir" levels, now dropping about 8 inches an hour.

Officials at the dam said their biggest worry wasn't the weather but the damage done to the dam's already compromised main spillway during days of sustained pounding from heavy releases of water. When the emergency spillway began to fail Sunday, officials sent massive amounts of water down the main spillway — despite the damage — in a desperate effort to reduce the water level in the reservoir.

"It's holding up really well," Croyle said of the main spillway. But he added continued mass water releases could be causing hidden damage to the rocky subsurface adjacent to the concrete chute.

Reader Comments