It's like nothing scientists have witnessed in West Antarctica before, and it doesn't bode well for the ice sheet's future.

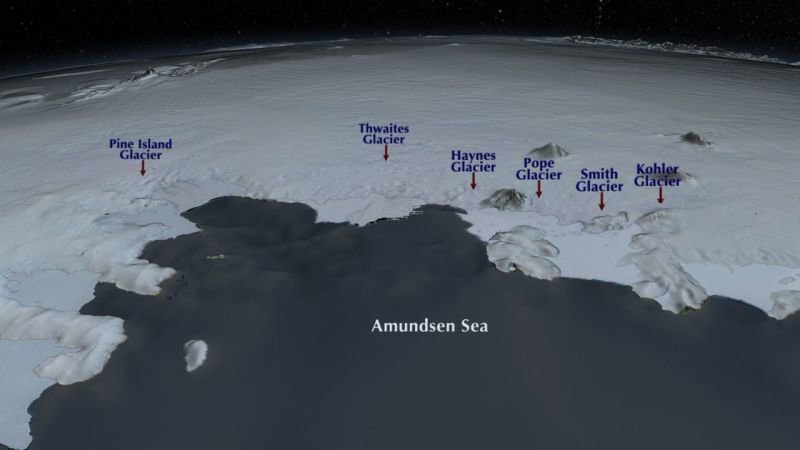

A frozen fortress containing enough water to raise global sea levels many feet should it melt, the West Antarctic ice sheet is separated from the ocean by a series of large glaciers. For now, these glaciers act like corks in wine bottles to hold the ice at bay, but that may not be the case for much longer. Recent research has shown that Pine Island, Thwaites, and other glaciers along the Amundsen sea are retreating rapidly, as warm ocean waters lap against their margins. At this point, NASA says, collapse of the entire Amundsen sea sector appears to be "unstoppable."

The biggest question on everyone's mind is how quickly all of that ice will go, and to find out, we need to pinpoint the mechanisms responsible for ice sheet collapse. To that end, a study published today in Geophysical Research Letters takes a deep dive into an iceberg calving event in the summer of 2015. It arrives at a startling conclusion.

"The calving event itself wasn't a big deal," lead study author Ian Howat of Ohio State University told Gizmodo, noting that iceberg break-offs of this size happen about every 5 to 6 years at Pine Island. "What made this one different is how it got started."

Not so with last year's Pine Island calving event. Analyzing several years of images taken by the Sentinel-1A satellite, Howat and his colleagues traced the break-off to a rift that formed at the base of the ice shelf nearly 20 miles inland, in 2013. Over the course of two years, the rift propagated all the way from bottom to top, until finally, it spat out an iceberg ten times the size of Manhattan.

What could have caused so much ice to break away in this unusual manner? In all likelihood, melting that started at the contact point between ice and bedrock is to blame. This would explain why the rift overlapped with a topographic valley—a place where the ice appeared to have thinned—in satellite images taken before the calving.

"I think what we're seeing is the surface expression of a much bigger valley at the base of the ice shelf," Howat said. "This tells us the ice shelf has weaknesses that are being exploited by increased ocean temperatures."

Troublingly, as waters around West Antarctica heat up, those weaknesses could be exploited more and more often. "If the ice sheet was going to retreat very slowly on long timescales, we'd just expect to see the usual calving," Howat said. "This event gives us a new mechanism for ice sheets falling apart quickly. It fits into that picture of a rapid retreat."

Howat noted that a second interior ice shelf rift (pictured above) was spotted during a NASA Operation Ice Bridge survey earlier this month. And there are many other topographic valleys—possible sites of future calving events—further up-glacier, but our ability to study them is hampered by a lack of good data.

One can't help but note that NASA's Earth science program, which makes such data available to scientists and the public, faces the possibility of major cuts under a Trump administration. These cuts would come at the precise moment when our planet is changing in rapid and hard-to-predict ways, which is when Earth science research is needed the most. Like cracks in an ice sheet, the irony runs deep.

Comment: While the breaking up of the West Antarctic ice sheet is concerning, keep in mind that glacial rebound can occur suddenly, especially when paired with global warming, and that glacial retreat can occur directly before glacial rebound. Ice Ages occur much, much faster than thought: