© Daniel Heuclin/naturepl.comA timber rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus)

In 2006 biologists studying the only

timber rattlesnakes in the state of New Hampshire recorded something alarming:

a population crash.

The already rare animals - numbering about 40 in total - began dying in unusually large numbers. No more than 20 rattlesnakes survived, and the population remained at that new super-low level five years later.Many of the snakes showed signs of a severe skin infection on their heads and bodies just before they died.

It was an early sign of a deadly fungal disease that is now sweeping through the snakes of eastern North America.Today at least 30 species are affected. "Snake fungal disease" has been documented in

more than 16 US states and in

parts of Canada. How worried should we be?

Snake fungal disease generally begins with a relatively mild skin infection, often - but not always - where a snake's skin has been physically damaged.

The snake's immune system kicks into action, but within a few days the skin at the infection site has begun to thicken and die, creating a yellow or brown crust. In some cases this crust breaks off, exposing raw flesh and allowing the fungus to spread.

If the infection reaches the head it can interfere with the snake's eyes or sense of smell, leaving the animal unable to hunt and prone to death by starvation.

Even if the infection remains confined to the body, it can interfere with the snake's behaviour in a way that raises the risk of death. For instance, some infected snakes bask out in the open air at times of the year when they should be hibernating. Doing so raises their body temperature and helps their immune system fight the disease, but it can leave the snake vulnerable to death if ambient temperatures drop suddenly.

This sort of detailed information might give the impression that snake fungal disease is relatively well understood by biologists. That could hardly be further from the truth.

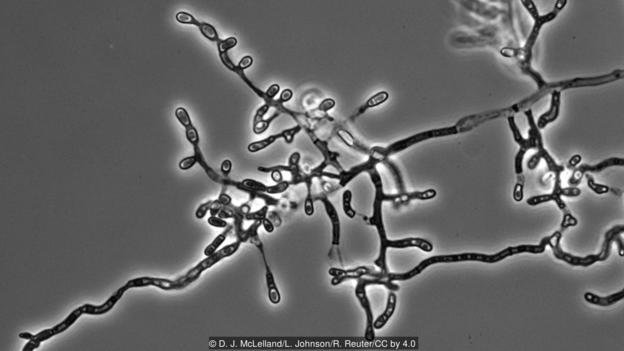

© D. J. McLelland/L. JohnsonOphidiomyces ophiodiicola

In fact, until 2015 it was not even clear which fungus triggers the disease.

Two studies, published a month apart, formally identified the culprit. Both found that healthy snakes developed the disease if they were infected with a soil fungus called

Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola.The curious thing is that

O. ophiodiicola appears to have been present in North America long before snake fungal disease flared up.

"It's in so many different habitats," says

Matt Allender at the University of Illinois in Urbana, who co-authored one of the two studies. "I think it was widespread across all landscapes, and certain factors have caused it to emerge as a pathogen-causing disease."

Exactly when the fungus turned into a snake killer is also unclear.

© Lynn M. Stone/naturepl.comEastern massasauga (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus)

at the US Geological Survey - National Wildlife Health Centre in Madison, Wisconsin was a co-author on the second

O. ophiodiicola study. He points out that there are sporadic reports of snakes with skin lesions going back decades. "[But] we have not yet been able to definitively prove that these older cases were caused by

Ophidiomyces," he says.

Research by Allender and his colleagues suggests

O. ophiodiicola might have begun attacking snakes very recently.

The scientists

trawled through museum collections across Illinois, one of the states badly affected by snake fungal disease today. "We looked at every

massasauga [a type of rattlesnake] specimen that came in since 1880, and re-evaluated and re-examined any animal with any evidence of clinical signs consistent with snake fungal disease," says Allender.

Then the team studied samples from lesions that could have been caused by the fungus and looked at their molecular makeup.

"We saw zero occurrence of the fungus from 1880 all the way through to 1999," says Allender. "The year 2000 is when we start to see its emergence in the area."

This suggests that an event at the turn of the millennium led a relatively benign fungus to become a potent snake killer.

© Daniel Heuclin/naturepl.comBanded water snake (Nerodia fasciata)

However, nobody knows what that trigger was. "It is unclear why the disease seems to be becoming more problematic," says Lorch.

It might be significant that environmental conditions in eastern North America were unusually wet in 2006, the year snake fungal disease was first documented. Cool and damp conditions certainly favour fungal activity, as Lorch and his colleagues pointed out in a

paper published in October 2016.But, paradoxically, they also say that unusually hot and dry weather could have been a triggering factor. Such conditions might have encouraged snakes to spend more time underground to escape the heat. That could have put them into prolonged contact with the soil-dwelling fungus, giving it more opportunity to attack.

It might be significant that

O. ophiodiicola seems to have a greater chance of infecting snakes hibernating in warmer soil, as Allender and his colleagues reported in 2015.

Another of their studies, published in July 2016, suggests a human factor in the rise of snake fungal disease.

They explored which disinfectants are most effective against Ophidiomyces."We found several things would kill the fungus: bleach, alcohol and over-the-counter cleaners," says Allender. "But what didn't kill it was an agricultural fungicide. It's concerning. Is the emergence of widespread fungicide use linked to emergence of some of these fungal diseases?"

Working out why

O. ophiodiicola became so deadly is clearly important. But arguably there is an even more urgent question to answer: exactly how deadly is the fungus?

© Daniel Heuclin/naturepl.comMassasaugas (Sistrurus catenatus) are affected

Some affected snakes seem to fare better than others.

In a few species snake fungal disease is having a truly devastating impact. "The main species I look at is a rattlesnake called the eastern massasauga," says Allender. "They have a 92.5% mortality rate from the disease.""In many areas, snake populations are highly fragmented and already in trouble from other threats," says Lorch. "It is these cases where we worry about snake fungal disease contributing to [local or regional] extinction."

Even a reduction in snake numbers - falling short of outright extinction - could be bad news.

Snakes are an important part of the ecosystem, because they hunt rodents and other animals that can carry diseases. If snakes begin to disappear from the landscape, these dangerous diseases could become more commonplace. That could pose a threat to human health.

Unfortunately, what little evidence there is suggests snakes are on the decline across the world.

© MYN/Paul Marcellini/naturepl.comMud snakes (Farancia abacura) )

In 2010,

Chris Reading at the Centre for Ecology & Hydrology in Wallingford, UK, and his colleagues reported evidence of

sharp snake population drops in the UK, France, Italy, Nigeria and Australia."It is possible that environmental pressures on snakes, such as habitat loss or degradation, climate change and prey availability, could all potentially impact on a snake's physiology," says Reading. "[That] might therefore result in a reduced ability to resist otherwise mild infections."

So how worried should we be about snake fungal disease? It is probably too early to say for sure, but it could prove to be a big problem.

To make matters worse, snakes have a terrible public image. That means drumming up support for research into snake fungal disease is a challenge.

© Pete Oxford/naturepl.comTimber rattlesnakes (Crotalus horridus) can be black

"It's hard to get people excited about snakes. It's not a group of species that many people care much about," says Allender. "And most cases of the disease are in venomous species, which makes it even more difficult to get them excited."

North American bat researchers faced a similar public-relations battle a few years ago, when another devastating fungal infection - white-nose syndrome - began killing the flying mammals in large numbers.

Allender says the bat researchers did a "really good job" of explaining that

bats bring economic benefits: for instance, by hunting and killing insects that might otherwise eat crops.

"There's a really direct link between bats and agricultural food supplies," he says. "But with snakes we can't simplify the narrative as much."

This might be the biggest challenge the snake biologists face. Finding a way to make the public care about the plight of snakes could be a necessary first step in the fight against snake fungal disease.

That seeings how the GMO's are detrimental to humans, what do you suppose they are doing to other species.??GMO's are modifying the world as we know it.