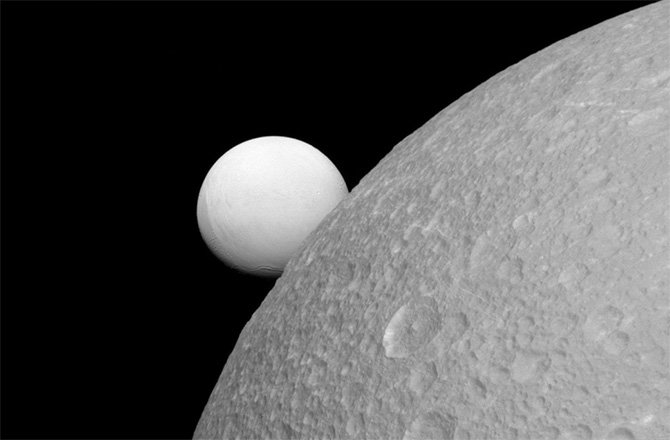

The data comes from NASA's Saturn-orbiting Cassini spacecraft, which in October made its deepest dive into plumes of vapor and ice jetting off the southern polar region of Enceladus, a 310-mile wide moon that has emerged as a top contender in the search for life beyond Earth.

"This is really is a world with a habitable environment in its interior," planetary scientist Jonathan Lunine, with Cornell University, said at the American Geophysical Union conference in San Francisco.

Early analysis of Cassini's 30-mile high pass over Enceladus on Oct. 28 indicates that the moon's subsurface ocean, which is believed to be the source of the plumes, has telltale chemical fingerprints of water that has interacted with rock.

"This is remarkably high pH solution," said geochemist Christopher Glein with the University of Toronto and the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado.

"How did it get that way? We think that what happened on Enceladus, and which could still be happening today, is that there were geochemical reactions between magnesium and iron-rich rocks in Enceladus' core reacting with ocean water. Those reactions led to the high pH," Glein said.

The process, known as serpentinization, has been found on Earth, such as in Lost City, a field of alkaline hydrothermal vents in the mid-Atlantic ocean.

Another geochemical consequence of serpentinization is the mass production of hydrogen gas.

So far, attempts to tease out signs of hydrogen in Enceladus' plumes has had mixed results.

But if confirmed, the presence of hydrogen could have significant implications for the prospect of life, Glein said.

"Hydrogen ... has the potential to drive the synthesis of organic molecules -- and much more," Glein said.

In addition, if life ever arose on Enceladus, it could use hydrogen.

"Microbes love the stuff, they love to burn hydrogen because it releases a lot of energy when they react it carbon dioxide," Glein said

Cassini, which has been orbiting Saturn for more than 11 years, is due to make its final flyby of Enceladus on Saturday.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter