Jon Stewart is right: the U.S. most definitely is NOT a post-racial society. But before we, as Dutch citizens, start lecturing Americans about the state of their nation, we ought to come clean about our own racist proclivities. Every year on December 5th Dutch children celebrate a kind of mini pre-Santa day of gift-giving (well, gift-receiving in the kids' case, but the adult population joins in the fun too). The centerpiece of Sint-Nicolaas Day are parades in every town and city up and down the country, in which the guest of honor is a very Father Christmas-like figure who gives kids candy... with the assistance of 'Black Pete', his negro servant sidekick.

To understand this toxic Dutch 'tradition', you have to understand some of its past. But first, here's the story of "Sint-Nicolaas and Black Pete" as it is presented today.

Sint Nicolaas and his Servants

Saint Nicholas' Day, usually December 6th, is the feast day of Saint Nicholas in many Western countries. In most of those countries, it's no longer a big deal because gift-giving celebrations around the Winter Solstice take precedence. In the Netherlands (and Belgium), however, 'Saint Nicholas eve' (December 5th) is nearly as big a deal as 'Christmas proper'.

The Dutch December 5th/6th 'Sint Nicolaas' is based on the same basic Saint Nicholas myth, celebrated annually with the giving of gifts on the eve of Saint Nicholas' Day (December 5th). Sint Nicolaas is portrayed as an elderly man with a flowing white beard, much as 'Father Christmas' is. But instead of flying reindeer and elvish toy-makers, Sint Nicolaas has servants called 'Black Petes' who act goofy and funny while handing out candy to children. Sint Nicolaas and entourage arrive on a steamboat from Spain, then the old man rides a white horse through town (don't ask, no one knows why). Where once there was one Zwarte Piet, now many 'Black Pete' assistants throw candy and cookies into the cheering crowd. Harmless fun, right?

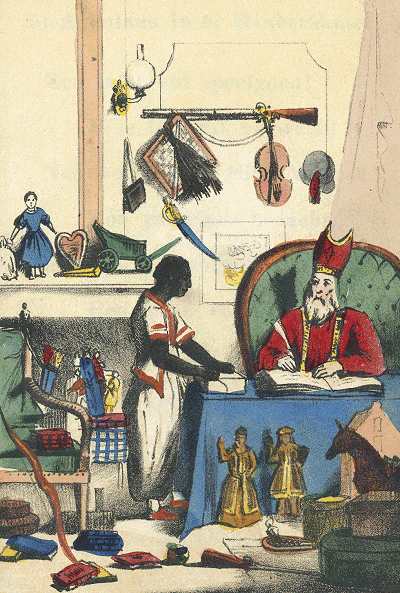

The Dutch to this day believe 'Black Pete' to be based on historical events, or a relatively unbroken tradition going back centuries. However, this particular part of their 'Christmas Tale' arose in the 19th century. Sint Nicolaas had no servants or companions between the 16th and 19th century1. In 1850 a school-teacher named Jan Schenkman published an illustrated book called Saint Nicholas and his Servant, in which the servant is depicted as a young, black male wearing traditional Moorish garb.

Between then and now, Black Pete's costume went from Moorish attire to an exaggerated 16th century Renaissance era wardrobe (again, don't ask why, although it may have something to do with the 16th century being the golden era of Dutch imperialism and slave trade). The distilled result we have today is white people dressed to look like black people in clown-like outfits as the Dutch Saint Nick's 'little helpers'.

Like much else when it comes to 'historical traditions', the individual parts make no sense and yet somehow they have come together to form part of the Dutch collective identity. Think of giant bunny rabbits leaving chocolate eggs in commemoration of the death and resurrection of a crucified mythological figure. The problem with this Dutch tradition is that - unlike elves, giant bunny rabbits, flying reindeer, and reanimated dead people - black people are very much real. Not only are they real, they have historically been, and to a large extent continue to be, treated abominably.

Lack of Moral Criticism in Dutch Society

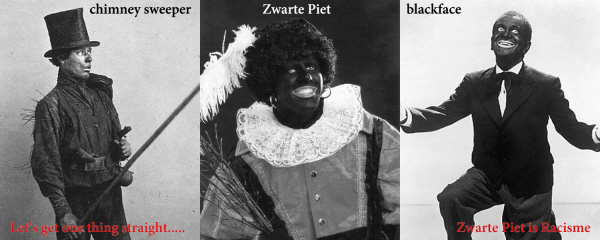

Now, if you ask Dutch people why their Saint Nick's servants/helpers are black, most will tell you their faces are blackened with soot as a result of climbing down chimneys to deliver the boss's gifts. This can be quite confusing, and make no sense to people outside of the Netherlands. Does everyone who climbs down a chimney end up with an afro, big earrings, and bright red lips? Side-effects of falling down the chimney head-first, perhaps? Hardly.

Given the historical context (the Netherlands was the last European country to abolish the slave trade - more on that below), the Schenkman formulation of Sint Nicolaas' helper being a Moor from Spain, and the black-face worn by people re-enacting the ritual today, it's very clear that Black Pete was not a 'soot-covered ethnic Dutch boy', but a black boy. A picture posted by the No Black Pete organization on their blog site illustrates this point further.

To see how non-Dutch people react upon learning about 'Black Pete', watch the recently-released documentary, 'Zwart als Roet' (Black as Soot), by Dutch filmmaker and journalist Sunny Bergman. In this documentary exploring racism in the Netherlands, Bergman conveys how deeply biased Dutch society is, and what kind of impact the Black Pete tradition has had, and is having, on people of all color. While two 'Black Petes' and a Sint Nicolaas walked around a park in London asking people for their opinions, English actor and activist Russell Brand made an appearance and said the following:

"What this tradition does, is that it dehumanises people that are of a different ethnicity and it reduces them to a lower status of either toys or a degenerative role as servants."In a survey of 1,700 Dutch citizens conducted in 2013 by Peil.nl, 92% didn't consider the depiction of 'Black Pete' to be racist, nor did they associate him with slavery. In addition, 91% didn't want the character's appearance to be changed. Another survey of 1,383 people conducted in Amsterdam, suggested that nearly three quarters of the capital's residents with a Dutch colonial (Surinamese, Antillean, or Ghanaian) background perceived Black Pete to be racist. According to new research by EenVandaag, the number of Dutch citizens wishing to see 'Black Pete' de-racialized has almost tripled, from 5% last year to 13% this year, amounting to over 1.5 million Dutch citizens who are against the current depiction of Black Pete.

"In this country we think of Holland as a very advanced nation with advanced social principles, so it's very surprising to see this kind of tradition".

Discussion about this is getting more attention, and more people seem to see the other side of the 'story'. The question remains, however; why a majority of Dutch citizens accept something that might have been acceptable in colonial times, but which has no place in a country that houses the International Court of (supposed) Justice? In 2011 in Canada, Dutch-Canadian organizers of New Westminster's 'Sinterklaas' celebrations decided to discard 'Black Pete' altogether, the first time since 1985 that Black Pete didn't appear with Sint Nicolaas during celebrations in western Canada. The Canadians did it, so what's stopping the Dutch?

A majority of Dutch citizens either simply don't care or seem to feel bound to a tradition they identify with as part of Dutch culture. They view it as innocent and fun, not only for children, but for everyone. Lacking the ability to view the matter from a different, more objective, perspective, could it be that the Dutch are not yet feeling pressure from the downward spiral their homeland finds itself in? Most of the Dutch population appears oblivious to wrongdoings in general, kept busy and content with dissociating activities, such as watching and discussing soccer, the latest fashion trends, TV shows, and participating in annual racist 'festivities'. Far from being harmless 'fun', the 'Black Pete' tradition reinforces racial division within Dutch society. And these days, with extreme right-wingers like Geert Wilders given a platform in Dutch media, racial division is STRONG. That 'Black Pete, a product of the psychopathically cynical 'white man's burden, is inherently racist and understood perfectly well as such by white schoolchildren when they bully children descended from immigrants with taunts of 'Look, there goes Black Pete!'

The following excerpt from the book Political Ponerology by Polish psychiatrist Andrzej Łobaczewski touches on this:

During good times, people progressively lose sight of the need for profound reflection, introspection , knowledge of others, and an understanding of life's complicated laws. Is it worth pondering the properties of human nature and man's flawed personality, whether one's own or someone else's? Can we understand the creative meaning of suffering we have not undergone ourselves, instead of taking the easy way out and blaming the victim? Any excess mental effort seems like pointless labor if life's joys appear to be available for the taking. A clever, liberal, and merry individual is a good sport; a more farsighted person predicting dire results becomes a wet-blanket killjoy. [...]Considering the major budget cuts right around the corner, "bad" times are here. What can ordinary people, of all colors, do to resist or defend against 'austerity measures' implemented by the government if they are divided as a nation? If we would all use our moral compasses, leave subjective opinions behind, and look at situations from a more objective point of view, we might be able to join forces in a more productive manner when it comes to demanding real solutions to pressing issues.

When communities lose the capacity for psychological reason and moral criticism, the processes of the generation of evil are intensified at every social scale, whether individual or macrosocial, until everything reverts to "bad" times.

Our 'Colonial Hangover'

Rarely discussed is the part the Dutch played in the West's slave and opium trades, and their brutal reign in the Dutch colonies (not least Indonesia). If we do not wish to explore our past and admit that we were on the wrong side of history, how then can we look at Black Pete in an objective manner? In the words of author and Nobel Prize winner Toni Morrison, we have "violently disremembered the past".

Just a few years ago, former Prime Minister Jan Peter Balkenende called for the return of the Dutch East India Company's 'industrious' mentality, prevalent in the Netherlands for three centuries. Although most today still believe that 'trade' took place, the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC), using military might and forced labour, became exceedingly rich by stealing enormous quantities of natural resources from the East. In fact, the VOC was at one point the wealthiest corporation in the world, and still holds the record. In the words of historian Hans Derks, what the VOC REALLY stands for is 'Violent Opium Company'. Why would a modern Dutch Prime Minister want to promote the kind of extreme mind-set that normalizes pillage and plunder on an absolutely gargantuan scale?

Then there was the Dutch West India Company (WIC), which enriched itself (and its owners) through the slave trade and colonies in Suriname and the Dutch Antilles. Historians estimate that more than 500,000 people were forced to work as slaves in the colonies over the course of 200 years.

When confronted on this subject, victims of cognitive dissonance will often become abusive and angry, lashing out verbally.Just like the filmmaker Sunny Bergman, who was honest about her own hidden and unconscious racism, other Dutch people go through the painful process of admitting to themselves that they are, in fact, born and raised racist, even if they think we are not. Most of us completely disregard certain social advantages that we have over our darker-skinned fellow citizens, also called white privilege. In many cases it is easier to get a job, the police leave us alone, more often than not, and we are not treated like villains or anti-social when we walk in small groups. Because we have been brainwashed into thinking that our country is "a very advanced nation with advanced social principles," we assume that we are open-minded and accepting of other cultures.That is the narrative we as a nation have been telling ourselves.

As a number of psychologists, psychiatrists and counselors explain, these responses are a natural defense mechanism when faced with something threatening to our world view.

Recent protests

In November this year more than 60 protesters were arrested during a large demonstration against the 'Black Pete' tradition.

On this matter the country's Prime Minister Mark Rutte joined the debate, appearing to back the controversial ceremony by saying: "We should not disturb a children's party in this way." Yes it is a children's party, but his comments only inflamed the situation because they whitewashed the dark stain protesters wish to expose. Sunny Bergman, by the way, was an observing journalist at the protest and was arrested along with the protesters. According to producer Monique Busman of the VPRO broadcaster, the police singled out and isolated Bergman before arresting her and confiscating her camera.

Conclusion

Black Pete has no place in a compassionate and truly 'advanced nation'. Racism remains a deep-seated issue in The Netherlands because ordinary people aren't willing to examine their assumptions. Against the backdrop of an economy going down the drain (as with everywhere else in the Western world, more and more people are losing their jobs and find it impossible to survive on social welfare), increasing police brutality, the vicious anti-Russia propaganda, and the cover-up surrounding MH17, changing attitudes in how the Dutch celebrate winter festivities may seem like 'small potatoes'. But as a permanent affront to the country's 3.5 million non-whites, 'Black Pete' serves as a fault-line along which the Netherlands can be divided and conquered by its ruling elite because it provides fuel with which psychopaths in positions of power can aggravate inter-community tensions and deflect public anger away from where it should be directed: to those Dutch Indian Company revanchists at the top.

References

1. E. Boer-Dirks, "Nieuw licht op Zwarte Piet. Een kunsthistorisch antwoord op de vraag naar de herkomst", Volkskundig Bulletin, 19 (1993), pp. 1-35; 2-4, 10.

Very interesting to see how racism is used to manipulate ordinary people in other countries besides the US . As well to learn that 'black slavery' is historically global and not just an 'American' issue that we were taught was abolished with the so called 'Emancipation Proclamation', even though we see it alive and flourishing every day here in the 'Land of the Free' (where no one is free).

Also interesting is how the 'media' twists the racist component in issues such as this (and many others) in order to push the 'divide and conquer' paradigm. Certainly there are other issues that lay deeper, but we don't even stand a chance of becoming aware of them when we are stuck in the 'black and white' of it.