HGT, which involves acquiring genetic material from another unrelated organism instead of inheriting it from a direct ancestor, is most known today for its role in antibiotic resistance and its use in genetic modification technologies.

The team's findings appear this week in the prestigious journal Nature and show that archaea have swiped dozens, and sometimes hundreds, of bacterial genes on numerous occasions. Their research shows that these gene transfers are a far more important mechanism of microbial evolution than had been previously thought.

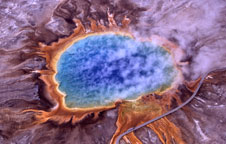

Archaea, which live in environments ranging from boiling geysers to the human navel, are single-celled microbes representing one of the three domains of life. The other two are bacteria and eukaryotes (organisms whose cells have a nucleus, such as plants and animals).

The study was led by Dr Shijulal Nelson-Sathi and Professor Bill Martin of Heinrich Heine University in Dusseldorf in collaboration with scientists from the University of Kiel, Germany and the National University of Ireland, and Otago researcher Associate Professor David Bryant.

The team used massive computer clusters to study the evolutionary history of the genes in higher archaea. They compared 267,568 protein-coding genes of 134 sequenced archaeal genomes with the equivalent genes from 1,847 bacterial genomes and established their evolutionary relationships.

The origins of 13 groups of higher archaea were unexpectedly found to correspond to 2,264 group-specific gene acquisitions from bacteria.

Many of genes taken were those involved in metabolic functions. For example, several groups of archaea whose ancestors used inorganic compounds to generate energy were now able to switch to using organic compounds and thus live in different environments.

Dr Bryant of Otago's Department of Mathematics and Statistics helped design novel statistical tests for the study.

"These results shift the balance in our ideas about microbial evolution. We had known about these gene transfers for some time. What we didn't appreciate was how they were responsible for such a huge part of microbial evolution," he says.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter