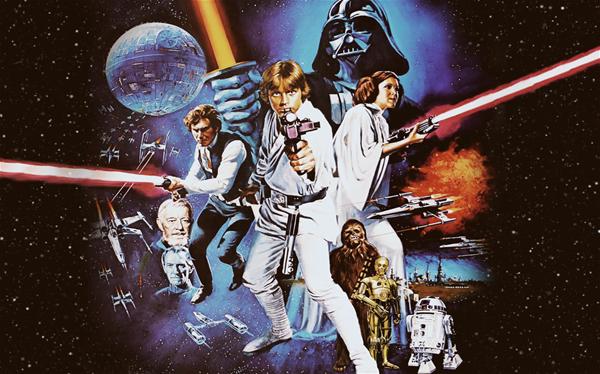

Star Wars as well as Star Trek, I'm happy to oblige.

A Long Time Ago, in a Courtroom Far, Far Away

And really, when you think about it, why shouldn't there be a look at how George Lucas's "galaxy far, far away" has subtly influenced lawyers and judges? No, I'm not talking about a clerks-like debate on the use of independent contractors in building the Death Star, the numerous OSHA violations in Jabba the Hutt's palace, or even whether a Tatooine "stand your ground" law would have gotten Han Solo off the hook for shooting Greedoin the cantina. Nor am I referring to the numerous

reported cases involving Lucas film's army of lawyers protecting the company's intellectual property rights against would-be infringers with the zeal of X-wing pilots making the Death Star trench run (and in the process, even taking exception with political groups' use of the term "Star Wars" in association with the Reagan-era Strategic Defense Initiative).1

Instead, I'm focusing on the myriad ways in which pop culture, in the form of Star Wars, has seeped into our legal culture. Do a quick Westlaw search for "Star Wars" and you'll find everything from references to strategies that the ill-fated energy giant Enron code named as "JEDI" and "Death Star"2 to a county prosecutor in Michigan named Luke Skywalker.3 The extremes of Star Wars fandom have been immortalized even in the legal literature, with litigation over marital property that included hotly disputed Star Wars action figures4 and personal injury claims encompassing a diminished ability to dress up in Star Wars-inspired costumes.5 With the plethora of exotic aliens populating the Star Wars universe, it's hardly surprising to find a few sneaking into the legal reporters.

Interestingly, there has been a number of employment discrimination, defamation, and even criminal cases in which a party took insult with a comparison to one of the creatures from George Lucas's fertile imagination. In People v. Hollis, a voluntary manslaughter case, a female friend of the defendant was compared to Chewbacca, a move that resulted in what the court called"a tragic example of what can happen when people resort to firearms as a method of conflict resolution."6 An employee of Lucas film itself even sued for alleged discrimination on the basis of gender and national origin, claiming that a supervisor had referred to her as an Ewok. The court took a dim view of her allegations, pointing out that, unlike the employee, "Ewoks are not of Arab ancestry."7 In another case (an appeal of the denial of unemployment benefits), the plaintiff, an ex-employee at a school, claimed that his female supervisor referred to him while walking the hallway as "Chewbacca."8 And in perhaps the oddest case, a solution engineer for a business software company alleged violations of the Americans with Disabilities Act over failure to make reasonable accommodations for his dwarfism and claimed that his former employer made "offensive and dismissive" references to his being "an Ewok."9 Unfortunately for the plaintiff, the judge was a fan of the truth serving as a good indication that there was no discriminating motive. Holding for the employer, the court noted that the plaintiff, a former actor, "actually was an Ewok in three Star Wars movies,"and that a website created by a friend of the plaintiff" shows a picture of plaintiff in an Ewok costume, without the Ewok head."10

In other cases, it's the settings of the Star Wars films that inspire shout-outs from the bench and bar. Trying to convey the concept of how widespread social media communications can become, and how there can be virtually no expectation of privacy in a message posted on Twitter, New York Judge (and self-confessed Star Wars fan) Matthew A. Sciarrino denied a motion to quash a subpoena for the defendant's tweets, saying, "In fact, on August 1, 2012, your tweets will be sent across the universe to a galaxy far, far away."11 Another court used the same Star Wars analogy in a commercial dispute, rejecting the plaintiff's contention that two transactions were unrelated and noting that, in fact, "the transaction was not in another galaxy far, far away."12 And in one environmental law case, the pristine Arkansas cypress swamp at the heart of the dispute was described as having been so unchanged over time that it was "like the swamp that Yoda lived in in Star Wars."13 Of course, the wild cantina at Mos Eisley - that "wretched hive of scum and villainy" with its seemingly endless variety of aliens - has also figured into a couple of judicial opinions. In a dispute over unpaid overtime and meal benefits that had beaten a complex path through the judicial system, the court observed that "similar to a Star Wars bar scene, the procedural history of this action is bizarre."14 And in the criminal case of Smith v. Scribner, the petitioner counsel's argument that the police lineup participants looked nothing like his client (or each other, for that matter) led to this amusing exchange with the trial judge:

Counsel: Other than the fact that they shared African-American descent, these people were about the same as the denizens of the Mos Isleys [sic] Space Port in Star Wars.Comparisons to particular Star Wars characters also pop up frequently in judicial opinions, which makes sense given the light vs. dark, good vs. evil dualism inherent in Lucas' sprawling space opera. The Jedi Knights, or what's left of them, are the guardians of peace and justice in the galaxy before the evil empire of Emperor Palpatine and Darth Vader casts a dark shadow. Even testimony associating the defendant with the wearing of a Darth Vader t-shirt becomes an issue on appeal in a criminal case, with the court observing that "appellant urges the court to believe that because Darth Vader is a universal archetype of evil, anyone who saw an image of Darth Vader would unfailingly recall it under any circumstances."16

Court: I am sorry. I don't go to those movies so I have no idea what you are talking about.

Counsel: All right. This is like the British judge who, when there was a reference to the Rolling Stones, said,"the Rolling What," Your Honor. All we were missing here were the Harlem Globetrotters and the Seven Dwarfs [sic].

Court: In other words, it was in the middle, not to either extreme.

Counsel: I don't think so.15

One habeas proceeding featured a forensics expert's being compared to Obi-Wan Kenobi.17 Another expert's testimony in a tortious interference and non-compete case about the "ripple effect of negativity" that contributed to the damage claims prompted a sardonic, Star Wars inspired footnote from another judge. The judge observed that it took the destruction of an entire planet (Alderaan) to cause a "great disturbance in the Force" sensed by Obi-Wan Kenobi in Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope, while the expert's conclusions were lacking in explanation.18

Perhaps the best shout-out comes from another non compete case, this time involving a dispute between rival test preparation services.19 The defendants, former employees of the plaintiff firm, Test Masters, referred to it as an "evil empire." Judge Segal, evidently a Star Wars fan, provided a helpful explanation of one defendant's promise that he would "not do anything Calrissian-esque." The court noted this "was his way of saying that he would not betray Defendant to Test Masters as the character Lando Calrissian ('the mayor of Cloud City' played by Billy D. [sic] Williams) had done in the Star Wars movie The Empire Strikes Back (Lucas film 1980)."20

Judges, of course, strive to be perceived as wise, so what better way to add a little Jedi wisdom to an opinion than by invoking Yoda, the Jedi Master himself? In a case involving the appeal of a racketeering and money laundering conviction stemming from "spas" that were allegedly fronts for prostitution, Judge Frank Easterbrook of the 7th Circuit took the prosecution to task over an inflated calculation of the illegal operation's proceeds.21 Determining that operational costs shouldn't be considered net proceeds, Judge Easterbrook channeled the tiny green Jedi in cautioning, "Size matters not, Yoda tells us."22 Justice Cunningham of the Kentucky Supreme Court took a similar side trip to Dagobah in his dissenting opinion on due process considerations and nonpayment of child support,noting: "Even Yoda, the diminutive Star Wars guru, recognized that sometimes in life we have to fish or cut bait. 'Do or not do. There is no try.' It is an admonition which fits the deadbeat parent when all of our solicitous pleadings and beseeching have led nowhere."23

Sometimes judges who channel their inner Luke Skywalker or Han Solo sound an optimistic note, as the late Judge Jerry Buchmeyer did in revisiting the issue of attorneys' fees - also referred to as lodestar, which consists of the reasonable hours expended multiplied by the reasonable hourly rate - in an employment case. Judge Buchmeyer indicated that, "armed with the plaintiffs' new filings, the Court shall once again attack the lodestar."24 At other times, judges can be downright bleak, as Justice Moore was when characterizing a case in which the parties had conspired "in a despicable scheme" to hide assets during divorce and child support proceedings.25 He wrote:

This case is somewhat akin to deciding a dispute between Darth Vader and the Borg, or if you prefer a classical metaphor, Scylla and Charybdis. There is no justice to be done here. . . . As much as we might prefer an outcome in which neither party profits from its wrongful conduct, it is not within our purview to do so. One of these undeserving parties, unfortunately, has to prevail.26And even the trial tactics of parties can elicit a Star Wars reference from a jaded jurist. In one case where a doctor was charged with enabling prescription drug abuse by allegedly issuing hundreds of medically baseless prescriptions for painkillers like oxycodone, the court chided the defendant for diversionary tactics.27 These tactics included demanding a list of a prosecution witness's published articles for the last decade, the cases in which the witness had testified, and a statement of the witness's compensation demands that the court noted were "[w]ithout citation to authority or much supporting argument."The judge said, "This diversion - the legal equivalent of Obi-Wan Kenobi's 'These aren't the droids you're looking for,' see Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope (Lucasfilm 1977) - is unavailing."28

Speaking of diversionary trial tactics, no discussion of Star Wars' influence on the legal system would be complete without a nod to what has become enshrined in the popular consciousness as "the Chewbacca defense." This legal "strategy," while inspired by the science fiction classic,actually owes more to the creators of South Park, where it appeared for the first time in the second season episode titled "Chef Aid." The Chewbacca defense refers to making a legal argument, the aim of which is to deliberately distract and confuse the jury with the use of a "red herring."29 In the episode, an animated Johnnie Cochraneis defending a record company being sued by the character Chef, who wants credit for a song he wrote. Cochrane distracts the jury with this soliloquy, which bears no relation whatsoever to the facts of the case:

Ladies and gentlemen, this is Chewbacca. Chewbacca is a Wookiee from the planet Kashyyyk. But Chewbacca lives on the planet Endor. Now think about that - that does not make sense! Why would a Wookiee, an 8-foot tall Wookiee, want to live on Endor, with a bunch of 2-foot-tall Ewoks? That does not make sense! But more important, you have to ask yourself: what does this have to do with this case? Nothing. Ladies and gentlemen, it has nothing to do with this case! It does not make sense! Look at me. I'm a lawyer defending a major record company, and I'm talkin' about Chewbacca! Does that make sense? Ladies and gentlemen, I am not making any sense! None of this makes sense! And so you have to remember, when you're in that jury room deliberatin' and conjugatin' the Emancipation Proclamation, does it make sense? No! Ladies and gentlemen of this supposed jury, it does not make sense! If Chewbacca lives on Endor, you must acquit! The defense rests.30Lest you believe that "the Chewbacca defense" exists only in pop culture as a synonym for distraction through reference to wholly unrelated people and events, it actually has transcended the world of viral videos and Urban Dictionary and has become immortalized in legal circles by the Supreme Court of Nevada, no less.31 In discussing an appeal of convictions for kidnapping and assault with a deadly weapon, the court points out in footnote 1 Willing's protests over the prosecution's characterization of his attempt to bring up information about the victim's supposedly wrongful conduct. The court refers to Willing's unsuccessful attempt at raising "a Chewbacca defense - the modern day equivalent of accusing the defense of raising a red herring."32 The court declined to consider Willing's claim, because (like all "Chewbacca defenses") it lacked "relevant authority or cogent argument."33

So whether you're channeling the wisdom of Yoda as you embark upon the litigation equivalent of attacking the Death Star, navigating your way through an asteroid field of murky contract provisions ("never tell me the odds"),or hoping to try a Jedi mind trick on a troublesome expert witness, remember that the Force will be with you, always. Just don't try the Chewbacca defense.

Notes

1. See, for example, Lucasfilm Ltd. v. High Frontier, 622 F. Supp. 931 (D.D.C. 1985).

2. In re Enron Corp. Securities, Derivative & ERISA Litigation, 235 F. Supp. 549

(S.D. Tex. Dec. 19, 2002).

3. Alman v. Reed, 2010 WL 4106686 (E.D. Mich. Oct. 7, 2010) (the opinion is silent

as to whether young prosecutor Skywalker ever whined about getting out of the

prosecutor's office and seeing the rest of the galaxy, or going to Toshi Station for

some power converters).

4. Martone v. Martone, 2009 WL 1662481 (Sup. Ct. Conn. May 19, 2009).

5. Edward Pekin v. Vito Parise, (Cir. Ct. Ill., Cook Cnty. Judicial Cir. Feb. 6, 2008)

(where the court duly notes that "Plaintiff makes the claim of loss of normal life

because he was an avid Star Wars fan and often dressed up as a Star Wars trooper

for various events." "Normal life," it would seem, is a very fluid concept).

6. People v. Hollis, 2009 WL 2248847 (Cal. App. 1st Dist. July 2009).

7. Totah v. Lucasfilm Entertainment Co., Ltd., 2010 WL 5211457 (N.D. Cal. Dec.

2010).

8. P.J. v. Review Bd. of the Indiana Dep't of Workforce Development, 2011 WL 6292202

(Ct. App. Ind.).

9. Roloff v. SAP America, Inc., 432 F. Supp. 2d 1111 (D. Or. May 26, 2006).

10. Id.

11. People of the State of New York v. Malcolm Harris, Docket No. 2011NY080152 (N.Y.

Crim. Ct. June 30, 2012).

12. Agrippa, LLC v. Bank of America, N.A., 2011 WL 102677 (S.D.N.Y. 2011).

13. Sierra Club v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 645 E.3d 978 (8th Cir. 2011).

14. Quinonez v. Empire Today, LLC, 2010 WL 5211501 (N.D. Cal. Dec. 16, 2010).

15. Smith v. Scribner, 2008 WL 649058 (C.D. Cal. 2008).

16. State v. Brown, 2007 WL 4555787 (Ct. App. Ohio Dec. 28, 2007).

17. Faith v. Clark, 2012 WL 2376327 (E.D. Cal. 2012).

18. The Pampered Chef v. Alexanian, 804 F. Supp. 2d 765 (N.D. Ill, July 14, 2011).

19. Robin Singh Educational Services, Inc. d/b/a Testmasters v. Blueprint Test Preparations,

LLC, 2013 WL 240273 (Cal. App. 2d Dist. Jan. 23, 2013).

20. Id.

21. United States v. Hodge, 558 F.3d 630 (7th Cir. 2009).

22. Id.

23. Commonwealth of Kentucky v. Marshall, 345 S.W.3d 822 (S. Ct. Ky. 2012).

24. Scribner v. Waffle House, Inc., 1998 WL 47640 (N.D. Tex. Feb. 2, 1998) (Judge

Buchmeyer even contrasted his own initially unsuccessful efforts with those of the

intrepid pilots of the Rebel Alliance, noting in a footnote that they had "conquer[

ed] the lodestar on the first attack").

25. Anthony v. Mazon, 2006 WL 1745769 (Cal. App. - 4th Dist. June 27, 2006).

26. Id.

27. United States v. Stapleton, 2013 WL 3967951 (E.D. Ky. July 31, 2013).

28. Id.

29. South Park, Episode 27, "Chef Aid" (Comedy Central, 2nd season).

30. Id.

31. Willing v. Nevada, 2013 WL 3297070 (Sup. Ct. Nv. May 14, 2013).

32. Id.

33. Id.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter