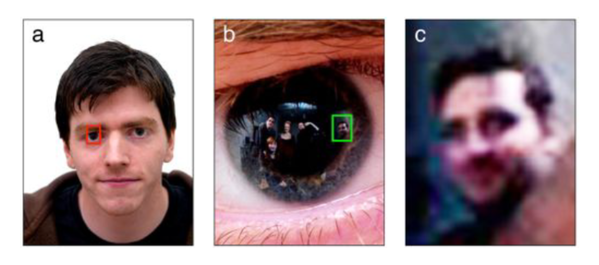

According to new research published Thursday in the journal PLOS One, high-resolution photographs can be "mined" for hidden information. Specifically, the authors said that photographs of faces can reveal enough visual information on bystanders to identify them.

In a small sampling of 32 study participants, test subjects were able to spot familiar faces reflected in the pupils of someone who was photographed 84% of the time, researchers said. When the reflected images were of unfamiliar people, observers were able to match the person to a second mug shot with 71% accuracy.

"Criminal investigations often use photographic evidence to identify subjects," wrote study authors Rob Jenkins, a psychologist at the University of York in England, and Christie Kerr of the University of Glasgow in Scotland.

"By zooming in on high-resolution face photographs, were were able to recover images of unseen bystanders from reflections in the subject's eyes.... For crimes in which the victims are photographed (e.g. hostage taking, child sex abuse), reflections in the eyes of the photographic subject could help to identify perpetrators," the authors wrote.

The study notes that the word pupil comes from the Latin word pupilla, which can mean young girl or doll, and conveys the idea that when one looks into someone else's eyes, they see a tiny doll-like version of themselves reflected back.

In the study, Jenkins and Kerr photographed eight individuals, who were themselves looking at four people who were behind the camera. Study subjects were asked to either match the images to a series of mug shots, or to identify people who were familiar to them in the eye reflections.

The study authors said that humans were extremely adept at identifying human faces, even if the images were very poor. In the portrait photographs, the person's face occupied about 12 million pixels, while the images of bystanders in the person's eye accounted for just 54,000 pixels, less than 0.5% of the portrait subject's facial area.

Jenkins, who studies facial recognition, described the portrait photographs used as passport-type photos. The authors noted also that there were limits to the forensic use of such photographs. Namely, they must be shot in high resolution and the subject must be looking directly at the camera.

"For now, our findings suggest a novel application for high-resolution photography: for crimes in which victims are photographed, corneal image analysis could be useful for identifying perpetrators," authors wrote.

for the bolded highlights in any color. Especially the last one in this article. Robots, photo forensics, facial recognition [Link], UAVs [Link]etc. etc. Humans made it. Humans can "brake" it.