The reversion of the 52-hectare parcel - an attractive hilltop overlooking the East China Sea - was supposed to be a sign of improved ties between the U.S. military and its Okinawa neighbors. But instead it has come to signify a problem that is increasingly straining relations in the prefecture: military pollution.

Seven years after the land at Nishi-Futenma was vacated, its future is still in limbo. The dozens of beige bungalows that used to house U.S. families are abandoned - their screen doors torn and walls overgrown with vegetation.

Under the SOFA, the Pentagon is not responsible for the remediation of land polluted by its bases in Japan. At the time the agreement was signed, environmental awareness was in its infancy and little understood was the contamination created as a byproduct of military operations - including fuel spills, runoff from industrial solvents and pervasive use of insecticides and herbicides.

Whereas other nations that host U.S. bases - including South Korea and Germany - have updated their respective SOFA agreements to bring them closer in line with current environmental concerns and make Washington more responsible for managing military pollution in their countries, the agreement with Japan has remained unchanged since 1960.

Although there are U.S. installations throughout Japan, the problem of military contamination is felt most acutely on Okinawa Island, where U.S. forces facilities take up approximately 20 percent of the land. Many residents blame the high concentration of military bases for creating overcrowded living conditions and congested roads. Okinawa, with a population of 1.4 million, is one of the few prefectures where the population has consistently grown over the past few decades.

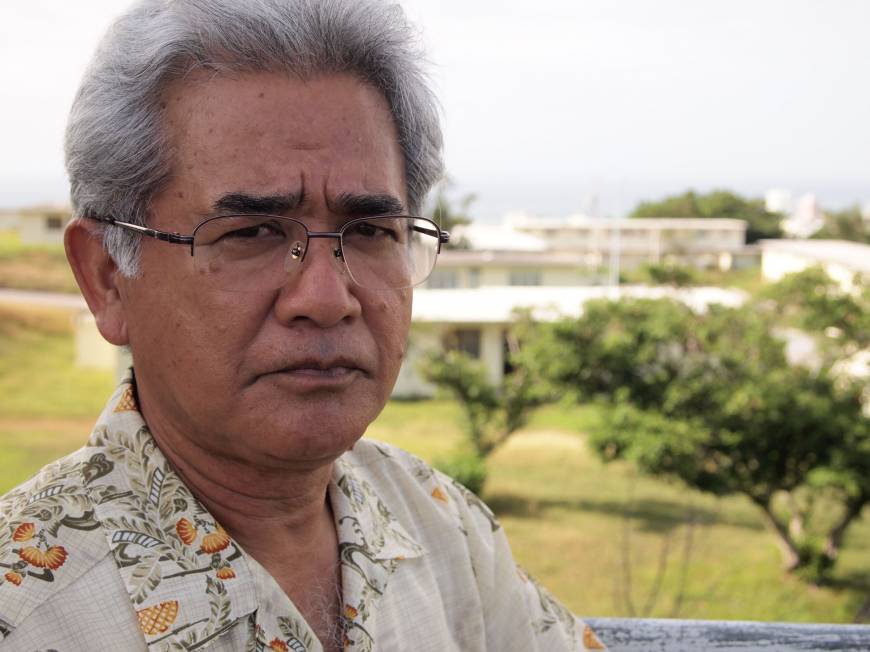

Arakaki explained that the land at Nishi-Futenma used to accommodate around 200 U.S. military families.

"In the future, it might be able to house 10 times that number of Okinawa families. But because of the worries about contamination, we still can't redevelop here. It's not fair," said Arakaki.

Arakaki has a personal connection to the land at Nishi-Futenma. Prior to World War II, his relatives' grave was located nearby, but during the 1950s, as the U.S. military forcibly expanded its bases on the island, the tomb - like those of many Okinawans - was built over.

During this period, when the island was dubbed the "Keystone of the Pacific," the military presence accounted for approximately half of Okinawa's economy. According to the prefecture's estimates, today it only contributes around 5 percent.

Recent projects to redevelop former military land have persuaded many Okinawa residents that their island can prosper without reliance on the bases. In Shintoshin, Naha, for example, the redevelopment of a former U.S. installation into a commercial district saw the area's revenue rise by a factor of almost 15.

However, the discovery of military contamination has delayed other attempts to rejuvenate the economy in the poorest prefecture. In the village of Onna, central Okinawa, high levels of mercury, cadmium and toxic polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) have hampered plans to redevelop military land returned in 1995. Meanwhile, authorities in the town of Chatan have recently been forced to postpone plans to widen roads onto former military land due to the discovery of dangerous levels of lead.

According to Arakaki, the issue that most highlights the risks of military pollution was the discovery in June of more than 20 barrels on a civilian soccer field built on former military land in the city of Okinawa. Tests on the barrels' contents revealed traces of herbicides and levels of dioxin in nearby water 840 times above safe limits.

Currently, the Okinawa Defense Bureau - the government's branch of the Defense Ministry on the island - is conducting further investigations to ascertain whether any more barrels are buried beneath the soccer field. According to local media, surveys have detected about 20 spots where containers may still lie. However, last week the work was temporarily halted when a Self-Defense Forces bomb team had to be called in to dispose of a U.S. hand grenade discovered 60 cm beneath the surface.

In October, the prefectural government announced the formation of a new department with a remit to deal with issues related to contaminated military land. Scheduled to start operations in April, it seems the department will soon have its hands full. In the coming years, Washington and Tokyo plan to release more military land to civilian control, including the Makiminato Service Area - a sprawling 270-hectare installation that used to serve as the U.S. military's main supply depot on the island - and, eventually, the 480 hectares of troubled Marine Corps Air Station Futenma.

"As more and more (former base) land is scheduled to be returned, it will be increasingly important to know how the land was used by the U.S. military - including what kind of substances they stored and used there. With this information, we can initiate any necessary cleanup plans," explained Arakaki.

The chairman also detailed one more factor motivating the prefecture's decision to create its specialized pollution division: If environmental investigations are left up to the central government, he believes, the true levels of pollution might be concealed.

According to Arakaki, the defense bureau does not routinely reveal pollution findings to the prefecture and, in the case of the barrels unearthed in the city of Okinawa, it downplayed the discovery of dioxin.

"Perhaps Tokyo does not want to reveal the true extent of the burden of military bases on Okinawa. That is why we must work assiduously on the issue of contamination," said Arakaki.

Diego Garcia in the Indian ocean is being treated like a toilet...and that is an understatement.