© Jacqueline Girard

What was Dr. Bridget Buxton's secret to solving the mystery of the "the lost eagle?"

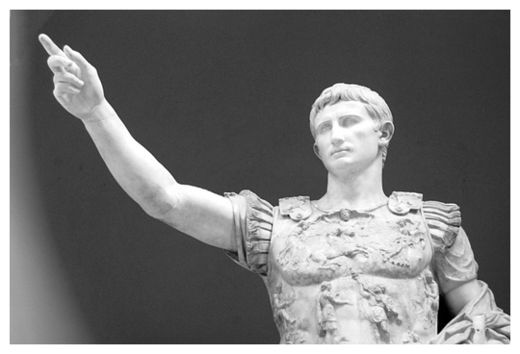

Google images. Buxton, on behalf of the Archaeological Institute of America, presented her lecture to an audience of Assumption students, faculty and staff on Monday, September 16. The lecture was an interpretation of Rome's most famous statue, the Prima Porta Augustus. The statue presents the first emperor of the Roman Empire as "a symbol of western self control and excellence versus the great enemy in the east," said Buxton. Since it was discovered in the outskirts of Rome in 1863, historians and archaeologists have attempted to match the story that is carved out on the statue to the historical accounts that exist.

However, "the correct interpretation that we've had for the last one hundred and fifty years is actually wrong," Buxton argued. Buxton began by presenting to her audience the original interpretation of the statue. The marble statue, which seems to be carved into what can be interpreted as a storyboard, references significant historical events in the history of the Roman Empire.

The center of Augustus' cuirass (chest plate) depicts the surrender of an eagle, which in Augustus' time, was a legionary military standard. Eagles were prized possessions of each Roman legion, a symbol of victory and strength in war and conquest.

Buxton laughed as she attempted to illustrate what would be the modern equivalent. "[It would be like] if somebody came in and stole the [Assumption] greyhound, that would be bad, right?" The audience responded with laughter.

On the front of the cuirass "a figure, who is obviously a barbarian, is handing one of these eagles to a figure who is a Roman" is carved in marble. The historical account associated with this representation begins with the first Roman Triumvirate, which consisted of Pompeius Magnus, Julius Caesar and Marcus Crassus. In an effort to prove his superiority over the others, Crassus left Italy to conquer the barbarians (Parthians) in the Middle East. Unfortunately, the Parthians destroyed Crassus' legions. He was killed, and the eagles were captured. Following his defeat, several Roman legions went out to avenge Crassus and, they too, were defeated and more eagles were captured.

In 20 B.C.E., Emperor Augustus approached the Parthians, bargaining to get the eagles back. He succeeded and returned to Rome in glory.

"In the surviving Roman literature we have the celebration of these bloodless victories over Parthia, the peaceful return of the eagles, the superior Western forces defeating the decadent and evil eastern menace. This is a very persistent thing we have in the texts from the Augustan age, so it profoundly effects the way we look at this statue," said Buxton.

Naturally, when the statue was recovered in 1863, because of the eagle, historians and archaeologists connected the image on the statue to what is written in Roman literature. Buxton, however, argues that the image on the Prima Porta is representing another historical event entirely.

The first clue, which led Buxton to question the accuracy of the story being told on the Prima Porta, was the research of her colleagues.

"Look at that central armored figure on the cuirass, which has always been identified as a Roman soldier and look specifically at it's buttocks and the curve of it's thigh and you see it is in fact a female," Buxton said.

Now, this leads the identity of the "barbarian" to the right of the woman into question.

"Look at the costume. It could be an eastern barbarian but if you look at the tunic and baggy trousers, his bare head, the short beard, these looks are hardly exclusive to Parthia, you can see very similar representations of Western European barbarians," said Buxton.

So, if the figure on the left isn't a Roman soldier, but a woman, and the figure on the right isn't a barbarian, but an unidentified Western barbarian, then what is this cuirass illustrating?

Here's the crucial clue that helped Buxton crack the code of the Prima Porta: the dog that is accompanying what used to be identified as a Roman soldier, but is now speculated to be a woman.

"This whole lecture depends on that little dog there. We cannot ignore or underestimate the importance of this little dog, everybody does so," emphasized Buxton. The dog serves as "a symbol to help us identify the being that it accompanies," she adds.

Who is the mystery woman with the dog? Buxton revealed it is the goddess Nehalennia, who is more central to Germanic culture. When asked how she was able to identify the goddess, Buxton said, "Google Images."

There is much more detail to the story, which led Buxton and her colleagues to attempt to write the story that was being told on the cuirass "for the first time." So now, in addition to the Roman written history of the lost eagles, there is an entirely new historical account of what is really on the front of the Prima Porta Augustus. Buxton emphasizes "how blinded we are by our surviving texts" and how most historians try to fit the evidence and artifacts to whatever historical accounts are available. Buxton's theory just goes to show how a simple detail, a curve of the hip, a wave in the hair, even a dog, can rewrite history.

"how blinded we are by our surviving texts" and how most historians try to fit the evidence and artifacts to whatever historical accounts are available."

Isn't that 'to the victors go the spoils'? And one of those spoils is to control the historians et al that follow in your wake.... on your payroll of course.

Too bad a pic of the stature in question of the dog and two figures wasn't available.