Children have witnessed massacres, mothers seen their sons killed, families watched their homes looted and burned. But there is one act of violence that refugees from the Syrian crisis will not discuss.

The conflict has been distinguished by a brutal targeting of women. The United Nations has gathered evidence of systematic sexual assault of women and girls by combatants in Syria, and describes rape as "a weapon of war". Outside the conflict, in sprawling camps and overloaded host communities, aid workers report a soaring number of incidents of domestic violence and rampant sexual exploitation.

But this is a deeply conservative society. The endemic violence suffered by Syrian women and girls is hidden under a cultural blanket of fear, shame and silence that even international aid workers are loth to lift.

Dr Manal Tahtamouni is the director of the Institute for Family Health, a local NGO funded by the European commission that was among the first to open a women's clinic in Zaatari refugee camp. When asked, she says, most women will not admit to being raped. They will say they have seen others being raped.

"This is a conservative area. If you have been raped, you wouldn't talk openly about it because you would be stigmatised for your entire life. The phenomenon is massively under-reported," Tahtamouni says. Only after a long process of building trust through one-on-one counselling sessions might a rape survivor talk. Of the 300 to 400 cases her clinics receive in a day, 100 are female victims of violence, mostly domestic.

In the day, the camp bristles with the economic and social buzz of a resilient society attempting to reclaim normality. Under the broad blue skies of the Jordanian desert, groups of women in full black veils peaked with sun visors shop in a makeshift high street of UN tents. At night, when gun battles raging at home can be heard across the border, the atmosphere darkens.

Even "Abu Hussein", a local boss of Zaatari's brothel and bar district, has requested that UN officials launch patrols to control gangs of young men wreaking havoc in the camp and harassing women. Groping and lewd name-calling during food distributions and in the public latrines are common. Rapes have been reported."There is a tendency to think that once [women] have crossed the border, they are safe," says Melanie Megevand, a specialist in gender-based violence at International Rescue Committee charity. "But they just face a different violence once they become refugees."

In a reversal of the cultural norm, many families here are headed by women. Fathers and husbands have either been killed or gone to fight. At least three-quarters of these families don't live in Za'atari camp but in nearby towns, where they quickly disappear beyond the reach of aid workers and their resources. With no means to support themselves, they are vulnerable.

Um Firas has lived in Mafraq, near Zaatari, for more than a year since escaping Homs. She rarely leaves her home. Her husband disappeared years before the war so she is alone, accumulating an enormous debt to cover her rent. She still believes her family is better off in debt than inside the camp.

She is particularly concerned for her teenage daughter, who took to sunbathing until her skin burned in Syria. "She told me, 'If I turn black, the Shabiha [pro-government militia] might not want to rape me," she says. "They were targeting women. Iranian and Hezbollah fighters came into our neighbourhood with their swords drawn. The women they found, they raped. They burned our homes," she adds, too exhausted by grief to stop crying.

"I saw maybe 100 women stripped naked and used as human shields, forced to walk on all sides of the army tanks during the fighting. When their tanks rolled back into the Alawite neighbourhood, the women disappeared with them."

In Mafraq, her landlord wants to evict her. He had offered to let the family stay only if Um Firas allowed his 28-year-old son to marry her 16-year-old daughter. Beautiful young Syrian women are in high demand. She refused.

The Rev Nour Sahawneh leads the community effort to help refugee families in Mafraq. He has noticed with alarm a growing number of men flying in from the Gulf states to take Syrian girls from their desperate families.

"Their pale skin, the way they talk, cook - it's a fantasy for them, even if she is only 14," Sahawneh says.

"Yesterday I heard a man I know accepted 9,000 dinars [£8,420] from a Saudi guy for his 15-year-old daughter. He will take his 'wife' to a flat and stay with her for a few months then go home without her. It's illegal to marry women under 18 in Jordan. Saudi men cannot marry non-Saudis without permission. She is not a wife but for sex only."

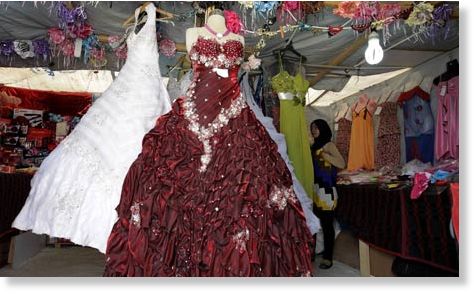

In the past three months, a bridal boutique has sprung up in a small tent in what residents ironically call Zaatari's Champs Élysées. It offers a choice of six elaborate, bedazzled bridal gowns to rent for 2,500 Syrian pounds (£15.80). The average age of the wearer is 15.

Rihab, 19, is marrying her 27-year-old camp neighbour tomorrow. Five months ago she met his sister, who made the match. Surrounded by the groom's female relatives and shaking with nervy excitement, Rihab strips out of her niqab to try on the strappy dress only her husband will see her in.

Her family had refused the marriage initially, the boutique owner explains under her breath. It's going ahead now only because the groom's family have arranged for the new couple to be "bailed out" of Zaatari to start a new life in Jordan. Jamilla, Rihab's future mother-in-law, looks on, pleased. She married her 15-year-old daughter to a man in Amman last year and already has a one-year-old grandchild.

"Isn't it better that they are married, that she is protected by her husband? I am marrying off my daughters as quickly as I can. They are young. They don't know any better," she says with a laugh.

There is no time to ask how the bride is feeling. The dress has been bagged and she is being hurried out into the bustle of the camp. As her veil falls back over her face it covers a startled, wide-eyed expression of excitement - or fear.

"According to AlDiyar newspaper, an international gang started buying children from Syrian families. Families who escaped terrorism in Syria to Greece, Cyprus or Turkey. The children are later taken to Europe where they’re to be sold. Children’s description, photos and blood type were posted on some websites. 100,000 Iraqi kid were sold in the Arab Gulf countries and Qatar. This is where the article ends.

Human trafficking had benefited immensely from the “Humanitarian Wars”, as did Organs Trade. Why else would the blood type be included, are the Syrian children’s organs being harvested?

This organ trade is horrific and with the children they get three uses--(1) $$ for child porn (2) $$ for child porn snuff and (3) when they kill the children and then they can sell their organs." [...]

Organ Trade in Syria, FSA Delivers and Turkey Butchers [Link][Link][Link][Link]

Testimonies of the Syrian organ trade in Turkey kidney price of $ 6000 https://fr-fr.facebook.com/video/video.php?v=478302042240987 [Link]

Turkish Authorities Involved in Stealing Body Organs of Injured Syrians [Link][Link]

Syrian organ traffickers are backed by Western organizations - official [Link]

Where organ traffickers and criminal doctors become heroes: Enter the Washington Post [Link]