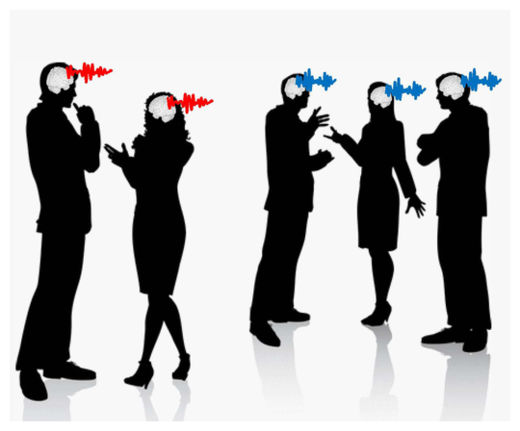

Studying the infamous "cocktail party problem," researchers found that brain waves are shaped to allow the brain to track the sounds it's interested in while ignoring competing sounds. The findings could be used to aid people with problems hearing or focusing on sounds, linked to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism and aging, researchers reported March 6 in the journal Neuron.

Humans don't have a way of closing their minds to sounds, and so the brain "hears" everything that reaches a person's ears. The new study confirmed this.

"We also provide the first clear evidence that there may be brain locations in which there is exclusive representation of an attended speech segment, with ignored conversations apparently filtered out," senior author Charles Schroeder, a neuroscientist at Columbia University, said in a statement.

In the study, the researchers recorded the brain activity of epilepsy patients, who had recently undergone surgery, as they listened to natural spoken sentences. In order to figure out how the brain ignored or focused on various sounds, the researchers showed the patients two side-by-side videos of people talking, and told them to pay attention to one of the speakers.

In the brain's auditory cortex, which processes incoming sound signals, the brain activity represented both the speech being attended to and that being ignored, but the attended speech had stronger signals.

In higher-level processing regions responsible for things like language and attention control, only the attended speech had a detectable, clear representation, the results showed. That representation became more refined as a sentence progressed, suggesting as a cocktail-party conversation continues, the brain focuses more and more only on those sentences while tuning out others.

Previous studies of the cocktail party problem have used simplified, unnatural sounds such as beeps or brief phrases, Schroeder said, whereas this study used natural speech.

The ability to study widespread patterns of brain activity in surgical epilepsy patients provides a link between work on a "brain activity map" in animals and uniquely human abilities like language and music, the researchers say.

Zeroing in requires binaural hearing.

I'm stone cold deaf from my right ear. Hearing from my left ear is just fine; people don't have to raise their voices, for instance.

However, I can't tell the direction of sounds. If I am in the hallway between my front door and my back door, and someone knocks on one of the doors, I have only a 50-50 chance of going to the correct door.

If I am in a room -- especially one that is acoustically live -- and more than one person is talking, I can't understand what any of them is saying. I have to stop them with, "Please -- just one person at a time."