Bad news and good news re this paper. Bad news is that I haven't posted on it in two years - good news is that it's been so long the full text version of it is now available free.

Before we get into the paper, which studies the consumption of kangaroo, just to get us all in the mood, I'm going to put up a quote from The Protein Power LifePlan. I had to fight our editor tooth and nail to keep these few paragraphs in the book. She thought they were too gross for the average reader. The quote comes from the records of an 1948 expedition to Arnhem Land, a remote part of of the Northern Territory of Australia set aside for the "use and benefit of the aboriginal inhabitants of northern Australia." It's about how the indigenous Australians cook and eat a wallaby.

A large fire was made in a depression in the sand, and stones and shells were heated. Small green branches were placed on top of the stones and the wallaby was flung on these. After 5-10 minutes it was taken off the fire, placed on a layer of green leaves, and the singed fur was removed with a tomahawk. [Just the fur, not the skin.] Although the women sometimes did this preliminary treatment, a man always did the subsequent cutting up, which was done with a metal spear blade.I'm reasonable certain this method of wallaby preparation has been in use since man first occupied Australia. It is probably a pretty fair description of how all game animals were cooked in ancient times. And it leads us into our discussion of the a paper on old foods vs new foods. But first, let's talk a little about food and inflammation.

The first cut was made horizontally on the ventral [belly] surface at the level of the anus, and next on the dorsal [back] surface along both sides to sever the leg muscles. Another cut was then made from the anus to the neck. The viscera were pulled out; and the kidneys, liver, heart and lungs, and the omental and mesenteric fat [the fat surrounding the intestines] were separated from the rest, and cooked on the hot stones and coals for 5 minutes. The cooked lungs were used to soak up the blood inside the carcass and then eaten. The offal was regarded as a delicacy by everybody and a certain amount of squabbling always followed its distribution.

The tail was cut off, and during the cooking was put on or alongside the body. The carcass was laid flat, dorsal side downwards, on the hot stones and ashes and the body cavity was filled with hot stones. Sheets of paperbark formed a cover over the animal, and sand was scooped out to make an oven. Wallabies weighing 15-20 pounds were cooked for 25-35 minutes. Everything edible was eaten except the stomach and intestines. The skull was cracked open to get the brain, and the bones were broken to extract the marrow.

We require both food and oxygen to sustain life, yet, in a bizarre twist of fate, both of these necessities slowly kill us.

Slings and arrows in the form of free radicals accrued from a lifetime of breathing gradually dent and ding our mitochondria to the point that more and more of of them give up their ghosts until we, deprived of enough functioning cellular furnaces, follow suit.

Same thing happens with food albeit via a different mechanism.

As I contemplated one early morning in Rome a few years ago, food is inflammatory. And too much food weighs a body down with not only adiposity but with excess inflammation as well.

I would like to be able to say that carbohydrates are the only drivers of inflammation, but, sadly, that would not be true. All food intake stimulates inflammation. Although the weight of the research evidence seems to tip the scales in favor of carbs promoting more than non-carbs, all food is guilty.

It's difficult to limit the amount of free radical damage as a consequence of breathing by trying to breathe less. We can't go on an intermittent breathing regimen as we can an intermittent fast, so we're pretty much stuck with breathing about 20 times per minute. But we can change our food.

The question then becomes, What kind of a diet generates the least inflammation?

To answer that question, we need to know how food provokes inflammation.

For the most part, the proteins in food are the culprits. Carbohydrates are not proteins, they stimulate inflammation differently. Carbohydrates in the diet end up as glucose in the blood. Glucose in the blood is kind of like oxygen - it's a requirement for life, but we don't want too much. Even a normal level of blood sugar is a little corrosive, but when levels are high for sustained periods, much more damage ensues.

Almost everything that gets our immune systems fired up is a foreign protein. The body is always on the lookout for foreign proteins, and when it encounters one, the immune system rallies and mounts an effort to get rid of it.

What's a foreign protein? Any protein the body doesn't recognize as self. Other than in cases of autoimmune diseases in which the body's immune system turns on one or more of its own proteins, the body pretty much recognizes itself as non-foreign. But, proteins coming in from outside the body are foreign. Proteins in food are definitely foreign.

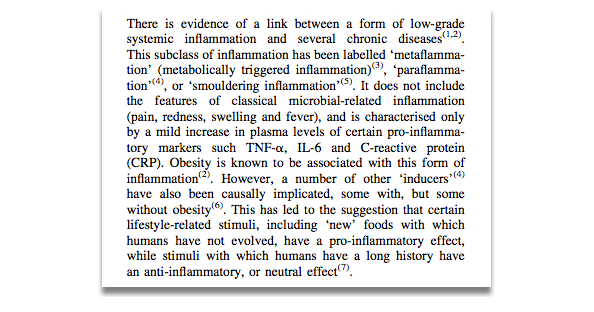

But there are degrees of foreign. Less-foreign proteins stimulate less of an immune response than do more-foreign proteins. What makes a protein more or less foreign? In general, our immune systems' familiarity with it. Foods we have consumed for millennia are more familiar. People who had problems with those foods tended to die out, while the ones who didn't have problems tended to flourish and reproduce more. In the end, those of us here now are the beneficiaries of the forces of natural selection and should have fewer inflammatory problems with food proteins that have been in the diet since prehistoric times. At least that's an hypothesis. (It's the hypothesis of Dr. William Davis, author of Wheat Belly (my review here), who believes that the new dwarf wheat, which has only been around for about 50 years, causes vastly more problems than the older versions of wheat that humans have consumed since Biblical times. The proteins in the new wheat are different than those in the old.)

Problem is, how do we test this hypothesis?

One way would be to take a genetically homogeneous group of people, present them with a food they've eaten forever, measure the inflammatory response and compare it to that provoked by a modern version of the same food.

This is how the researchers did it in this paper. Here is how the authors' start out with a pretty good description of the notion of newer vs older foods as inflammation inducers.

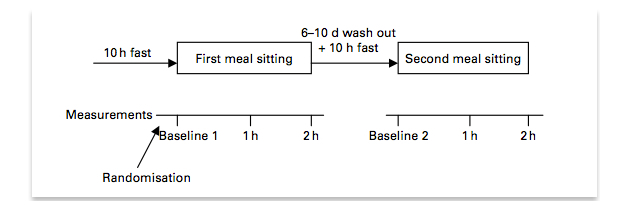

The researchers recruited ten healthy native Australian subjects (six male, four female), all with normal body weights and no history of any metabolic disorders or prescription drug use. These subjects were divided into two groups and fed a diet composed of loin steak (100g) from either kangaroo or wagyu beef, baked potato (75g) and green peas (50g). (Kangaroo has been a part of the traditional Aboriginal diet in Australia, while wagyu beef is a breed of newly hybridized domestic beef.) This study was a cross-over study so that all the subjects ended up being their own controls. The feeding schedule is shown below:

The subjects provided blood samples just prior to each meal and hourly for two hours after each meal. The samples were tested for serum triglyceride levels and for levels of the inflammation indicators TNF-α, IL-6 and C-reactive protein.

What was the outcome?

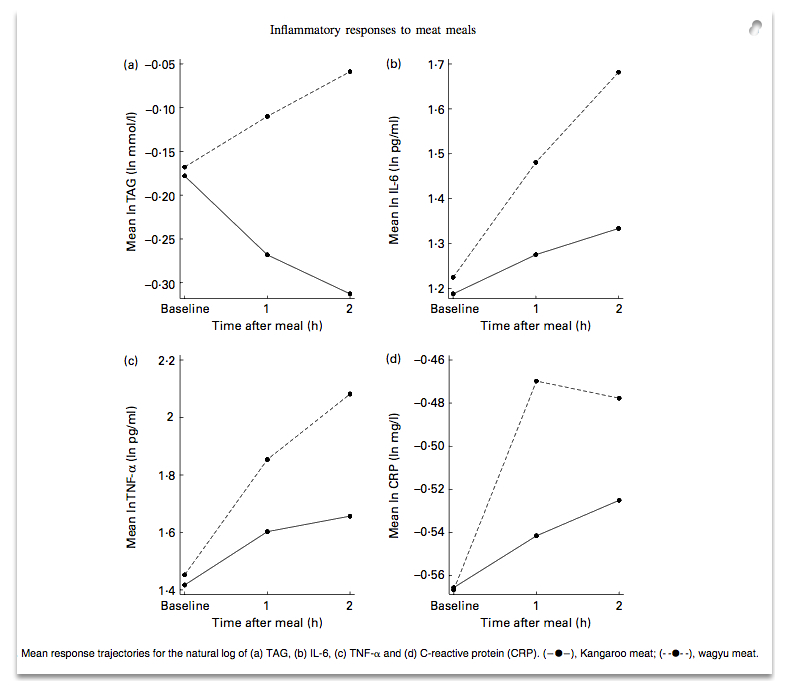

Blood from the subjects consuming the meal with kangaroo showed a significant increase in the levels of TNF-α and IL-6, a non-significant rise in C-reactive protein and a drop in triglycerides. This isn't surprising because, as I mentioned earlier, all food is inflammatory.

The subjects who ate the wagyu beef experienced a greater increase in TNF-α and IL-6 along with a significant increase in C-reactive protein and triglyceride not seen in those consuming the kangaroo.

As the authors concluded

Our findings show that a 'newly' introduced form of beef (wagyu) has a significantly greater postprandial [after eating] inflammatory effect than a traditional kind of meat (kangaroo).Here is the abstract of the paper:

This is only one paper, with a small sample size, and is the only paper like this I've seen. I would like to see more work done in this area. It would be nice to know, for example, how long this inflammation lasts past the two hour window. It would be of great interest to see what happens if these meals are followed for a couple of days of meals instead of just one meal. And it would be nice to see what would happen if the two meals were isocaloric, i.e., contained the same number of calories. These meals both contained 100 g (about 3.5 ounces) of meat, but the wagyu beef has a much, much higher fat content (25%-30% fat) as compared to the kangaroo (~4% fat). Since the wagyu meat is so much higher in fat content, 100 g of it will provide way more calories than 100 g of kangaroo. For all anyone knows, it was the extra calories causing the uptick in the inflammatory markers and not the difference in new vs old food. We just don't know from this study.

This isn't a perfect study, but it is a start. It is, after all, called a preliminary study in the title. What it does provide is a nice foundation for this research group or another to do a more in-depth evaluation.

Coming from South east Europe from the less developed ex communist countries that were still using oldfashioned ingridients and methods of cooking, I had serious problems adjusting to the UK food, I lost initially a lot of weight as I just couldn't find anything I liked and the bread was not filling me. Later when I started to get used to it I began to put on too much weight until 2 years ago when I started to have serious health problems and develop an autoimmune desease. Last summer I went back home and spent for the first time 2 months there, eating Mediterranean diet, the food my great grand parents have thrived on for centuries. I completely recovered and don't even get the sniffles nowadays. I shall do that once a year from now on.

On the contrary to the ideas propagated on sott about the evil wheat and carbohydrates, this article proves that there is only one right approach in order to decide if you should eat a particular food: Ask yourself has your grandmother eaten it?