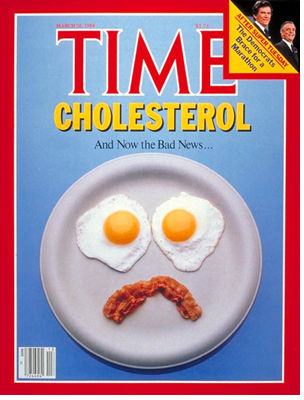

One of the major players in bringing cholesterol to the public's awareness was Time magazine. Its piece on cholesterol in the March 26, 1984 issue was a devastating hit piece on both dietary cholesterol and dietary fat. Both - the article explained - were a main driving force behind the development of heart disease.

Reading this article today, it's amazing how it drips with misinformation. At the time, however, most people - physicians included - accepted it as gospel. Sadly, even today, many physicians who should know better believe in and act in accordance to the bountiful misinformation contained in this piece.

I could write a blog longer than the article (and it's a long article) describing and dissecting all the many errors, but I'm going to go over just one. And that one just briefly. But before I get to that, let me show you just a few of interesting small parts of the article beginning with the very first sentence:

Cholesterol is proved deadly, and our diet may never be the same.Hmm. Dietary cholesterol has been proved pretty benign. But the writers are correct about our diet being changed.

And take a look at this:

For decades, researchers have been trying to prove conclusively that cholesterol is a major villain in this epidemic [heart disease]. It has not been easy.Have you ever seen a better example of the confirmation bias at work. We know cholesterol is a problem, and we're going to prove it no matter what it takes. So what if the evidence keeps blowing up in our faces, if we work hard enough, we can by God prove what we know to be true.

Although most cholesterol found in the body is produced in the liver, 20% to 30% generally comes from the food we eat.Actually, the figure is about 15 percent that comes from the food we eat. Most cholesterol is made in the liver, but not all. Virtually every cell in the body has the ability to make cholesterol, because it is so important to survival.

The main thrust of the article is about a study demonstrating that lowering cholesterol levels brought about a decrease in cardiac death rate. Here it is presented in the breathless prose of the Time writers:

That was the reason for the N.H.L.B.I, study. The elaborate, ten-year program recruited 3,806 men between the ages of 35 and 59, all of whom had cholesterol levels above 265 mg per deciliter of blood (the average for U.S. adults is 215 to 220). Half the men were put on daily doses of cholestyramine, an unpleasant, cholesterol-lowering drug that was mixed with orange juice and taken six times a day. One participant likened taking it to swallowing "orange-flavored sand." Among its side effects: constipation, bloating, nausea and gas. The other half received a similarly gritty placebo. Researchers had decided to use a drug rather than diet to lower cholesterol, because it would have been virtually impossible to control or measure the diet of so many men over so long a period. By the end of the study, the cholestyramine group had achieved an average cholesterol level 8.5% lower than that of the control group and had suffered 19% fewer heart attacks. Their cardiac death rate was a remarkable 24% lower than that of the placebo group.Pretty powerful stuff, you might think. Which is just what the authors of this article must have wanted you to think. After all, a failed study doesn't produce cover stories.

The lesson is plain, says Dr. Charles Glueck, director of the University of Cincinnati Lipid Research Center, one of twelve centers that participated in the project: "For every 1% reduction in total cholesterol level, there is a 2% reduction of heart-disease risk." This, says Project Director Basil Rifkind, is the evidence scientists have been waiting for. "It is a turning point in cholesterol-heart-disease research."

There are more than a few flies in this anti-cholesterol ointment, however. Let's take a look at what Gary Taubes writes about this study in Good Calories, Bad Calories:

In January 1984, the results of the trial were published in The Journal of the American Medical Association. Cholesterol levels dropped by an average of 4 percent in the control group - those men taking a placebo. The levels dropped by 13 percent in the men taking cholestryramine. In the control group, 158 men suffered non-fatal heart attacks during the study and 38 men died from heart attacks. In the treatment group, 130 men suffered non-fatal heart attacks and only 30 died from them. All in all, 71 men had died in the control group and 68 in the treatment group. In other words, cholestryramine had improved by less than .2 percent the chance that any one of the men who took it would live through the next decade. To call these results "conclusive," as the University of Chicago biostatistician Paul Meier remarked, would constitute "a substantial misuse of the term." Nonetheless, these results were taken as sufficient by Rifkind, Steinberg and their colleagues [those who had been searching for 'proof' for decades that cholesterol causes heart disease] so they could state unconditionally that [Ancel] Keys had been right and that lowering cholesterol would save lives.Aside from the lack of any real meaningful data, the authors tried to palm off what they had found from a drug study as being applicable to diet. Again, from Good Calories, Bad Calories:

Pete Ahrens [a cholesterol researcher at Rockefeller University] called this extrapolation from a drug study to a diet "unwarranted, unscientific and wishful thinking." Thomas Chalmers, an expert on clinical trials who would later become president of the Mt. Sinai School of Medicine in New York, described it to Science as an "unconscionable exaggeration of the data." In fact, the LRC investigators acknowledged in their JAMA article that their attempt to ascertain a benefit from diet alone had failed.But that certainly didn't keep them from trying.

Although there were several people mentioned in the Time article who were examples of the benefits of healthful, low-fat living, the star of the piece had to be Fred Shragai.

Fred Shragai, 59, of Encino, Calif., is a good example. Fourteen years ago, the prosperous real estate developer had a cholesterol level above 300 mg. At the time, he smoked four packs of cigarettes a day, was overweight (202 lbs. on a 5-ft. 5-in. frame) and routinely put in five or six 14-hour, pressure-packed days a week at the office. Rich sauces and fatty meat were his standard fare for both lunch and dinner, and exercise meant reaching under the bed to grab from his stash of pretzels and potato chips. Shragai was a classic candidate for a heart attack, and at the age of 45, he had one. Nine years later he was hospitalized for an operation to bypass five seriously blocked coronary arteries. In desperation, Shragai enrolled himself in U.C.L.A.'s Center for Health Enhancement. By changing the way he lived, he was told, he could lower his cholesterol level and reduce his risk of another heart attack.Do a little Googling on Fred Shragai and a few things turn up. Apparently, Mr. Shragai, a Holocaust survivor, was quite an interesting character. In addition to being a successful businessman, he donned a Santa suit and entertained children around Christmastime. As described in a December 1990 article in Orange Coast Magazine,

There was much to learn. Cholesterol, as Shragai found out, is packaged by the body in envelopes of protein, and only some of these packages are potentially harmful. The main culprit, LDL (for low-density lipoprotein), is the body's oil truck, circulating in the blood, delivering fat and cholesterol to the cells. Studies have shown that the higher the level of LDL, the greater the risk of atherosclerosis. Another type of cholesterol package is called HDL (for high-density lipoprotein). It appears to play a salutary role, helping remove cholesterol from circulation and reducing the risk of heart disease. Shragai's goal was to lower his level of LDL and raise his HDL.

Diet was a first step. To begin with, such cholesterol-rich foods as eggs and organ meats and most cheeses can directly add to the level of potentially harmful LDL. Fat has an even bigger impact, although the reasons are not well understood. Saturated fat tends to raise LDL levels. Butter, bacon, beef, whole milk, virtually any food of animal origin is high in saturated fat; so are two vegetable oils: coconut and palm.

Polyunsaturated fats, which are typically of vegetable origin, have the opposite effect; thus corn, safflower, soybean and sesame oils tend to lower the level of potentially dangerous LDL. Fish oils do the same. In the middle are the mono-unsaturated fats such as olive and peanut oils. These may lower LDL slightly, but tend to be neutral.

The amount of fiber in the diet also seems to influence cholesterol levels. "LDL cholesterol can be reduced 20% in people with high levels just by consuming a cup of oat bran a day," says Dr. Jon Story of Purdue University. However, Story adds, "that does not mean you can go and eat whatever else you want."

For reasons that are still under study, cholesterol levels are influenced by a number of life-style factors. For instance, regular exercise can significantly raise the level of protective HDL. Alas, a couple of push-ups a day will not do the trick, says Dr. Josef Patsch of Houston's Baylor College of Medicine: "You need sustained aerobic exercise for 20 minutes at least four times a week to really benefit." A less strenuous way to raise HDL levels may be to have a daily shot or two of alcohol. "The evidence is indirect," reports Epidemiologist Stephen Hulley of the University of California at San Francisco, "but social drinkers have HDL levels as much as 33% higher than those found in teetotalers." On a more sober note, U.C.S.F.'s Dr. Richard Havel warns: "Anyone who recommends raising HDL by drinking is playing with fire." Stress too has a detrimental effect. Studies have shown that the cholesterol levels of medical students peak at exam time, while accountants hit their high point around April 15.

By applying these lessons, says Shragai, "my life was totally changed." Today the man who used to love steak says, "I won't touch it." At a restaurant, "if I choose fish, I ask the chef to skip the butter or please to sauté it in wine." Every morning, regardless of weather, the man who once spurned exercise goes for an eight mile, two-hour hike through the wooded mountain trails near his home. He no longer smokes. His workdays average between eight and ten hours, but he insists, "I can absolutely stay away from the tension now. If I feel the pressure, I take off. Business associates get used to it; I set my own pace." Shragai no longer lives in fear of a sudden heart attack: his blood pressure and pulse rate are down, and most remarkable, his cholesterol level has dropped to an exemplary 195.

Shragai, in his late 60s, stands 5 feet 5 inches and weighs 165 pounds, down from his former rotund 200-plus since the doctor put Santa on a diet. His beard and twinkling blue eyes are his own, he says proudly.The article describes Mr. Shragai's joy in his long-term job as Santa to many of his area's poor residents. He would visit houses, tell stories and bring presents.

"I'll do this as long as I possibly can," Shragai says, his eyes twinkling behind his Santa glasses. "After all, Santa can't just quit."Unfortunately, that wasn't all that long. Mr. Shragai died of a heart attack about two months later on Feb 8, 1991 at age 66.

You can read about his life in an article in the Guardian written by his daughter as she came to grips with his death.

Many people who were in Mr. Shragai's condition - overweight, overworked and overfed - bet their lives that the promise made by the Time article would be fulfilled. If they quit smoking, cut the fat from their diets, took up exercise and dropped their cholesterol levels, they would avoid an early death from heart disease. As the Time article said about Mr. Shragai:

[he] no longer lives in fear of a sudden heart attack: his blood pressure and pulse rate are down, and most remarkable, his cholesterol level has dropped to an exemplary 195.As if these changes undo the risk of heart attack. We can see from Mr. Shragai's unfortunate case that they don't.

Basically, he bet his life - literally - on the recommendations of doctors who were responsible for most of the hype in the Time article. It's hard to say whether he won, lost or broke even on the bet, because we don't know what the outcome would have been had Mr. Shragai continued on his previous path. Or what would have happened had he gone on a low-carb diet instead. Based on my years of experience, I would bet that he would have done better on the low-carb approach, but, as I say, there is no way to know for sure.

There are a couple of take-home messages from Mr. Shragai's case. The first is that we don't really know what constitutes true risk for heart disease. Reduction of blood pressure, weight and cholesterol levels - measures of risk in the estimation of most physicians - didn't prevent a disastrous outcome. The second, and, in my view, the most important is that when we make nutritional and lifestyle decisions, we are betting our lives that we've made the correct decision. Even those maintaining their course are making the decision not to change. Decisions precede actions, and actions definitely have consequences, which means decisions have consequences.

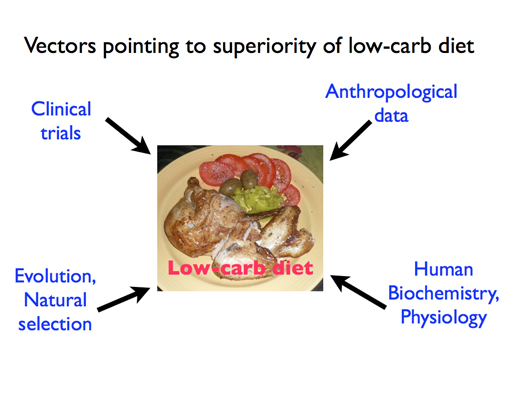

I'm betting my life that saturated fat is good for me and that carbs are bad. I eat a ton of saturated fat and very few carbs (unless I'm being a very bad boy as I was last night when I indulged in some of my granddaughter's birthday cake). So, if Dean Ornish is right and I'm wrong, I could be in deep trouble and maybe live a dramatically shortened life. But I don't think so. Why? Because the indications that the low-carbohydrate diet is the correct diet for humans comes from so many different sources. (And that's not even counting my years of hands-on care of many thousands of patients on such diets.)

If you look at the scientific literature, you find that the low-carbohydrate diet is, at worst, the equal of the low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet and at best triumphs over it in spectacular fashion. If you look at the anthropological evidence, the health of early humans took a turn for the worse when agriculture (read: high-carbohydrate diet) came along. Pasta, even whole-grain pasta, was the fast food of antiquity. If you look at the evolutionary evidence, it's pretty clear that the forces of natural selection molded us to function optimally on a higher-fat, higher-protein diet. And, finally, if you just look at the human physiology and biochemistry involved, it is clear that a diet high in carbohydrates is not good for us. Looking at all this graphically from one of my slides below, we can see that all the evidence vectors point to a low-carb diet as being the one most optimal for human health. Can a low-fat, high-carb diet make this claim? I don't think so. Though many misguided vegans try to make such a claim, their arguments are risible.

You can find a few studies that show a low-fat, high-carb diet performs OK, but where is the anthropological, evolutionary and biochemical data to confirm? When deciding what diet to follow, remember: you're betting you're life. Consequently, you should view the diet through the various lenses as laid out in the graphic above. If a new diet looks acceptable through one or two lenses, but not the others, just stick with your low-carb diet and be done with it.

Had Mr. Shragai performed the above analysis, he probably would not have followed the diet he did. As I wrote earlier, we have no idea as to what his outcome would have been had he gone on a low-carb diet instead of a low-fat one, but I can't help but believe it would have been better. Although Mr. Shragai's case is that of but one individual, since this vapid 1984 Time article came out launching the jihad against fat and cholesterol, the entire country became unwitting subjects in a long-term experiment testing the hypothesis that a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet is healthful. And in the intervening 26 years, obesity has skyrocketed and type II diabetes has reached epidemic proportions, leading me and many others to say that the low-fat diet has failed. At least as applied to large groups of subjects.

Let me sum up the take home message with an unrelated story that oddly illustrates the point. When I was taking flying lessons years ago, the tower once told me to cross one runway we were stopped short of and proceed to the next one. I goosed the engine and started across. My instructor pushed on the brakes and stopped us and asked me what I was doing. I said, "The tower told me to proceed to runway 15L." My instructor said, "Yes, but you didn't look for traffic coming in on runway 15R (the runway we had to cross) before proceeding. Here's what you've got to learn. If the pilot make a mistake, the pilot dies; if the control tower makes a mistake, the pilot dies. Always check for yourself."

Sobering words, but ones I remember. The same applies to diet. Don't let Time magazine or anyone else tell you what to do. It's your life. Don't bet it heedlessly.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter