Hazardous comets and asteroids are monitored by various space agencies under an umbrella effort known as Spaceguard. The vast majority of objects found so far are rocky asteroids. Yet UK-based astronomers Bill Napier at Cardiff University and David Asher at Armagh Observatory in Northern Ireland claim that many comets could be going undetected. "There is a case to be made that dark, dormant comets are a significant but largely unseen hazard," says Napier.

In previous work, Napier and Janaki Wickramasinghe, also at Cardiff, have suggested that when the solar system periodically passes through the galactic plane, it nudges comets in our direction (New Scientist, 19 April 2008, p 10).

These periodic comet showers appear to correlate with the dates of ancient impact craters found on Earth, which would suggest that most impactors in the past were comets, not asteroids.

Now Napier and Asher warn that some of these comets may still be zipping around the solar system. Other observations support their case. The rate that bright comets enter the solar system implies there should be around 3000 of them buzzing around, and yet only 25 are known.

We may not see them, say the pair, simply because they are too dark. (Astronomy & Geophysics, link).

Such dark comets are not unheard of. They occur when an "active" comet's reflective water ice has evaporated away, leaving behind an organic crust that only reflects a small fraction of light.

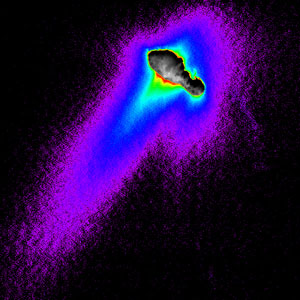

In 1983, Comet IRAS-Araki-Alcock passed by Earth at a distance of 5 million kilometres, the closest known pass by any known comet for 200 years. It was spotted only two weeks ahead of its closest approach. "It had only 1 per cent of its surface active," says Napier. Comet Borrelly, visited by NASA's Deep Space 1 probe in 2001, was found to have extremely dark patches over much of its surface.

"There may be merit to this idea," says Steve Larson of the University of Arizona's Catalina Sky Survey in Tucson, one of the main contributors to Spaceguard.

Clark Chapman at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, is sceptical, but points out that such dark comets "would absorb sunlight very well" and so could be detected by the heat they would emit.

Comment: For more on comets and very close calls, see here.