Scientists from the University of Alaska Fairbanks, Cornell University, University of Colorado Denver, University of Florida and Georgia Institute of Technology will conduct a variety of experiments at the UAF-operated research site.

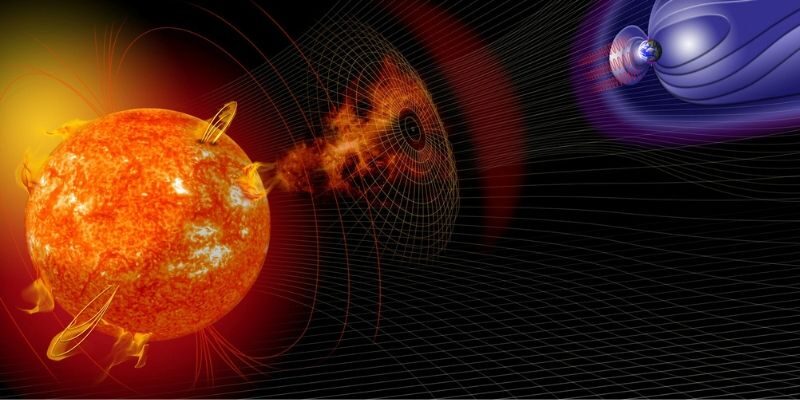

The experiments will focus on the ionosphere, the region of the atmosphere between about 30 and 350 miles above the Earth's surface.

Scientists will investigate ionosphere mechanisms that cause optical emissions. They'll also try to understand whether certain plasma waves — gas so hot that electrons get knocked off atoms — amplify other very low frequency waves. And they'll investigate how satellites can use plasma waves in the ionosphere for collision detection and avoidance.

Each day, the airglow could be visible up to 300 hundred miles from the HAARP facility in Gakona. The site lies about 200 miles northeast of Anchorage and 230 miles southeast of Fairbanks, or about 300 to 350 kilometers.

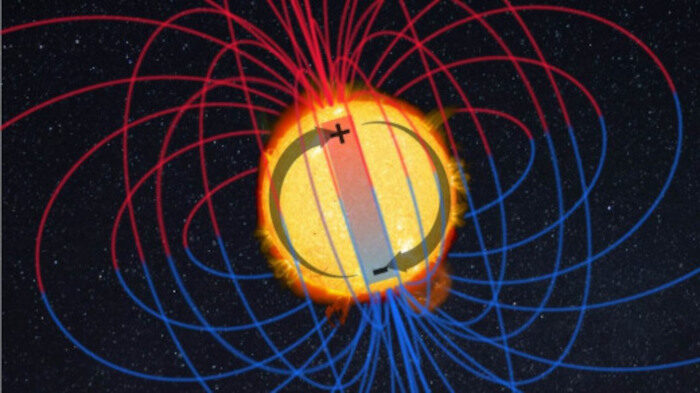

HAARP creates airglow by exciting electrons in Earth's ionosphere, similar to how solar energy creates natural aurora, with on and off pulses of high-frequency radio transmissions. HAARP's Ionospheric Research Instrument, a phased array of 180 high-frequency antennas spread across 33 acres, can radiate 3.6 megawatts into the upper atmosphere and ionosphere.

The airglow, if visible, will appear as a faint red or possibly green patch. Because of the way the human eye operates, the airglow might be easier to see when looking just to the side.

Comment: Very interesting timing for this experiment. See also:

HAARP and The Canary in the Mine

Mind Control and HAARP