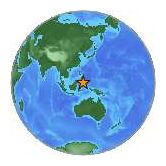

© USGSEarthquake Location

Thursday, February 10, 2011 at 14:41:57 UTC

Thursday, February 10, 2011 at 10:41:57 PM at epicenter

Time of Earthquake in other Time ZonesLocation

3.966°N, 123.125°E

Depth

512.2 km (318.3 miles)

Region

CELEBES SEA

Distances

330 km (205 miles) SW of General Santos, Mindanao, Philippines

330 km (205 miles) SE of Jolo, Sulu Archipelago, Philippines

1200 km (740 miles) SSE of MANILA, Philippines

2130 km (1320 miles) ENE of JAKARTA, Java, Indonesia