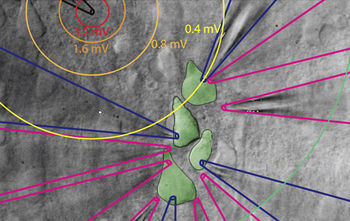

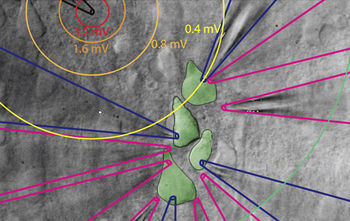

© Image from Figure 4 in Anastassiou et.,Nature Neuroscience, 2011Ephaptic coupling leads to coordinated spiking of nearby neurons, as measured using a 12-pipette electrophysiology setup developed in the laboratory of coauthor Henry Markram.

The brain - awake and sleeping - is awash in electrical activity, and not just from the individual pings of single neurons communicating with each other. In fact, the brain is enveloped in countless overlapping electric fields, generated by the neural circuits of scores of communicating neurons. The fields were once thought to be an "epiphenomenon, a 'bug' of sorts, occurring during neural communication," says neuroscientist Costas Anastassiou, a postdoctoral scholar in biology at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech).

New work by Anastassiou and his colleagues, however, suggests that the fields do much more - and that they may, in fact, represent an additional form of neural communication.

"In other words," says Anastassiou, the lead author of a paper about the work appearing in the journal

Nature Neuroscience, "while active neurons give rise to extracellular fields, the same fields feed back to the neurons and alter their behavior," even though the neurons are not physically connected - a phenomenon known as ephaptic coupling. "So far, neural communication has been thought to occur at localized machines, termed synapses. Our work suggests

an additional means of neural communication through the extracellular space independent of synapses."

Comment: The solution to the paradox? Pay attention to realty left and right, learning about the dangers of the world, but with periods of respite so that we are able to evaluate what we see and our decisions with a clear and fully functional mind. Reading SOTT.net is a great way to do the former, and as for the latter, Éiriú Eolas is an excellent practice for dealing with the negative effects of stress and anxiety.