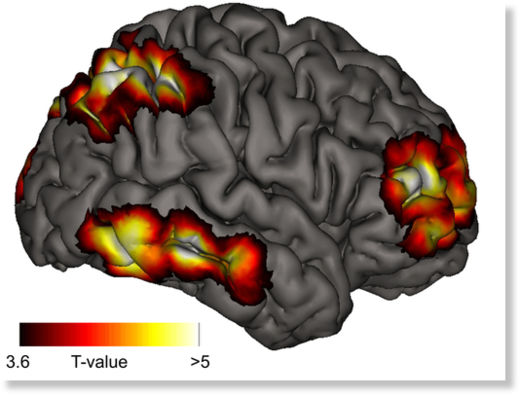

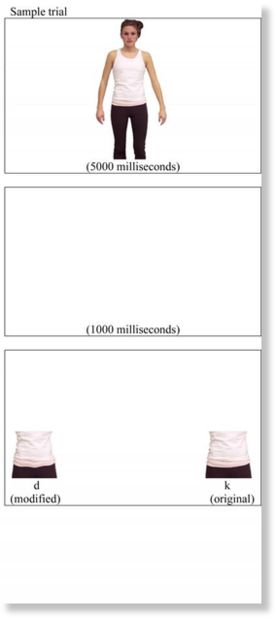

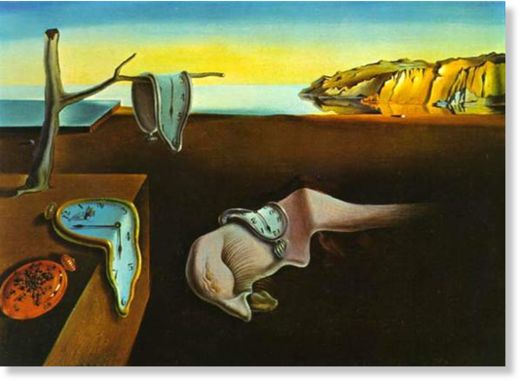

Which areas of the brain help us to perceive our world in a self-reflective manner is difficult to measure. During wakefulness, we are always conscious of ourselves. In sleep, however, we are not. But there are people, known as lucid dreamers, who can become aware of dreaming during sleep. Studies employing magnetic resonance tomography (MRT) have now been able to demonstrate that a specific cortical network consisting of the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, the frontopolar regions and the precuneus is activated when this lucid consciousness is attained. All of these regions are associated with self-reflective functions. This research into lucid dreaming gives the authors of the latest study insight into the neural basis of human consciousness.

The human capacity of self-perception, self-reflection and consciousness development are among the unsolved mysteries of neuroscience. Despite modern imaging techniques, it is still impossible to fully visualise what goes on in the brain when people move to consciousness from an unconscious state. The problem lies in the fact that it is difficult to watch our brain during this transitional change. Although this process is the same, every time a person awakens from sleep, the basic activity of our brain is usually greatly reduced during deep sleep. This makes it impossible to clearly delineate the specific brain activity underlying the regained self-perception and consciousness during the transition to wakefulness from the global changes in brain activity that takes place at the same time.

Comment: To learn more about the numerous mental, emotional and spiritual health benefits of meditation and breathing exercises visit the Éiriú Eolas Stress Control, Healing and Rejuvenation Program website, and try out the entire program here for free.

Read the following articles listed below for additional data on how meditation can help reduce chronic pain: