© CorbisResearch shows human instinct may be to help each other.

Without thinking, people act with more generosity than if they take some time to weigh the logic of their behavior.

Contrary to popular and pessimistic thought, the discovery suggests that, by default, our gut instincts lead us to be more helpful than selfish. That may explain why door-knocking and phone solicitations, which demand immediate responses, tend to bring in bigger donations than statistics-laden e-mail messages or direct mail, which puts people in a rational frame of mind and allows them to think for a while before deciding whether to give.

Likewise, people who commit heroic acts -- like the man who jumped onto New York City subway tracks in front of an oncoming train to save a young man having a seizure five years ago -- often make split-second decisions to do the altruistic thing.

"If you look at testimony of a lot of people like that describing their decisions, you can see they are heavily weighted towards intuitive thinking," said David Rand, a behavior scientist at Yale who conducted the new study while at Harvard. "People say, 'I didn't think about it. I just did it.'"

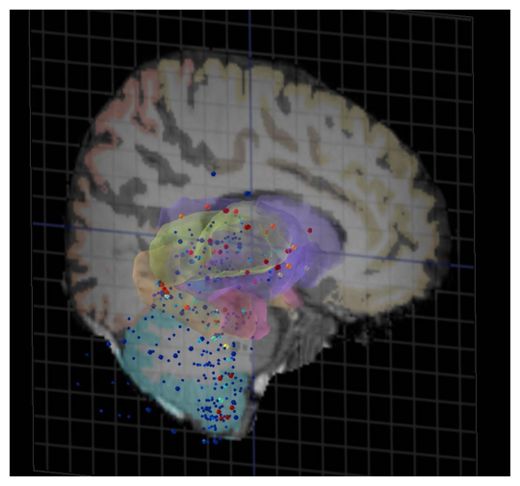

In a 2011 best-selling book called

Thinking, Fast and Slow, Nobel-Prize winning economist Daniel Kahneman argued that a lot of decision-making comes out of a tension between two types of brain processes. On the one hand, we have quick and intuitive thoughts, which are often emotional. The other mode is slower, allowing for more controlled and calculated thinking.

Until now, Rand said, researchers had yet to combine the two kinds of thought processes in a way that explained how people actually behaved.