The fact that our perception of the world appears to be so intransigent, however much we might reflect on it, tells us something unique about how our brains are wired. Compare the magician scenario with how we usually process information. Say you have five friends who tell you it's raining outside, and one weather website indicating that it isn't. You'd probably just consider the website to be wrong and write it off. But when it comes to conscious perception, there seems to be something strangely persistent about what we see, hear and feel. Even when a perceptual experience is clearly 'wrong', we can't just mute it.

Why is that so? Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) shed new light on this puzzle. In computer science, we know that neural networks for pattern-recognition - so-called deep learning models - can benefit from a process known as predictive coding. Instead of just taking in information passively, from the bottom up, networks can make top-down hypotheses about the world, to be tested against observations. They generally work better this way. When a neural network identifies a cat, for example, it first develops a model that allows it to predict or imagine what a cat looks like. It can then examine any incoming data that arrives to see whether or not it fits that expectation.

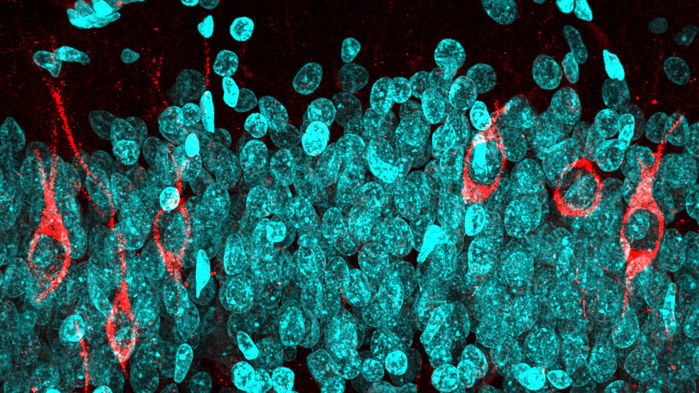

Comment: Kastrup has a response to critics of the above article here. In response to their claim that their results are "entirely irrelevant" to the metaphysics of the mind-body problem, Kastrup writes: Here's an image from one of the studies showing the patterns of decreased brain activity (blue) upon administering intravenous LSD: