© Adrian Niederhà | ShutterstockScientists now debate how much, rather than whether, biology contributes to sex differences in cognition.

London - A prevalent understanding, particularly in the 1980s, was that boys and girls are born cognitively the same. It was the way parents and society treated them that made them different.

Since then, a preponderance of research has called this belief into question. The majority of today's psychologists agree that some of the differences exhibited by

male and female brains are innate.

"We do socialize our boys and girls differently, but the contribution of biology is not zero," said Diane Halpern, a professor of psychology at Claremont McKenna College in California, who has been studying

cognitive gender differences for 25 years. Halpern was a keynote speaker at the British Psychological Society Annual Conference here last Thursday (April 19).

How much, rather than whether, biology contributes is where the unusually heated debate is now focused, she said.

Differences confirmed (so far)Some of the many gender differences that float in popular consciousness have more support than others.

The ones that have been consistently found across cultures, life spans and even

across species are the most likely - but by no means guaranteed - to have some biological underpinning.

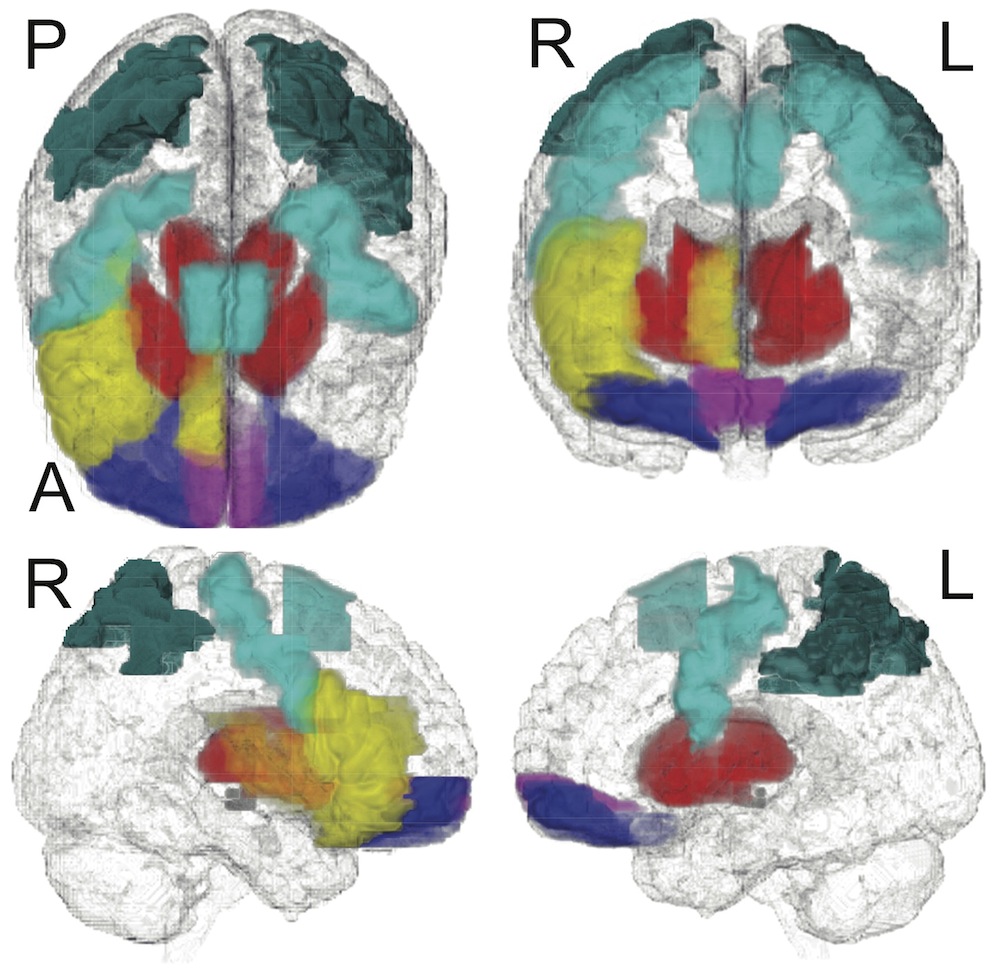

Across age groups, species and nations, males tend to be better at various spatial skills. For example, male dominance in rotating an object in their minds, a quite large difference that has been reliably found for the last 35 years, has recently been documented in infants as young as 3 months old. Similarly, on average, males across cultures and species are better at judging angle orientation and navigating by cardinal direction.

Females, on the other hand, tend to have more verbal fluency and greater memory for objects - that is, "they are better at remembering where things are," Halpern said during her talk. Women and females from other species are more likely to navigate by using landmarks than cardinal direction.

"But you can get there using both," Halpern told LiveScience, pointing out that having different skills does not mean that men and women have different levels of intelligence. "There is not a smarter sex," she said.

In general, across a variety of tests, differences seem to fall particularly at the tails of distribution curves, with more males doing very poorly

and more males doing exceedingly well.

Comment: It's been found that writing excercises can help with changing the way one thinks of themselves. For more information, see this Sott article:

Writing to Heal