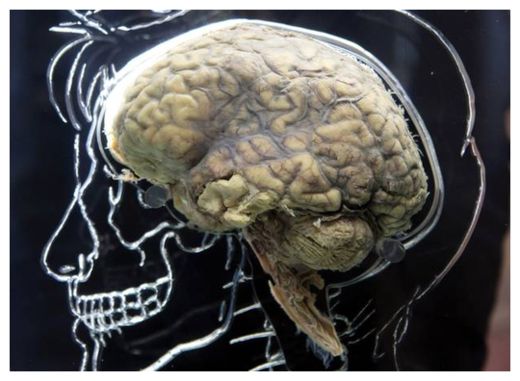

The researchers had conducted brain scans of university students for a study before the Great East Japan Earthquake struck in 2011. After the earthquake, they repeated the scans on 37 of the same people, and tracked stress-induced changes in their brains in the following months.

"Most importantly, what these findings show, is that the brain is dynamic - that it's responding to things that are going on in our environment, or things that are part of our personality," said Rajita Sinha, professor of psychiatry at Yale School of Medicine, who wasn't involved in the study.

In the brain scans taken immediately after the incident, the researchers found a decrease in the volume of two brain regions, the hippocampus and orbitofrontal cortex, compared with the scans taken before the incident.

One year later, the researchers repeated the scans and found that the hippocampus continued to shrink, and people's levels of depression and anxiety had not improved.

However, other changes in the brain had reversed, the researchers found: The volume of the orbitofrontal cortex had increased. Moreover, this increase was correlated with survivors' self-esteem scores soon after the earthquake, according to the study published today (April 29) in the journal Molecular Psychiatry.