© Alexey Fursov | ShutterstockHow often do you pray? Or do you think it's a waste of time?

This December is chock full of "holy days," or holidays. On Dec. 25, Christians commemorate Christmas. For Jews, Hanukkah starts this year on Dec. 20 in the Western and international Gregorian calendar. Shia Muslims, meanwhile, celebrate Ashura today (Dec. 4), the 10th day of the Islamic lunar calendar's first month. Yet others in the Northern Hemisphere will party on Dec. 22 for the winter solstice, as druids might have ritualistically done so at Stonehenge in the U.K. 4,000 years ago.

Religion, it goes without further saying, is a very popular phenomenon. In the U.S., as in much of the world, a majority of people claim to practice some form of it. According to recent surveys, around 80 percent of American adults say

they belong to an organized religion.A minority of that population takes its religion very seriously. These individuals' behaviors and attitudes are largely influenced by what is perceived to conform to their faiths' dogmas. On the opposite end, another, smaller percentage of the population thinks that

religion is absolute hooey. Psychologists, sociologists and neurologists continue to study why some gobble up religion as profound truth while others reject it as superstition.

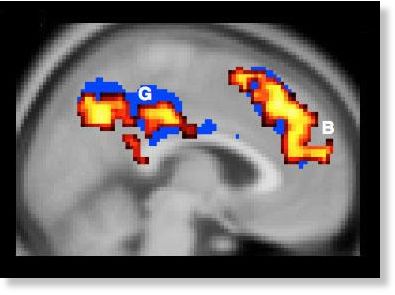

"This whole area [of research] teaches us something about

the human mind and brain," said Andrew Newberg, director of research at the Myrna Brind Center of Integrative Medicine at Thomas Jefferson University and author of

How God Changes Your Brain (Ballantine Books, 2009).

"There are a lot of philosophical and theological implications of this work and about how we understand the world," Newberg added.