"Having active control over a learning situation is very powerful and we're beginning to understand why," said University of Illinois psychology and Beckman Institute professor Neal Cohen, who led the study with postdoctoral researcher Joel Voss. "Whole swaths of the brain not only turn on, but also get functionally connected when you're actively exploring the world."

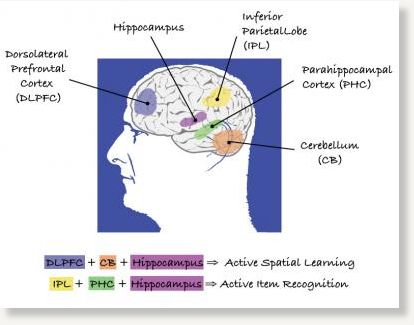

The study focused on activity in several brain regions, including the hippocampus, located in the brain's medial temporal lobes, near the ears. Researchers have known for decades that the hippocampus is vital to memory, in part because those who lose hippocampal function as a result of illness or injury also lose their ability to fully form and retain new memories.

But the hippocampus doesn't act alone. Robust neural connections tie it to other important brain structures, and traffic on these data highways flows in both directions. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies, which track blood flow in the brain, show that the hippocampus is functionally connected to several brain networks - distinct regions of the brain that work in tandem to accomplish critical tasks.