People who don't care - or don't need to care - what others think of them show how crucial reputation is to civilization. Understanding it could reduce crime, improve ethical behavior and rein in Wall Street excesses

About one in every 100 people doesn't care what others think of him. These people are hard to spot. They are usually physically healthy, and their intelligence is often above average. Yet, in the words of one psychiatrist, they lie without compunction, cheat, steal, and casually violate any and all norms of social conduct whenever it suits their whim. They have no concern for others' suffering, no remorse when caught, and punishment does little to change them. They are called psychopaths.

Mental-health professionals have usually treated psychopathic behavior as a disorder - a large proportion of the prison population, after all, has been diagnosed with some version of the trait. But viewed from an evolutionary angle, psychopathy looks more like a feature than a bug. Most people are cooperative, trusting and generous. This pays off in the long term. It also creates an opening for those who would rather prey on society than join it.

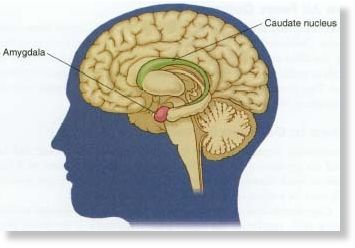

A psychopath's deceitful, manipulative, and callous nature equips him (it's several times more likely to be a "him") to fill this niche. Psychopaths' deficit is in empathy, not reason. They understand morality, but they are immune to other people's emotions. There aren't many openings for psychopaths, because if there were lots of them, there would be no society to plunder. Evolutionary biologists call this frequency dependence: it means that the rarer a trait becomes, the more it pays off. This advantage when rare makes the trait more common, which reduces its advantage. The effect is to keep multiple traits in balance. Sex is one example of frequency dependence: if males were more common than females, they would be less likely to find a mate, so it would pay to have female offspring, pushing the sex ratio back toward equality. Similarly, mathematical models suggest that if antisocial behavior is rare enough, it can prosper.