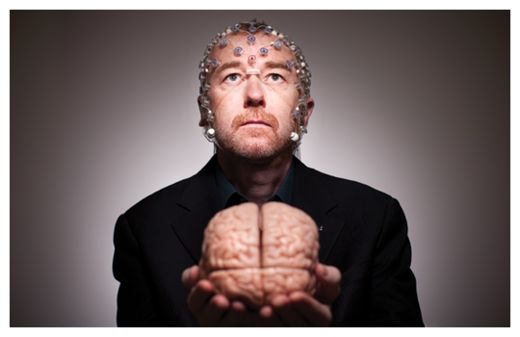

© John Hryniuk

Adrian Owen still gets animated when he talks about patient 23. The patient was only 24 years old when his life was devastated by a car accident. Alive but unresponsive, he had been languishing in what neurologists refer to as a vegetative state for five years, when Owen, a neuro-scientist then at the University of Cambridge, UK, and his colleagues at the University of Liège in Belgium, put him into a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) machine and started asking him questions.

Incredibly, he provided answers. A change in blood flow to certain parts of the man's injured brain convinced Owen that patient 23 was conscious and able to communicate. It was the first time that anyone had exchanged information with someone in a vegetative state.

Patients in these states have emerged from a coma and seem awake. Some parts of their brains function, and they may be able to grind their teeth, grimace or make random eye movements. They also have sleep - wake cycles. But they show no awareness of their surroundings, and doctors have assumed that the parts of the brain needed for cognition, perception, memory and intention are fundamentally damaged. They are usually written off as lost.

Owen's discovery

1, reported in 2010, caused a media furore. Medical ethicist Joseph Fins and neurologist Nicholas Schiff, both at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York, called it a "potential game changer for clinical practice"

2. The University of Western Ontario in London, Canada, soon lured Owen away from Cambridge with Can$20 million (US$19.5 million) in funding to make the techniques more reliable, cheaper, more accurate and more portable - all of which Owen considers essential if he is to help some of the hundreds of thousands of people worldwide in vegetative states. "It's hard to open up a channel of communication with a patient and then not be able to follow up immediately with a tool for them and their families to be able to do this routinely," he says.

Many researchers disagree with Owen's contention that these individuals are conscious. But Owen takes a practical approach to applying the technology, hoping that it will identify patients who might respond to rehabilitation, direct the dosing of analgesics and even explore some patients' feelings and desires. "Eventually we will be able to provide something that will be beneficial to patients and their families," he says.

Still, he shies away from asking patients the toughest question of all - whether they wish life support to be ended - saying that it is too early to think about such applications. "The consequences of asking are very complicated, and we need to be absolutely sure that we know what to do with the answers before we go down this road," he warns.

Comment: For more information about an easy to use approach to Meditation check out the Eiriu Eolas Stress Control, Healing and Rejuvenation Program here.