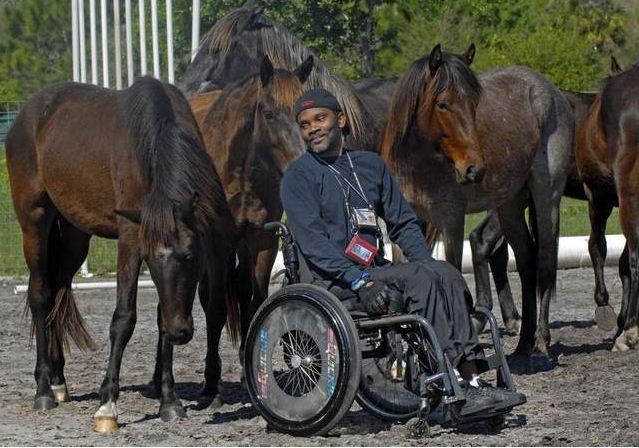

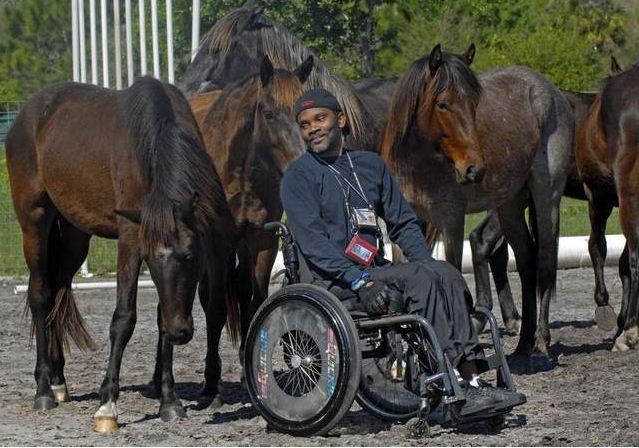

© Rik Jesse / Florida TodayCurtis Arnett participates in equine-assisted psychotherapy at Forever Florida near St. Cloud. He was able to build trust and establish boundaries with one particular horse. The West Melbourne man was rendered a paraplegic in 2005 after a motorcycle accident.

Chris Hamrick still is haunted by the memories.

It was Feb. 27, 1991, during the first Gulf War. His platoon leader stepped on a land mine, injuring the sergeant, killing his best friend and blowing off part of Hamrick's left leg.

"It don't ever go away," said the 44-year-old Palm Bay resident, who sees a therapist once, sometimes twice a week, for post-traumatic stress disorder. "You learn how to cope better. It helps just to be able to vent."

Recently, instead of sitting in an office and talking about his feelings, he tried something different -- a therapy involving a three-legged horse named La Nina , who lost one of her hind legs when it got wrapped in a wire fence several years ago. The session was at the Equine Education Center at Forever Florida near St. Cloud.

"The three-legged horse intrigued me," Hamrick said. "That's a pretty heavy animal to try to get around on three legs and develop a gallop. It takes a will to survive. I went through quite a bit myself, complications off and on, being an amputee. You got to decide that you are willing to accept the struggle and keep on going. It's interesting to see how an animal deals with it."

A growing number of mental health counselors are incorporating horses into their sessions, using the animals to treat a host of mental health issues ranging from eating disorders to substance abuse to post-traumatic stress disorder. NARHA, formerly known as the North American Riding for the Handicapped Association, has been offering equine-facilitated psychotherapy and learning since 1995 and calls them fast-growing disciplines in the equine industry.

Comment: There is one proven technique

Visit the Éiriú Eolas site or participate on the forum to learn more about the scientific background of this program and then try it out for yourselves, free of charge.