But the records are silent on one important point. Exactly where did the massacre occur on the moonlit night of March 19, 1863?

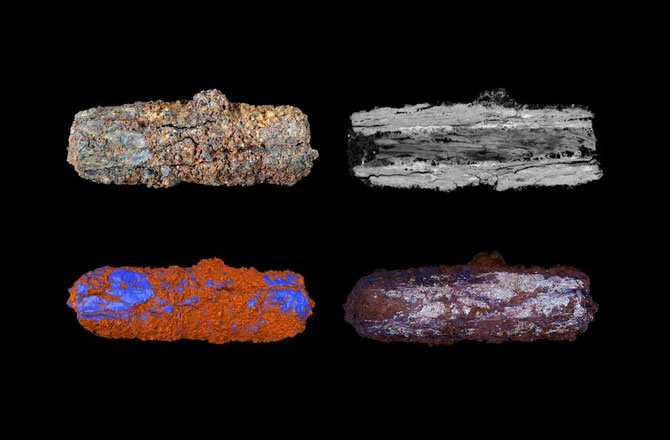

An archaeological find in what is today a vast alkali playa has revealed a cache of bullets, musket balls, cavalry uniform buttons and Native American artifacts that Paiute tribal members and researchers believe are evidence of the grim chapter in Owens Valley history.

The site has been lost to history for more than 100 years, a time in which Los Angeles drained most of Owens Lake to slake the growing city's thirst. Strong winds and torrential rain in 2009 may have uncovered the artifacts, which were found by Los Angeles Department of Water and Power archaeologists surveying the area in preparation for dust mitigation projects.

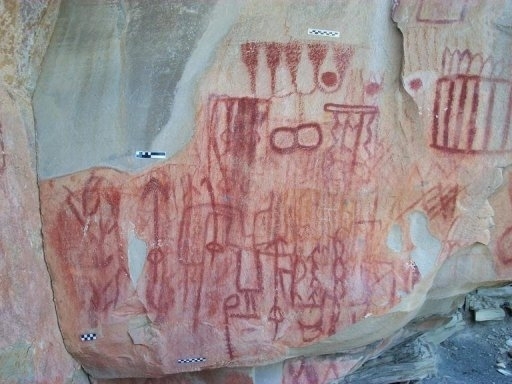

Dust wasn't a problem in the mid-19th century at Owens Lake, 200 miles north of Los Angeles. Native Paiutes hunted along the lake and diverted the flow of local streams to irrigate fields of wild hyacinth and yellow nutgrass.

But disputes arose as settlers poured into the valley and began ranching on the tribe's pasturelands. U.S. troops were sent to protect the settlers and the land and water they had effectively stolen from the Paiutes.