© Unknown

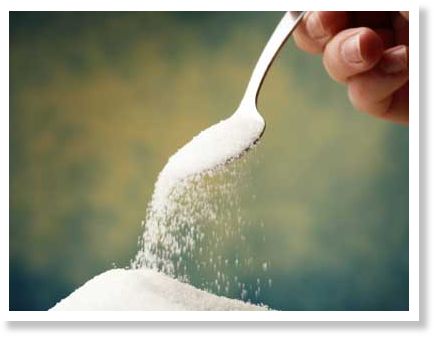

Americans think an awful lot about sucrose -- table sugar -- but only in certain ways. We crave it and dream up novel ways to combine it with other ingredients to produce delectable foods; and we worry that we eat too much of it and that it is making us unhealthy or fat. But how often do Americans think about where sugar actually comes from or the people who produce it? As a tropical crop, sugarcane cannot grow in most U.S. states. Most of us do not smell the foul odors coming from sugar refineries, look out over vast expanses of nothing but sugarcane, or speak to those who perform the hard labor required to grow and harvest sugarcane.

Of course, sugar can be made from beets, a temperate crop, and more than half of sugar produced in the United States is. But globally, most of the story of sugar, past and present, centers around sugarcane, not beets, and as biofuels become more common, it is sugarcane that is cultivated for ethanol. What's more, some conscious eaters avoid beet sugar as most of it is now made from genetically modified sugar beets.

While I do not fool myself that sugar is "healthy," if I am going to satisfy my sweet tooth, I prefer cane sugar, maple syrup, agave nectar, or honey over the other choices: beet sugar, high fructose corn syrup, and artificial sweeteners. Of the bunch, most Americans can find only honey and perhaps maple syrup sustainably and locally produced, but cane sugar is often the most versatile product for baking.

As a major consumer of cane sugar, I was disturbed to learn the realities of cane sugar production when I visited a sugarcane-producing area in Bolivia.