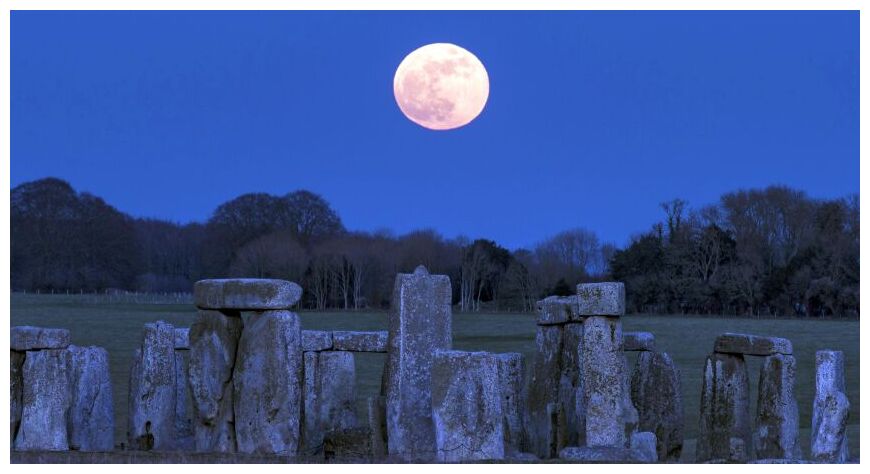

© Public DomainOak Island.

Oak Island, located in Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia, is a small 140-acre island which has been the

subject of an ongoing treasure hunt since 1795.The earliest human occupation of the region dates back several thousand years to the ancestors of the Mi'kmaq, an indigenous First Nations people of Canada's Atlantic Provinces.

Europeans established permanent settlements in the area during the mid-18th century through the Shorham grant, an edict which offered free land grants to attract settlers and generate population growth.

At the time, Oak Island was known locally as "Smith's Island" (named for Edward Smith, an early settler), but was renamed to "Gloucester Isle" in 1778, and shortly after to "Oak Island" supposedly because of the red oaks growing on the island.

The following account is neither exact nor complete, but is a rough summary of the reports and materials published in sequence.

The history of the Oak Island treasure hunt begun in 1795, when a young Daniel McInnes discovered evidence of tree felling on the island's interior and a clearing with a shallow saucer-shaped depression.

McInnes likely envisioned stumbling across a pirate cache, as the Novia Scotia region was known to be a hide-out for pirates in the 17th and 18th centuries during the Golden Age of Piracy.

The most infamous pirate to be associated with the Oak Island legend is Captain Kidd, however, there is little supporting evidence other than hearsay, and any association is merely speculative.

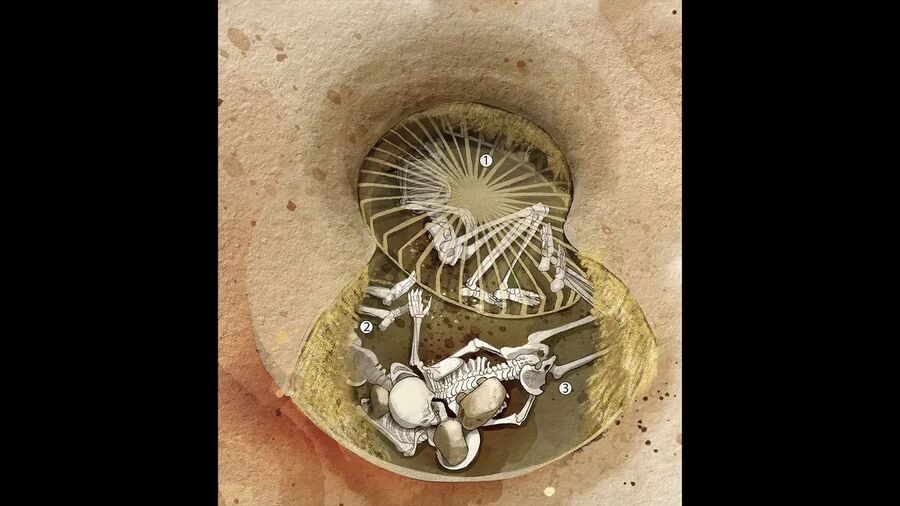

McInnes returned to the island with John (Jack) Smith and Anthony Vaughan, and begun excavating the depression until they discovered a layer of flagstones sourced from the Gold River several miles to the north.

Upon removing the flagstones, it is claimed that the trio found a shaft made by human hands (evidenced by pick marks in the hard clay walls), and continued to excavate the shaft interior to reveal several platforms of wooden logs at a depth of every 10 feet.

This shaft would later become known as the "Money Pit".

Comment: See also: