In research published in the journal PLOS ONE, archaeologists describe the discovery, at the Neolithic (Late Stone Age) lakeshore village of La Marmotta, about 30 km northwest of central Rome.

The quality and complexity of these prehistoric vessels suggest that several significant advances in sailing occurred during the late Stone Age, paving the way for the spread of the ancient world's most important civilizations.

The authors note that the spread of Neolithic culture through Europe was chiefly carried out along the shores of the Mediterranean.

"Many of the most important civilisations in Europe originated on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea," they write. "Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans and Carthaginians plied that practically enclosed sea to move rapidly along its coasts and between its islands."

The writers say Neolithic communities occupied the whole Mediterranean between 9,500 and 9,000 years ago. They reached the Atlantic coast of Portugal by about 5400 BCE.

"It is clear that the Mediterranean Sea must have often been used for travel, as boats allowed rapid movements of population, contacts and exchange of goods," the authors say.

It's well known that maritime trade links existed in the Mediterranean during the Neolithic, although until now it was unclear how adept these early mariners were at handling the waves.

Navigating through this uncertainty, the authors of a new study have analyzed five dug-out canoes that were discovered at a 7,000-year-old settlement that now lies at the bottom of an Italian lake.

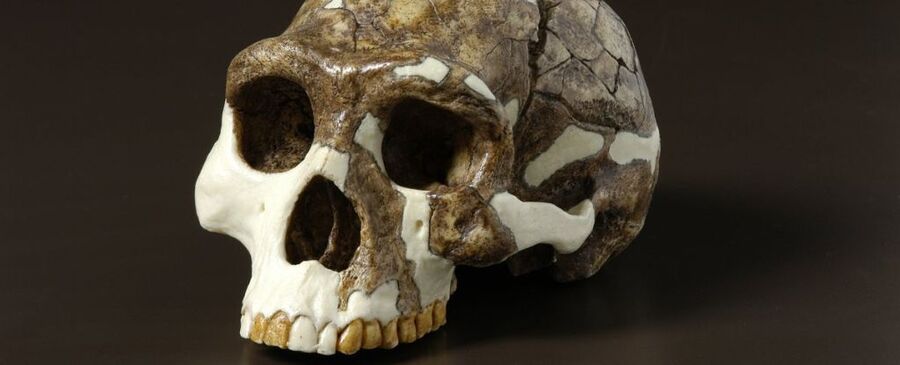

Comment: It's notable that evidence of cranial deformation, as well as natural, unusually shaped, skulls - that, one would assume, are what people were were attempting to imitate - have been found in sites that date as far back as 10,000 years ago, and across much of the planet: