OF THE

TIMES

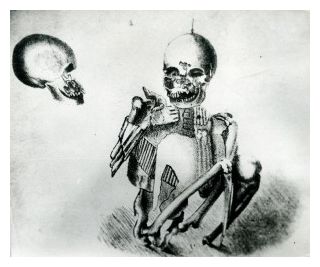

"...a belt composed of brass tubes, each four and a half inches in length and three-sixteenths of an inch in diameter... the length of the tube being the width of the belt. The tubes are of thin brass, cast upon hollow reeds, and were fastened together by pieces of sinew... The arrows are of brass, thin, flat, and triangular in shape, with a round hole cut through near the base. The shaft was fastened to the head by inserting the latter in an opening at the end of the wood, and then tying it with a sinew through the round hole, a mode of constructing the weapon never practiced by the Indians..."There is some historical debate as to the last statement. Brass was not unfamiliar to native tribes who had been known to trade goods for brass kettles which they melted down for arrowheads and adornments in the 1600s. One brass tube was donated to Copenhagen's Peabody Museum in 1887; analysis revealed it was indeed brass. Without modern dating techniques, though, the age of the skeleton couldn't be determined. Some people insisted it was some lost Indian chief. Others suggested it was undoubtedly Phoenician and proved that some forgotten Mediterranean peoples had crossed the Atlantic and formed the mythical Atlantis "beyond the Pillars of Hercules" (or Rock of Gibraltar) as recorded by Plato. Others insisted it was just a hoax.