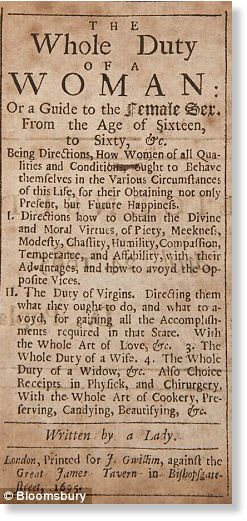

© Pierre-Jean Texier, National Center of Scientific Research, FranceEarly humans were using stone hand axes as far back as 1.8 million years ago.

A new study suggests that

Homo erectus, a precursor to modern humans, was using advanced toolmaking methods in East Africa 1.8 million years ago, at least 300,000 years earlier than previously thought. The study, recently published in

Nature, raises new questions about where these tall and slender early humans originated and how they developed sophisticated tool-making technology.

Homo erectus appeared about 2 million years ago, and ranged across Asia and Africa before hitting a possible evolutionary dead-end, about 70,000 years ago. Some researchers think

Homo erectus evolved in East Africa, where many of the oldest fossils have been found, but the discovery in the 1990s of equally old

Homo erectus fossils in the country of Georgia has led others to suggest an Asian origin. The study in Nature does not resolve the debate but adds new complexity. At 1.8 million years ago,

Homo erectus in Dmanisi, Georgia was still using simple chopping tools while in West Turkana, Kenya, according to the study, the population had developed hand axes, picks and other innovative tools that anthropologists call "Acheulian."

"The Acheulian tools represent a great technological leap," said study co-author Dennis Kent, a geologist with joint appointments at Rutgers University and Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. "Why didn't

Homo erectus take these tools with them to Asia?"