View Gallery

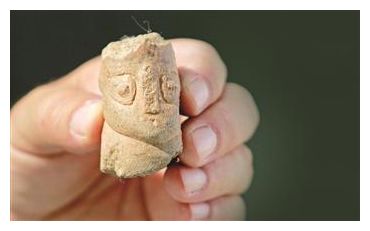

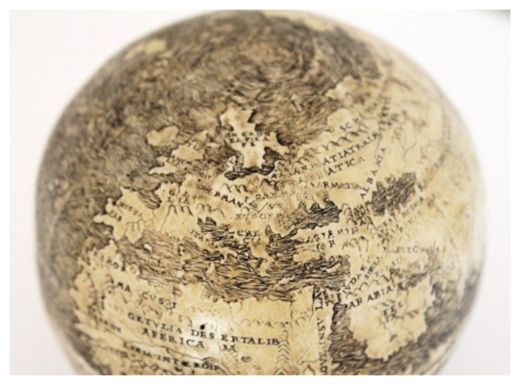

The globe, about the size of a grapefruit, is labeled in Latin and includes what were considered exotic territories such as Japan, Brazil and Arabia. North America is depicted as a group of scattered islands. The globe's lone sentence, above the coast of Southeast Asia, is "Hic Sunt Dracones."

" 'Here be dragons,' a very interesting sentence," said Thomas Sander, editor of the Portolan, the journal of the Washington Map Society. The journal published a comprehensive analysis of the globe Monday by collector Stefaan Missinne. "In early maps, you would see images of sea monsters; it was a way to say there's bad stuff out there."

The only other map or globe on which this specific phrase appears is what can arguably be called the egg's twin: the copper Hunt-Lenox Globe, dated around 1510 and housed by the Rare Book Division of the New York Public Library. Before the egg, the copper globe had been the oldest one known to show the New World. The two contain remarkable similarities.

After comparing the two globes, Missinne concluded that the Hunt-Lenox Globe is a cast of the engraved ostrich egg. Many minute details, such as the lines and contours of the egg's territories, oceans and script, match those on the well-studied Hunt-Lenox Globe.

The egg's shape is slightly irregular, while the copper globe is a perfect sphere. Also, the markings around the equator of the egg, where the two halves are joined, appear quite muddled.