Neighborhoods, farms, and roads are 1000 years older than previous discoveries.

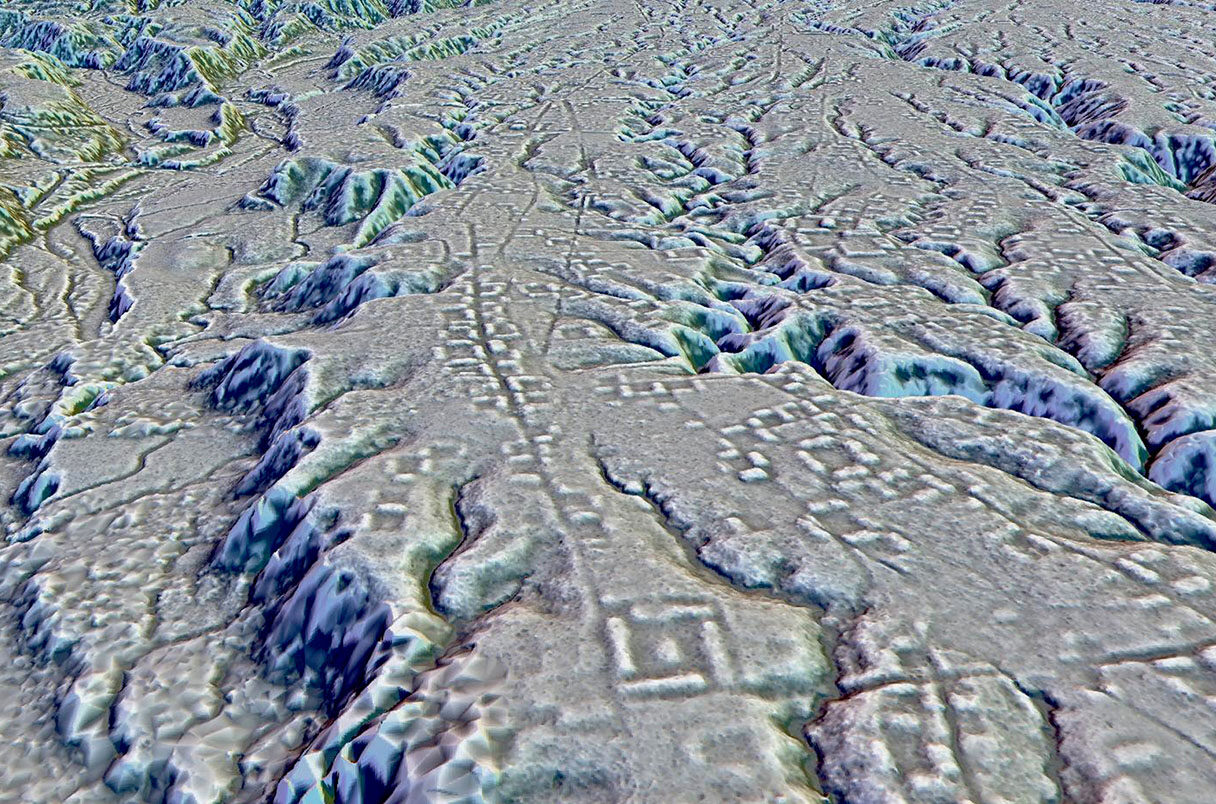

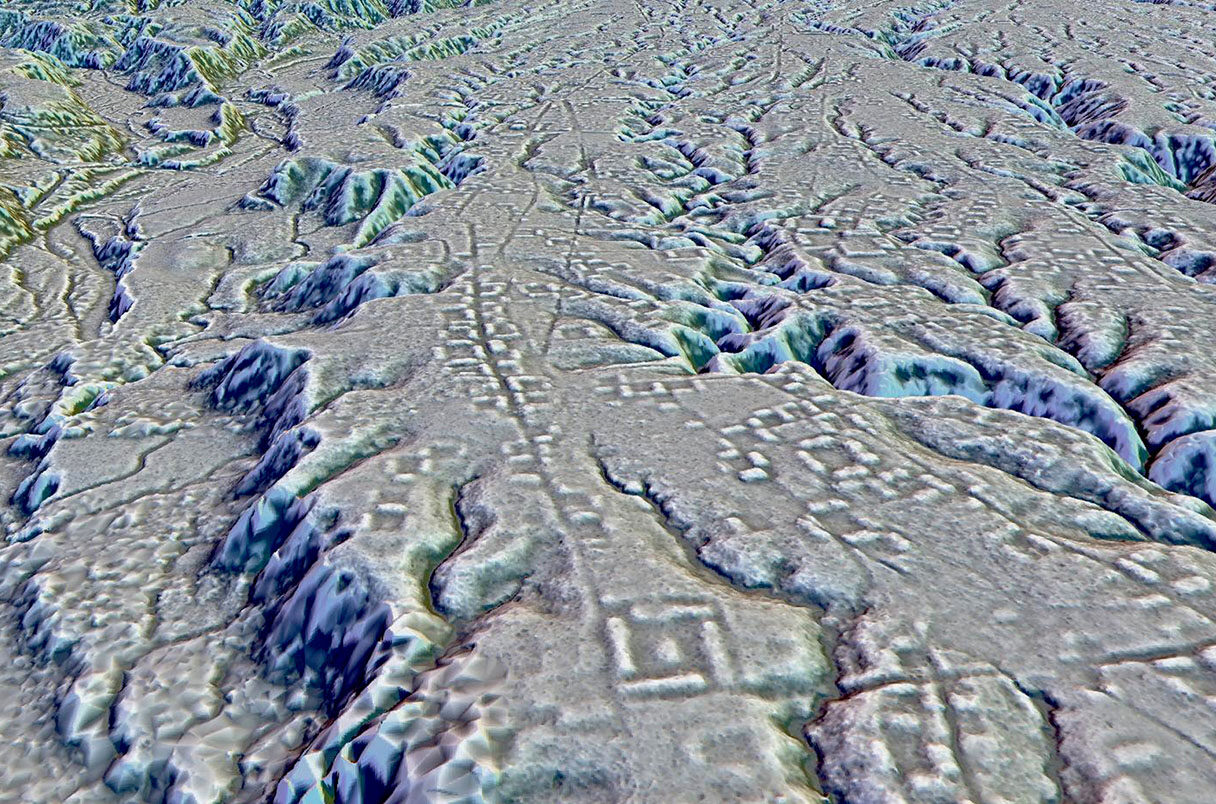

© ANTOINE DORISON AND STÉPHEN ROSTAINA lidar map of the city of Kunguints in the Ecuadorian Amazon reveals ancient streets lined with houses.

Archaeologists once believed the ancient Amazon rainforest was an inhospitable place, sparsely populated by bands of hunter-gatherers. But the remains of enormous

earthworks, pyramids, and roads from Bolivia to Brazil discovered over the

past 2 decades have proved conclusively that the Amazon was home to large, complex societies long before European colonizers arrived. Now, there's evidence that another human society — the oldest yet — left its mark on the region:

A dense network of interconnected cities, now hidden beneath the forest in Ecuador's Upano Valley, has been revealed by the laser mapping technology called lidar. The settlements,

described today in Science, are at least 2500 years old, more than 1000 years older than any other known complex Amazonian society.

Lidar, which allows researchers to see through forest cover and reconstruct the ancient sites below, "is revolutionizing our understanding of the Amazon in pre-Columbian times," says Carla Jaimes Betancourt, an archaeologist at the University of Bonn who wasn't involved in the new work. Finding such an ancient urban network in the Upano Valley highlights the long-unrecognized diversity of ancient Amazonian cultures, which archaeologists are just beginning to be able to reconstruct.

Stéphen Rostain, an archaeologist at CNRS, France's national research agency, began excavating in the Upano Valley nearly 30 years ago. His team focused on two large settlements, called Sangay and Kilamope, and found mounds organized around central plazas, pottery decorated with paint and incised lines, and large jugs holding the remains of the traditional maize beer

chicha. Radiocarbon dates showed the Upano sites were occupied from around 500 B.C.E. to between 300 C.E. and 600 C.E. "I knew that we had a lot of mounds, a lot of structures," Rostain says. "But I didn't have a complete overview of the region."

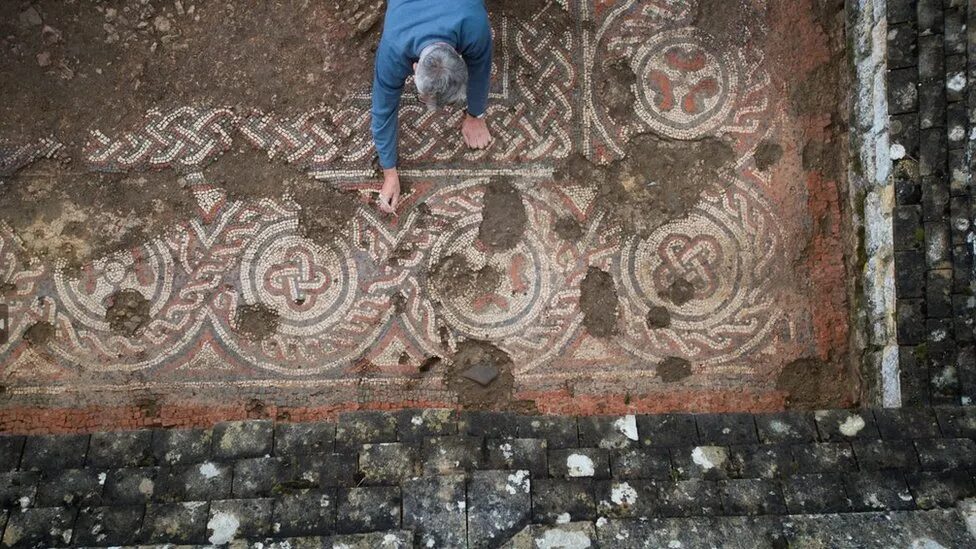

Comment: This follows another recent, related discovery: Mysterious early medieval cemetery unearthed in Wales reveals trade networks reaching as far as North Africa