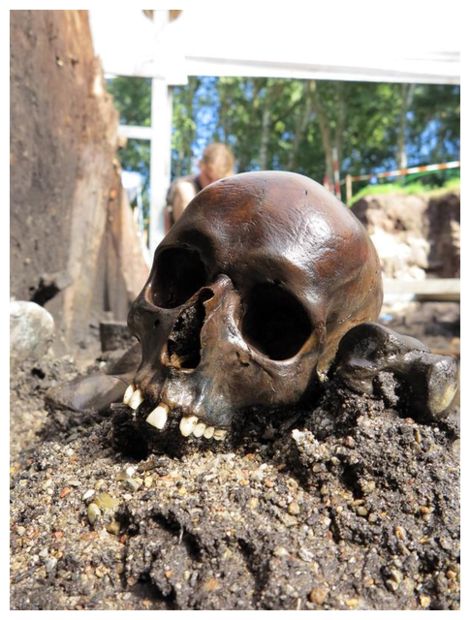

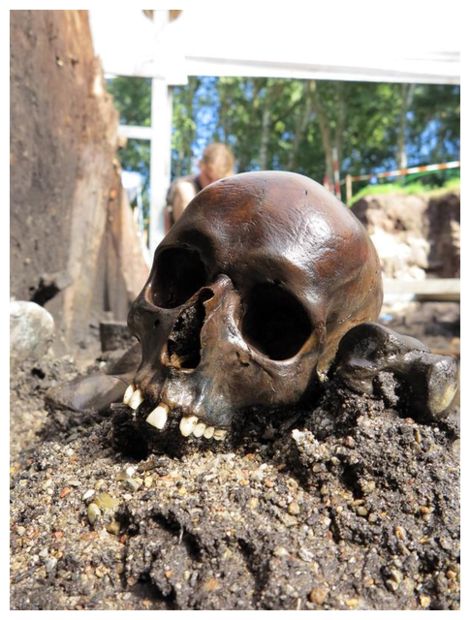

© Ejvind Hertz/Skanderborg MuseumAmong the remains found at an archeological site in what is now Aiken, Denmark is a skull from early Roman Empire times.

In the days of ancient Rome, it was never a good idea to send amateurs to pacify the Germanic tribes. The Emperor Augustus found this out in A.D. 9, when his handpicked crony, Varus, blundered into a series of ambushes in the Teutoburg Forest and lost about 20,000 men in three days.

Several years later, another Roman army stopped at that battlefield, a bit south of the modern German city of Bremen, to clean up the scene. According to the historian Tacitus, they found "bleaching bones, scattered or in little heaps," while "hard by lay splintered spears and limbs of horses." Human skulls "were nailed prominently on the tree-trunks." There were "gibbets and torture pits for the prisoners," and "in the neighboring groves stood the savage altars at which they [the Germanic tribes] had slaughtered the tribunes and chief centurions." Varus had fallen on his sword after the battle, either out of shame or because he was terrified. It was impossible to know which.

Scattered archaeological evidence has long suggested that the warriors of ancient Germania were not kind-hearted in victory. But new evidence suggests just how grisly things were at about the time of Christ, when an aggressive and well-organized young Roman empire was trying - ultimately, unsuccessfully - to subdue the equally aggressive inhabitants of Germania.

A Danish team, working in a bog about 325 miles south of the site of the Roman massacre, is analyzing the recently excavated remains of 40 men, part of a larger contingent of as many as 200 soldiers, whose bodies were apparently hacked to bits and thrown into the shallows of Lake Mosso after a battle that took place between German rivals, probably a few years before the Varus massacre. The Alken bog, lying today beneath a lakeside meadow, conceals the largest concentration of apparent war dead ever found from that era. These findings, added to artifacts from other sites and the writings of the ancient Romans, are supplying insights into a warlord culture of fiercely egalitarian German tribes that fought constantly, routinely slaughtered their enemies and offered their bodies - and their weapons - to their gods.