The ancient embalmers also didn't always leave the mummy's heart in place, the researchers added.

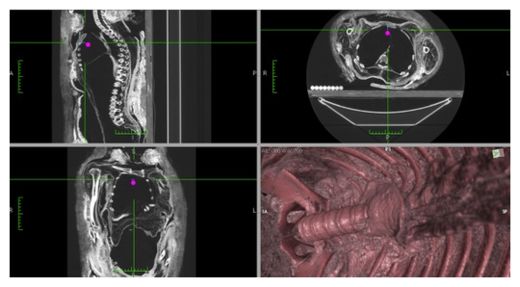

The findings, published in the February issue of HOMO - Journal of Comparative Human Biology, come from analyzing 150 mummies from the ancient world.

Mummy history

In the fifth century B.C., Herodotus, the "father of history," got an inside peek at the Egyptian mummification process. Embalming was a competitive business, and the tricks of the trade were closely guarded secrets, said study co-author Andrew Wade, an anthropologist at the University of Western Ontario.

Herodotus described multiple levels of embalming: The elites, he said, got a slit through the belly, through which organs were removed. For the lower class, mummies had organs eaten away with an enema of cedar oil, which was thought to be similar to turpentine, Herodotus reported. [See Images of Egyptian Mummification Process]

In addition, Herodotus claimed the brain was removed during embalming and other accounts suggested the heart was always left in place.

"A lot of his accounts sound more like tourist stories, so we're reticent to take everything he said at face value," Wade told LiveScience.