© Alberto TapiaFar-flung cousin? This 8000-year-old skeleton of a hunter-gatherer, found in a Spanish cave, is genetically similar to skeletons found in central and Eastern Europe.

Until about 8500 years ago, Europe was populated by nomadic hunter-gatherers who hunted, fished, and ate wild plants. Then, the farming way of life swept into the continent from its origins in the Near East, including modern-day Turkey. Within 3000 years most of the hunter-gatherers had disappeared. Little is known about these early Europeans. But a new genetic analysis of two 8000-year-old skeletons from Spain suggests that they might have been a remarkably cohesive population both genetically and culturally - a conclusion that other researchers find intriguing but possibly premature.

The

first modern human hunter-gatherers occupied Europe at least 40,000 years ago. But their fortunes waxed and waned with fluctuations in climate, and during the height of the last ice age - between about 25,000 and 20,000 years ago - they were forced to take refuge in southern European regions such as modern-day Spain, Portugal, and southern France. Only after 12,000 years ago, when a permanent warming trend set in, were they able to spread across all of Europe again, marking the beginning of a period called the Mesolithic.

Yet, while researchers have intensively studied the ancient farmers who followed them, relatively little is known about Europe's Mesolithic people. Scientists have extracted

ancient DNA from dozens of farmer skeletons, but from fewer than 30 Mesolithic skeletons. Nearly all of these are from central and Eastern Europe.

In the new study, published online today in

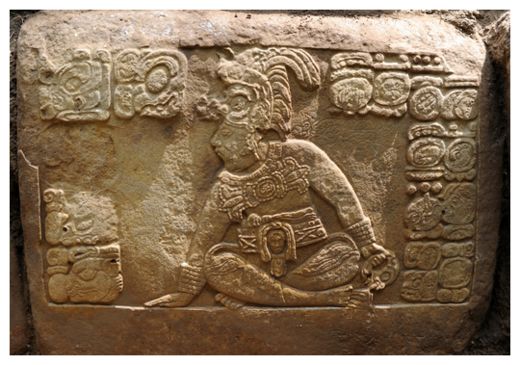

Current Biology, a team led by geneticist Carles Lalueza-Fox of the University of Barcelona in Spain sequenced DNA from both mitochondria, the cell's tiny energy plants, and the cell nucleus from two complete, remarkably well-preserved skeletons found in 2006 in a cave complex called La Braña-Arintero in northwest Spain. The remains, both males (as determined from the size of their pelvises and their DNA), were a few meters apart and found in a crouching position. Radiocarbon dates pegged both skeletons at about 8000 years old

*; the dates were so close in fact, within the margin of error of the technique, that the humans may have been deposited in the cave at the same time. And one of the skeletons, called La Braña 2, was adorned with 24 pierced canine teeth from red deer, which had apparently been embroidered on a cloth that once covered the body.