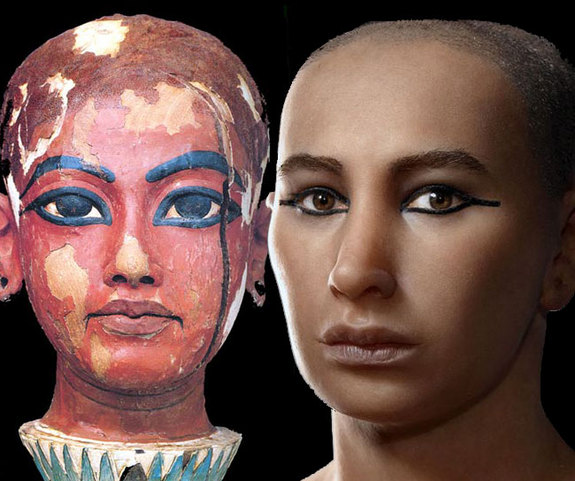

© Live Science

A personal genomics company in Switzerland says they've reconstructed a DNA profile of King Tutankhamen that shows the pharaoh's male lineage by watching the Discovery Channel, but researchers who worked to decode Tut's genome in the first place say the claim is "unscientific."

Swiss genomics company iGENEA has launched a Tutankhamen DNA project based on what they say are genetic markers that appeared on a computer screen during a Discovery Channel special on the famous

pharaoh's genetic lineage."Maybe they didn't know what they showed, but we got 16 markers from the Y chromosome from these pharaohs," Roman Schultz, the managing director of iGENEA, told LiveScience.

If the claims were true, it would put

King Tut in a genetic profile group shared by more than half of Western European men. That would make those men relatives - albeit distant ones - of the pharaoh.

But Carsten Pusch, a geneticist at Germany's University of Tubingen who was part of the team that

unraveled Tut's DNA from samples taken from his mummy and mummies of his family members, said that iGENEA's claims are "simply impossible." Pusch and his colleagues published part of their results, though not the Y-chromosome DNA, in the

Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) in 2010. The Y chromosome is the sex chromosome found only in males, and looking at the genes in this chromosome would show Tut's male lineage.

Comment: Actually, Jared Diamond is right, and agriculture is indeed the worst mistake in the history of the human race. Historical evidence also shows that it's not only temporal or that agriculture's benefits will be appreciated in the future. What's really been happening, that from the onset of farming human species have experienced a gradual degradation. We are on a fast track toward self-destruction on all levels.