American Exceptionalism Subsides

© Pew Research Center

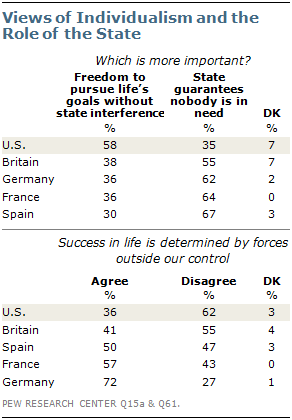

As has long been the case, American values differ from those of Western Europeans in many important ways. Most notably, Americans are more individualistic and are less supportive of a strong safety net than are the publics of Britain, France, Germany and Spain. Americans are also considerably more religious than Western Europeans, and are more socially conservative with respect to homosexuality.

Americans are somewhat more inclined than Western Europeans to say that it is sometimes necessary to use military force to maintain order in the world. Moreover, Americans more often than their Western European allies believe that obtaining UN approval before their country uses military force would make it too difficult to deal with an international threat. And Americans are less inclined than the Western Europeans, with the exception of the French, to help other nations.

These differences between Americans and Western Europeans echo findings from previous surveys conducted by the Pew Research Center. However, the current polling shows the American public is coming closer to Europeans in not seeing their culture as superior to that of other nations. Today, only about half of Americans believe their culture is superior to others, compared with six-in-ten in 2002. And the polling finds younger Americans less apt than their elders to hold American exceptionalist attitudes.

These are among the findings from a survey by the Pew Research Center's Global Attitudes Project, conducted in the U.S., Britain, France, Germany and Spain from March 21 to April 14 as part of the broader 23-nation poll in spring 2011.