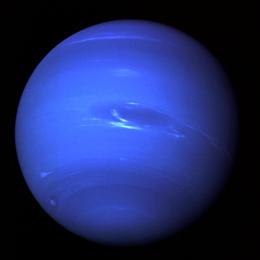

© Luis ReyMedusaceratops

Michael J. Ryan, Ph.D., a scientist at The Cleveland Museum of Natural History, has announced the discovery of a new horned dinosaur,

Medusaceratops lokii. Approximately 20 feet long and weighing more than 2 tons, the newly identified plant-eating dinosaur lived nearly 78 million years ago during the Late Cretaceous period in what is now Montana. Its identification marks the discovery of a new genus of horned dinosaur.

Ryan, curator and head of Vertebrate Paleontology at the Museum, published his findings on the new genus in the book,

New Perspectives on Horned Dinosaurs: The Royal Tyrrell Museum Ceratopsian Symposium, available from Indiana University Press. Ryan was the book's lead editor.

Medusaceratops belongs to the

Chasmosaurinae subfamily of the horned dinosaur family

Ceratopsidae. The other subfamily is

Centrosaurinae. The specimen is the first Campanian-aged chasmosaurine-ceratopsid found in Montana. It is also the oldest known

Chasmosaurine ceratopsid.

The new dinosaur was discovered in a bonebed on private land located along the Milk River in North Central Montana. Fossilized bones from the site were acquired by Canada Fossil, Inc., of Calgary, Alberta, in the mid-1990s.