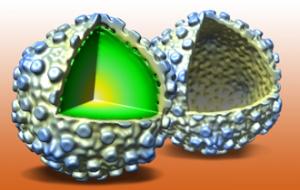

Pieces of a giant asteroid or comet that broke apart over Earth may have crashed off Australia about 1,500 years ago, says a scientist who has found evidence of the possible impact craters.

Satellite measurements of the Gulf of Carpentaria (see map) revealed tiny changes in sea level that are signs of impact craters on the seabed below, according to new research by marine geophysicist Dallas Abbott.

Based on the satellite data, one crater should be about 11 miles (18 kilometers) wide, while the other should be 7.4 miles (12 kilometers) wide.

For years Abbott, of Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, has argued that V-shaped sand dunes along the gulf coast are evidence of a tsunami triggered by an impact.

"These dunes are like arrows that point toward their source," Abbott said. In this case, the dunes converge on a single point in the gulf - the same spot where Abbott found the two sea-surface depressions.

The new work is the latest among several clues linking a major impact event to an episode of global cooling that affected crop harvests from A.D. 536 to 545, Abbott contends.

According to the theory, material thrown high into the atmosphere by the Carpentaria strike probably triggered the cooling, which has been pinpointed in tree-ring data from Asia and Europe.

What's more, around the same time the Roman Empire was falling apart in Europe, Aborigines in Australia may have witnessed and recorded the double impact, she said.

Comment: For an in-depth study, read Laura Knight-Jadczyk's review of New Light on the Black Death: The Cosmic Connection.