© Unknown

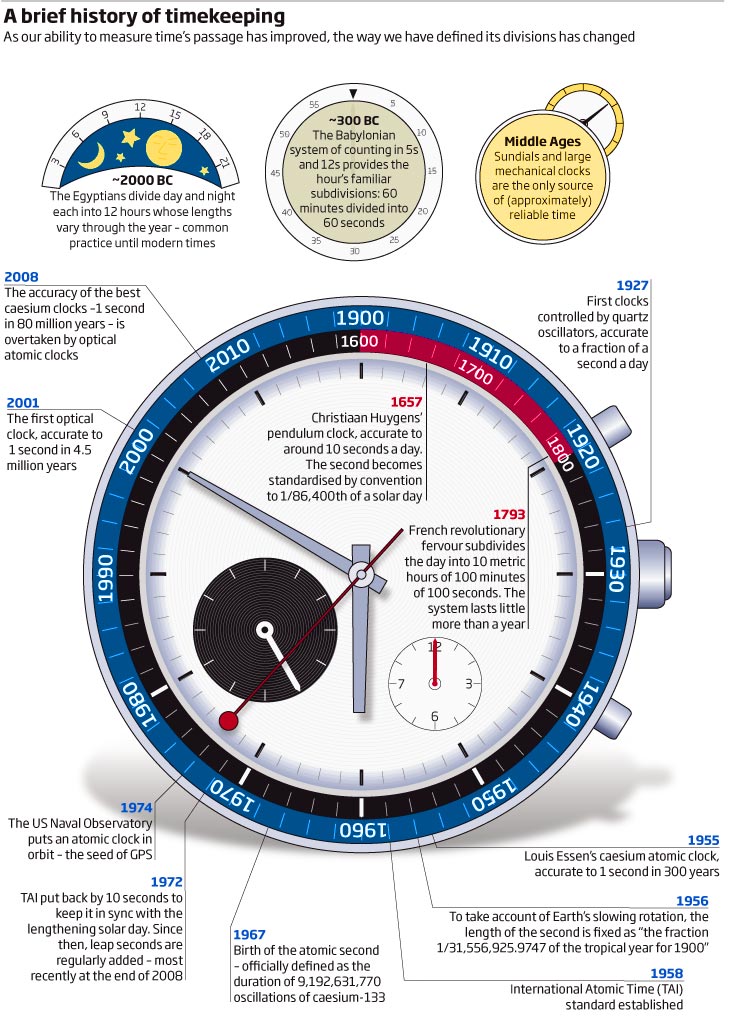

For those physicists and philosophers puzzled by nature's fourth dimension, Patrick Gill has a wry response. "Time," he says, "is what you measure in seconds."

For Gill, that is a statement of professional pride. He is what you might call Britain's top timekeeper. Within the windowless - and largely clockless - cream-brick confines of the UK's National Physical Laboratory (NPL), near London, Gill and his colleagues are busy developing the next, staggeringly accurate generation of atomic clocks. These tiny timepieces are the devices that ensure radio, television and mobile-phone transmissions stay in sync, prevent the internet from turning into a mess of missing data packets, make GPS accurate enough to navigate by, and safeguard electricity grids from blackout. They are, in short, the heartbeat of modern life.

These are momentous times for Gill and others like him in timekeeping laboratories around the world. A new generation of atomic tickers, known as optical clocks, have just wrested the record for accuracy from the ensembles of oscillating caesium atoms that held it for half a century. Soon, the new technology will be so refined that if such a clock had ticked away every second since the big bang 13.7 billion years ago, it would not yet have missed a beat. That is an awesome accomplishment - but it's also a problem. At this astonishing precision, we might have to rethink not only how we measure time, but also our concept of time.