© NASA

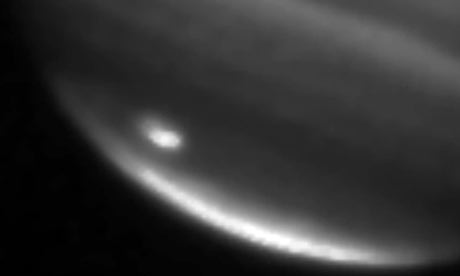

The Apollo 11 moon landing is not the only significant space anniversary that falls this week. It is also 15 years since

fragments of the Shoemaker-Levy 9 comet

smashed into Jupiter, in July 1994, giving astronomers a first-hand look at the devastation that follows such cosmic collisions.

With uncanny timing, a similar impact event seems to have happened again. On Sunday, an amateur astronomer named

Anthony Wesley observed a strange black

blob on the surface of Jupiter. When he alerted Nasa professionals, they

confirmed that it indeed appears to have been caused by another impact event.

The resulting debris cloud has been reported as covering an area with roughly the same diameter as the

Earth. Astronomers have told me today that the likely cause is the impact of a comet, or comet fragment, between 500m and 2km in diameter. It all raises a potentially terrifying question. What might have happened had such an object struck not Jupiter, but the Earth?

The good news is that the devastation would not have been quite as bad as it seems to have been on Jupiter. The mass of the gas giant is so much greater than that of the Earth, that when objects collide with it they do so at much faster speeds, releasing much more energy. So even though Jupiter is sporting an Earth-sized bruise, that doesn't mean that a similar impact would engulf the Earth entirely in debris.

It's also the case that such impact events are probably a lot more common on Jupiter than they are in our neck of the planetary woods. For a start, Jupiter is a much bigger target. And secondly, as Matthew Genge, of Imperial College, London, put it to me today, its vast gravity means it often;"soaks up" comets approaching the inner solar system from the Kuiper belt. This phenomenon, indeed, may actually have helped to make the Earth a more hospitable place for life -- though any benefits are double-edged, as Jupiter's gravity can also perturb the orbits of asteroids and fling them our way.

That, though, is where the good news ends. According to the UK's Near-Earth Object Taskforce

report, asteroids 700m in diameter strike the Earth every 10,000 to 100,000 years, and would devastate an area the size of Virginia if they hit land. An ocean impact would cause a hemisphere-wide tsunami. Objects on the 1km to 2km scale would cause wider destruction, and also affect the climate through a "nuclear winter" effect. Still larger objects could cause a mass extinction -- as did the 10km-plus object that landed at

Chicxulub, now in Mexico, 65 million years ago. Though some scientists dispute it, the prevailing consensus is that it's no coincidence that that's also the date for the Cretaceous-Tertiary

mass extinction, and the demise of the dinosaurs.

If you want an idea of the effects any given asteroid or comet might have, the University of Arizona has an online calculator

here. Just fill in your parameters and go.

The Jupiter impact should make it perfectly clear that, for all the fun that's been poked at Lembit Opik when he's raised the issue, near-Earth object defence is not a laughing matter. It's something the world needs to take extremely seriously -- as

Opik says again today. We need to think creatively about how we might divert an asteroid or comet that is found to be on collision course with Earth. Simply blowing it up, as Bruce Willis and Co. did in

Armageddon, will probably be the worst solution of all, creating a shower of fragments that would pepper us like Shoemaker-Levy 9 bombarded Jupiter. But there are other options worth trying, such as nudging it away from us with rockets, or even painting it to change its albedo, and hence its speed.

Technical fixes, however, will be only one element of a workable planetary defence plan. Professor Richard Crowther, who chairs the UN's working group on near-Earth objects, made an interesting point about this when I spoke to him this afternoon. If an asteroid is on collision course with, say, the UK, then nudging it away from Earth will first involve nudging it onto a collision course with other countries -- who might not like that prospect. We're going to need international agreement on the steps we would have to take to protect ourselves, as well as the technology to do so.

I find it interesting that people keep calling this impactor a comet when there was no sighting of it prior to the impact event. What this indicates to me is that the object was not changing its distance to the sun but was instead following a more orbital trajectory. If it had been moving from the outer solar system towards the sun (before meeting up with Jupiter) it should have exhibited a plasma tail since it would have been electrically discharging as it moved inward.

Does it make a difference whether it was an asteroid or comet? I would think so.