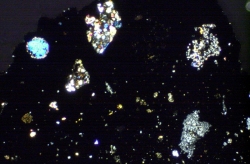

Parts of the Tagish Lake meteorite were found on a frozen lake near the Yukon border in January, 2000, after it fell to Earth in a spectacular blue-green fireball that was seen for hundreds of kilometres.

Researchers recovered parts of the still-frozen meteorite after an extensive search. Since then, scientists have repeatedly tried to unlock the clues that the rare 4.5 billion-year-old carbon and water rich meteorite has long been suspected to contain.

Now, a team at the University of Alberta has found some important material nestled inside the rock, formic acid - the key ingredient in bee stings, ant venom and stinging nettles.

U of A scientist Chris Herd says similar molecules on much, much earlier meteorites may have been instrumental in kick-starting life on Earth, making the meteorite the most important rock ever found on Earth.

"Four billion years ago, when the Earth had kind of cooled off from its initial hot state, and there was liquid water on the surface, we may have had an influx of meteorites like Tagish Lake [that] delivered the right mix of molecules to the Earth's surface," he said.

How exactly that mix might have turned into actual life is still a mystery, but Herd said the findings of formic acid on the meteorite may provide important clues.

"It's a type of molecule known as a carboxylic acid. So it's sort of like the shortest, smallest molecule in that group. The longer molecules in this same group are actually what life uses in building cell walls."

In 2001, U.S. exobiologist Sandra Pizzarello, who was studying some of the fragments from the Tagish meteorite at Arizona State University, said they contained almost no amino acids but did contain high concentrations of hydrocarbon molecules, along with a type of clay that forms in the presence of water.

In 2006, Mike Zolensky, a cosmic mineralogist at the NASA Space Centre in Texas, said tiny bubbles in the rock were organic globules where the universe's earliest life forms could have been able to live.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter