In 2015, he threatened deadly force to stop a fight between two more drunk men. One was armed with a hatchet. Another, with a wrench.

On another occasion, he drew his firearm to arrest a man hopping a backyard fence, fleeing the scene of a burglary.

None of these was remarkable in Richmond, a working-class city just east of San Francisco that's notorious for its drive-by shootings, break-ins, carjackings, and countless petty crimes.

When I asked Lande if he often had to unholster his gun — a standard-issue Glock 17 — he told me he'd done it so many times that "they all bleed into each other."

Luckily, he's never had to pull the trigger.

But things could easily have gone south. If a suspect had made a suspicious move or pulled something out of his pocket that looked like a gun — it happens more than you'd think — he would have had less than a quarter of a second to make the most awful decision of his life: whether to kill another human being.

Lande told me:

"You're in an incredibly inauspicious situation. The chance of making a good faith mistake is high."What that means is that if you're a cop, you've got to be confident that if a tragedy occurs — if a life is taken that should not have been taken — your chief, your city council, the powers that be will at least treat you fairly, hear you out, and ensure that justice is served.

But these days, a growing number of cops aren't so sure of that. Making the wrong decision is now a lot more likely to land you in prison, Lande explained. "It's not tenable for my family," he said. So in early 2022, he started thinking about quitting his dream job.

He was hardly alone.

A 2021 survey showed that police departments nationwide saw resignations jump by 18 percent — and retirements by 45 percent — over the previous year, with hiring decreasing by five percent. The Los Angeles Police Department has been losing 50 officers a month to retirement, more than the city can replace with recruits. Oakland lost about seven per month in 2021, with the number of officers sinking below the city's legally mandated minimum.

The list goes on: Chicago has lost more cops than it has in two decades. New Orleans is backfilling its shortfall of officers with civilians. New York is losing more police officers than it has since such figures began being recorded. Minneapolis and Baltimore have similar stories. St. Louis — one of the most dangerous cities in America — has lost so many cops that there's a seven-foot-tall, 10-foot-wide pile of uniforms from outgoing officers at police headquarters called "Mount Exodus."

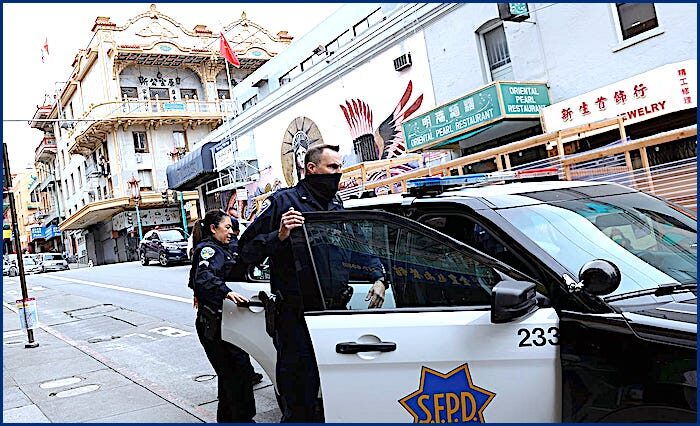

And in San Francisco, just across the bay from Richmond, the police department has seen 50 officers out of a force of fewer than 2,000 take off for smaller, suburban departments, according to Lieutenant Tracy McCray, the head of the city's police union.

"That was a lot of talent for us. They were great, bright new cops. A couple of them were born and raised in the city. All of their roots they had here. They just up and left."These were the kind of officers that advocates for reform say they want more of: cops from the communities they police, black cops, Latino cops.

A big part of what's prompting police to leave America's big cities is the perception the public has turned against them. A 2020 poll showed that only seven percent of police officers would advise their kids to go into law enforcement. Eighty-three percent of those who wouldn't recommend it cited "lack of respect for the profession."

McCray, who is black, said:

"Suddenly, everyone is telling us how to do our jobs. They're saying we're biased, racist, only want to hurt black and brown communities. These officers worked in these communities, were invested in these communities. Suddenly, people who don't know us are saying you're this, you're that."The shift in police officers' perception of how they're viewed by the public happened gradually — starting with the first Black Lives Matter protests of 2013, after the shooting death of Travyon Martin and the acquittal of the man who killed him, George Zimmerman. There were more BLM demonstrations: in 2014, following the deaths of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Eric Garner in New York. Then came the 2015-2016 Democratic presidential primaries, in which BLM played a prominent role.

And then, in late May 2020, George Floyd, a black man, was killed by a white police officer, Derek Chauvin, and it was caught on video. The incident ignited protests across the country — a "racial reckoning" — and, soon after, reform.

In some cities, including Portland, Oregon and Columbus, Ohio, local governments set up police review boards with the power to subpoena police records and oversee day-to-day policing. States including Illinois, Minnesota, and Oregon tightened use-of-force standards. New Mexico and Minnesota required officers to intervene if another officer was using what might be deemed unreasonable physical force.

It became popular — even fashionable — for politicians in progressive circles to flaunt their anti-police credentials. In Minneapolis, where George Floyd was killed, the city council resolved to "begin the process of ending the Minneapolis Police Department." (They reversed course after crime surged.) In New York, after winning the Democratic congressional primary, now-Rep. Jamaal Bowman tweeted:

"Police officers have sworn to protect and serve the institution of white supremacy."A month later, the ACLU tweeted:

"Policing is rotten to its core" and "has always been a racist institution in the United States."In Portland, Kristina Narayan — the legislative director for Tina Kotek, who was then Oregon's Speaker of the House and is now the governor — was arrested while participating in anti-police protests at which Molotov cocktails were thrown at the cops.

All of this revealed a disconnect between progressives and much of the rest of the country, including many Democrats: A 2020 New York Times poll showed that 63% of registered voters opposed cutting police budgets while 55% of Biden supporters favored it.

Peter Moskos, a former Baltimore police officer who teaches at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York, said:

"When I was a cop, we were afraid we might mess up and get in trouble. But you had to do something wrong. Now cops are getting in trouble for doing exactly what they're supposed to do."Brian Lande, a Richmond police officer, referred to a 2019 California law that further limits when cops can use force — and more broadly, to the shift in thinking among Democratic elites:

"The rules of the game changed. Let's say you see a guy, he's just robbed a bank, he's got a gun, he's running now into the preschool. Once upon a time, that would have been enough to justify using force. Now you've got to be confident that a crime is 'imminent' — and sometimes you've only got milliseconds to figure that out. If you get it wrong, and if the skin color of the cop and the victim suit the narrative that cops are propping up the institution of white supremacy and wantonly snuffing out black bodies, you could be prosecuted as a murderer."McCray told me:

"Other people who don't live in your community, but who are speaking on behalf of your community, don't know what the fuck they're talking about. Black Lives Matter was talking about putting ambassadors on the street — where they at?"Referring to one of San Francisco's most violent neighborhoods, she added:

"Haven't seen one damn member of Black Lives Matter patrolling the Bayview making sure police aren't 'hunting and killing black people. If you're a cop, you're like, 'Ok, well, I guess I'm not going to put myself in situations where that's likely to occur.' So I'm not going to go make traffic stops in places and of people that I think might likely be carrying firearms, because I don't want to have to get that decision right. That's too hard."In Richmond, the politicians were signaling loud and clear: We don't like cops.

After the riots in Ferguson, and especially after the murder of George Floyd, the Richmond City Council cut the police budget, forcing hiring freezes. Council members also threatened to slash officers' salaries by 20 percent.

By last spring, the Richmond Police Department had lost so many officers that those who remained were forced to work overtime 40 to 60 hours per month. That requirement came on top of being forced to work back-to-back shifts when unexpected vacancies opened up. Investigations and traffic enforcement more or less stopped. Burnt-out officers were just doing patrols — driving around passively, waiting for something to happen.

When Lande tried to recruit new officers, cops told him they preferred to go somewhere with a friendlier local government, where they wouldn't have to fear getting laid off or having their salaries and benefits reduced. Many went to Napa and Sonoma Counties — wine country.

Last September, Lande followed suit and left Richmond. Lande told me:

"I felt very conflicted about it. Residents of Richmond are disproportionately poorer, disproportionately victims of violent crimes."Lande and I had known each other since our graduate school days, studying sociology at Berkeley. He's one of the most thoughtful and educated — and experienced — cops in the Bay Area. He has published academic papers on how to train the police to interact more effectively with the public. He had studied this question — police-community relations — while on a stint at the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, which is part of the Pentagon.

But research hadn't been enough for Lande. "As an academic sociologist, I learned quickly that my ability to make a difference was pretty limited," he said. As a police officer, he went on, "I could make a difference in people's lives — and I wasn't bad at it."

He loved his job in Richmond. But the calculus of policing had changed.

In August, as Lande was preparing to leave, Richmond saw four murders in the span of a week. In the same time period, Oakland, to the south, experienced five murders in three days — and the following month, three homicides in a single hour.

Lande transferred to Kensington, a 15-minute drive away.

Kensington is filled with California craftsman-style bungalows, mid-century ranch houses and Spanish-style villas with Priuses and Teslas out front, and decks with gorgeous views of the San Francisco Bay out back. Black Lives Matters signs are everywhere, reflecting Kensington residents' solidarity with working-class black people in cities like Richmond — even as Richmond has become less safe as a result of the changes that movement has ushered in.

Life is good: Officer Lande is now Sergeant Lande. His job involves far fewer risks. Much of his day is filled with administrative work at the station. When he goes out on patrol, he mostly writes parking tickets.

But he is not optimistic.

"An enormous amount of damage has been done. Instead of seeing real investment in policing, like what we see in Europe, we've seen a massive disinvestment."In August 2022, President Biden announced his Safer America Plan in response to rising crime. Among other things, it includes plans to hire 100,000 more police officers. That upset the ACLU, which disparaged the plan as "more criminalization and incarceration," and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, which asserted — without providing evidence — that adding police officers would only victimize black people.

Peter Moskos, the former Baltimore police officer now teaching at John Jay College, was mystified by progressives who insist that the single greatest threat faced by black Americans is systemic racism. Moskos, who has called for legalizing drugs in response to the drug war's ineffectiveness and its disproportionate impact on young black men, said:

"Congratulations! You've increased the black murder rate. You're giving blacks worse policing through this transfer of cops — and doing it smugly in the name of racial justice."

About the Author:

Leighton Woodhouse is a journalist and documentary filmmaker in Oakland.

A minority of your fellow officers are the epitome of bullys.

Just like us here in civvy street, you are not immune to the acts of a minority of siht heads